First Nations: Life on the Prairies

~14,000 years ago to A.D. 1810

According to the Indigenous worldview, it matters less what happened in history than the stories shared today. Let’s explore this more.

Living History

At ENMAX Park during the Calgary Stampede, five First Nations establish Elbow River Camp (formerly Indian Village).

In a large circle, tipis illustrated with dream-like images are erected and for 10 days the park comes alive with drumming, singing, bright colours, and learning the stories and memories of this land.

Calgary is bordered on its immediate southwestern edge by Tsuut’ina Nation. The Tsuut’ina are connected to the Dene Nation up north through language (Athabaskan), culture and territory. The two nations separated in the early 1700s, a moment retold in oral histories.

Tsuut’ina means “many people” or “beaver people”, and they are “a small piece of the sacred circle. We respect all spirits of the land and how the elements of water, air and fire are a part of the circle we call Natural law”. (https://tsuutina.com/).

Further west lies Stoney Nakoda Nation (Îyârhe Nakoda). The name “stoney” is from early Europeans, who are thought to have observed a process of cooking with stones. Historically, the Nakoda peoples were known as Wapamakthe, “head hunters”, but today are known as Iyethka, “the pure people”, with Îyârhe meaning “mountain” and Nakoda meaning “friend” or “ally”.

There are three bands (Bearspaw, Chiniki and Goodstoney) on six reserves located along the foothills. They speak the Stoney Nakoda language, a branch of the Sioux-Assiniboine language family. The Nakoda separated from the Assiniboine in Saskatchewan in the mid-1700s.

About an hour’s drive east of downtown Calgary is Siksiká (“black foot”) Nation, part of the Blackfoot Confederacy, Siksikai’tsitapi (“children of the plains”).

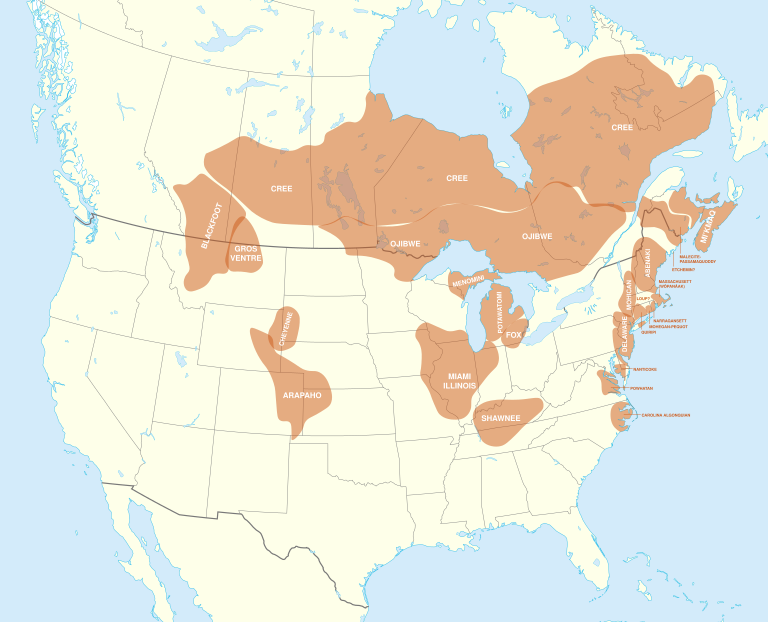

When Europeans arrived on the east coast of North America, competition for resources between First Nations increased. This caused the Blackfoot to migrate from the Canadian Shield around the Great Lakes to the prairies. They inhabited territory that stretched from the North Saskatchewan River in Alberta and Saskatchewan to the Yellowstone River across the U.S. border in Montana, from the Rockies to Regina.

The Blackfoot are linked through historical ties, cultural memories and Siksikai’powahsini, the Blackfoot language, a branch of Algonquian.

To the south of Lethbridge is Kainai Nation. Kainai comes from the word káína, which translates to “many chief people”. They are also called the Blood Tribe because, in the past, Cree-speaking foes called them Mihkowiyiniw (“stained with blood”).

The Kainai are part of the Blackfoot language group and Confederacy. The Kainai News was one of Canada’s first Indigenous newspapers, first published in 1968, and was fundamental to the advocacy of Indigenous interests. In 1960, the Kainai invited the National Film Board of Canada to record a sacred Sun Dance in the documentary Circle of the Sun.

Further west of Kainai is Pi’ikanni Nation, also referred to as the Northern Piikani (Aapátohsipikáni) or the Peigan Nation. They are members of the Blackfoot Confederacy and have a long history across the U.S. border with the Southern Piikani (Aamsskáápipikani), based at Blackfeet Indian Reservation, Montana.

Piikani is an adaptation of the word apiku’ni, meaning “badly tanned or scabby robe”. The reference to scabby, i.e., meanness, may be a reference to the military prowess of the Blackfoot, who protected their borders from the Cree to the east and from the tribes of Snake Country to the south.

Calgary is also located in Métis Nation of Alberta District 5 – Nose Hill and District 6 – Elbow Region. And with that we turn to their history, which is inextricably linked with the arrival of Europeans to the shores of the Americas.

Europeans

The presence of Europeans in our region begins on the rivers. French fur traders – les voyageurs – made forays into the Great Plains to trade manufactured goods for furs with Indigenous peoples.

Meanwhile, the English were establishing trading posts on the shores of Hudson Bay.

The Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) was granted a monopoly in 1670 for England’s beaver fur trade in the Hudson Bay’s watershed. The watershed was called Rupert’s Land, named after King Charles II’s cousin and the company’s first governor, Prince Rupert of the Rhine.

When the French started competing directly with HBC, by building forts on Lake Winnipeg in 1741, and when the British Parliament offered a prize for the discovery of the Northwest Passage to the Pacific Ocean in 1745, HBC decided to go west.

Anthony Henday was a HBC labourer at York Factory, near today’s town of Churchill, MB. He volunteered for the mission to develop trade relations with Indigenous peoples.

In the autumn of 1754, Henday and his Cree guides, led by Attickasish, travelled along the Saskatchewan River and into the Battle River area, arriving near Innisfail, southeast of today’s location of Red Deer. They wintered in the area next to a large Blackfoot camp, perhaps near today’s Rocky Mountain House, meaning he may have been the first European to see the Canadian Rocky Mountains (since the voyageurs didn’t keep journals, historians can only guess who was truly first).

In spring, the party headed back to York Factory, having traded goods for furs. Henday returned to the Alberta area in 1759, but the vast distances and antipathy between the Cree and Blackfoot meant it was difficult to sustain the whole trade route. His effort and tenacity expanded knowledge of Canada’s first highway system: the rivers and their portages. Edmonton’s ring road is named in his honour.

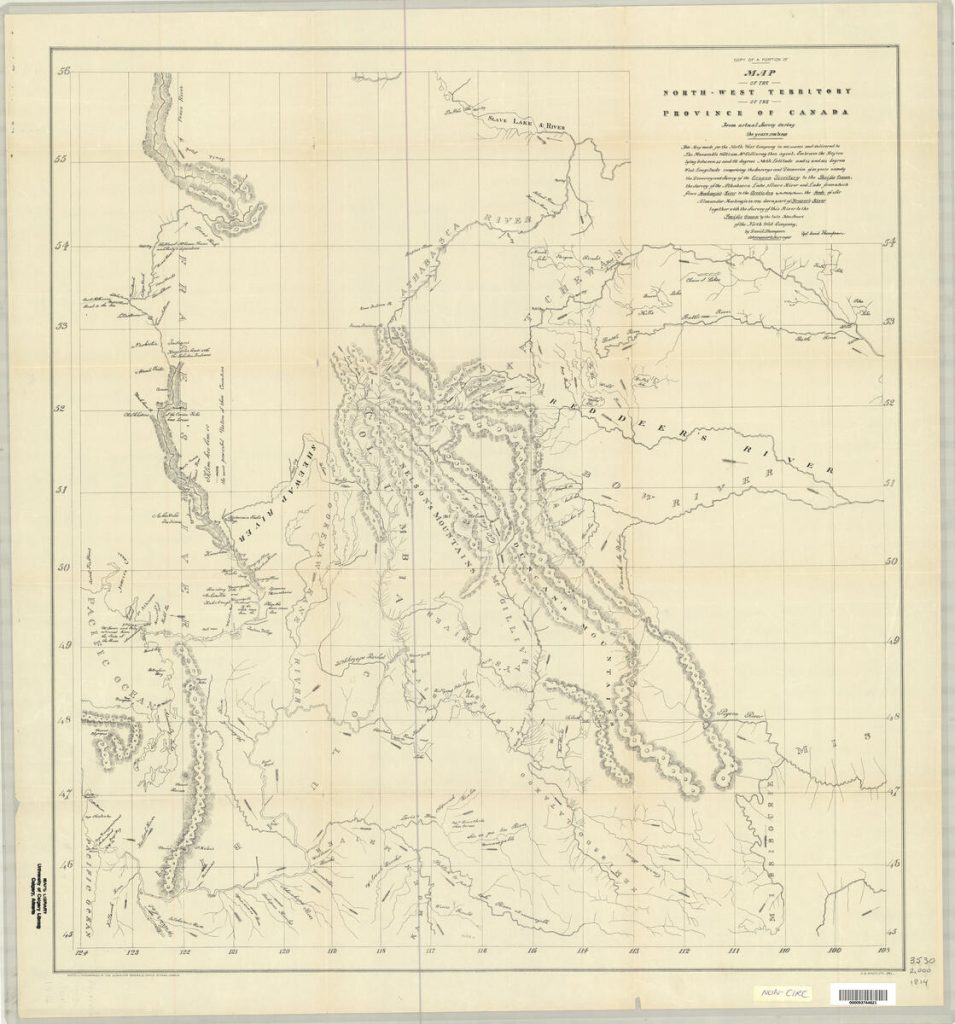

In 1798, David Thompson was sent by the North West Company to establish a trading fort at Red Deer Lake, today’s Lac La Biche, AB. The North West Company (NWC) was based out of Montreal and competed with HBC for the fur trade in Rupert’s Land after the British overtook New France in 1763.

Competition was fierce at times, with dual forts established at Fort George/Buckingham House in 1792 and Rocky Mountain House/Acton House in 1799. From Fort George, Thompson explored the Rocky Mountains.

In his journals circa 1800, Thompson reported on the view from Nose Hill: “To the westward, hills and rocks rose to our view covered with snow, here rising, there subsiding, but their tops nearly of an equal height everywhere. Never before did I behold so just, so perfect a resemblance to the waves of the ocean in the wintry storm”.

Nose Hill probably gets its name from the shape of the hill as seen from a distance. This observation pales in comparison to Blackfoot legend, which tells a warning tale about infidelity. The culprit was condemned on the Hill and punished by having her nose removed and left on the hill, afterwards known as Nose Hill. So behave yourselves!

In 1806, NWC charged Thompson with seeking a trade route to the Pacific Northwest in response to the United States backing Lewis and Clark’s expedition to the same area. Leaving from Rocky Mountain House, he went on to establish Kootenae House in 1807. From there, Europeans could trade with the Ktunaxa for fur. It also was a launching point to survey the Columbia River.

Upon hearing of American plans for the Pacific Coast in 1810, Thompson was ordered back to the area to find a route to the mouth of the Columbia River. En route, Thompson was unable to come to terms with the Piikani at Howse Pass in today’s Banff National Park, who did not want Thompson trading guns with the Ktunaxa. He was forced to travel outside Blackfoot territory, entering the Rockies through Athabasca Pass in today’s Jasper National Park.

His expeditions brought the fur trade to our region and he was able to strengthen trade relationships between Indigenous peoples on either side of the Rocky Mountains.

Thompson died poor and unrecognized, that is, until Joseph Tyrrell remarked at the accuracy of the maps he was using for the mountains. He was so impressed he wrote about Thompson’s feat. Both passes are now National Historic Sites and David Thompson, with the knowledge and assistance of Indigenous peoples, is remembered as the Great Mapmaker of Canada.

Métis

As Europeans progressed westward of Lake Superior, they interacted with Indigenous peoples in the fur trade. Over the decades, mixed families resulted. They are the founders of the Métis.

Those working for the fur trading companies built and maintained forts as well as plied the rivers on canoes. Those who built Rocky Mountain House were Métis. Others were guides, interpreters, clerks, negotiators and provisioners.

Some Métis became free traders and hunters, known as Freeman bands. They were independent traders who left the fur trade’s river highways and entered the prairies to trade goods with the Blackfoot for pemmican, the food that fueled the fur trade.

Peter Fidler was one such company man. Born in Derbyshire, England, he joined HBC in London and eventually arrived at York Factory.

Fidler was part of HBC’s surveying of the interior. He reached the Rocky Mountains in 1792, becoming the first to survey the Battle, Red Deer, Bow, and Highwood Rivers. He was perhaps the first European to meet with the Ktunaxa. He developed maps for HBC with information from Siksiká chief Aka-Omahkayii (“Old Swan”).

In 1799, he established Greenwich House at Lac La Biche. He also became involved in several hostile interactions with the North West Company in the region. Back at York Factor, Fidler married Mary (Methwewin) Mackagonne, a Cree woman, and together they had 14 children.

From the interactions between First Nations, Métis and fur traders, our region began to experience rapid changes, which we’ll explore next month.

– Anthony Imbrogno is a volunteer with The Calgary Heritage Initiative Society/Heritage Inspires YYC

– All copyright images cannot be shared without prior permission

Addendum

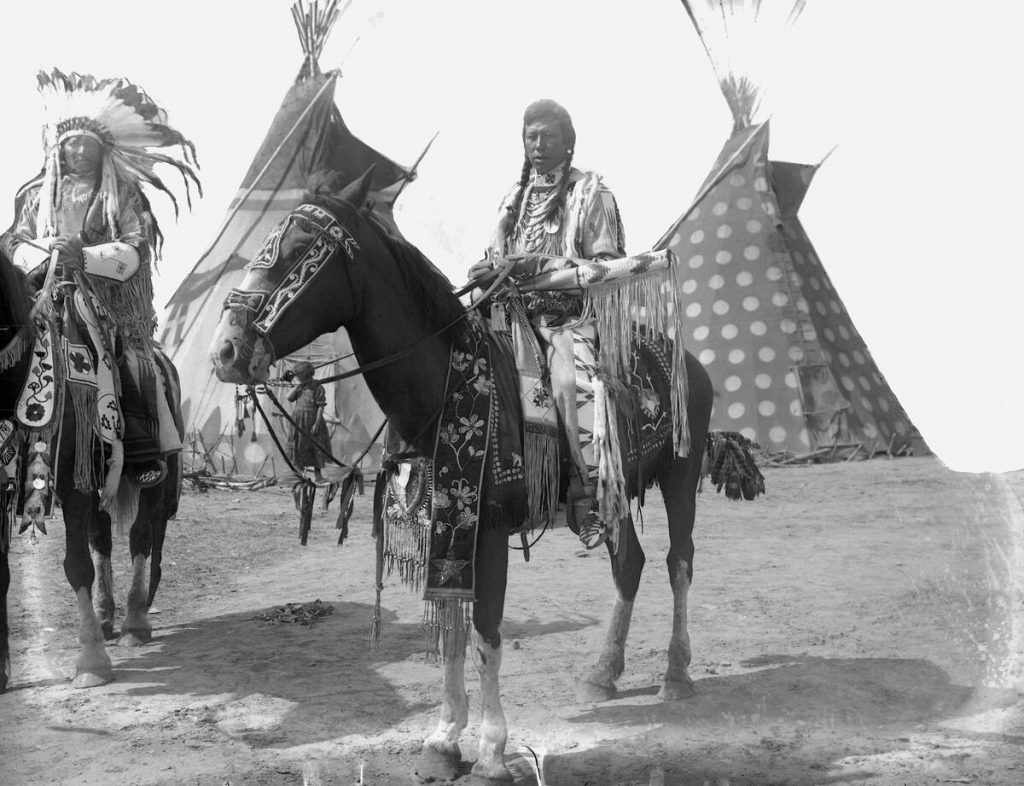

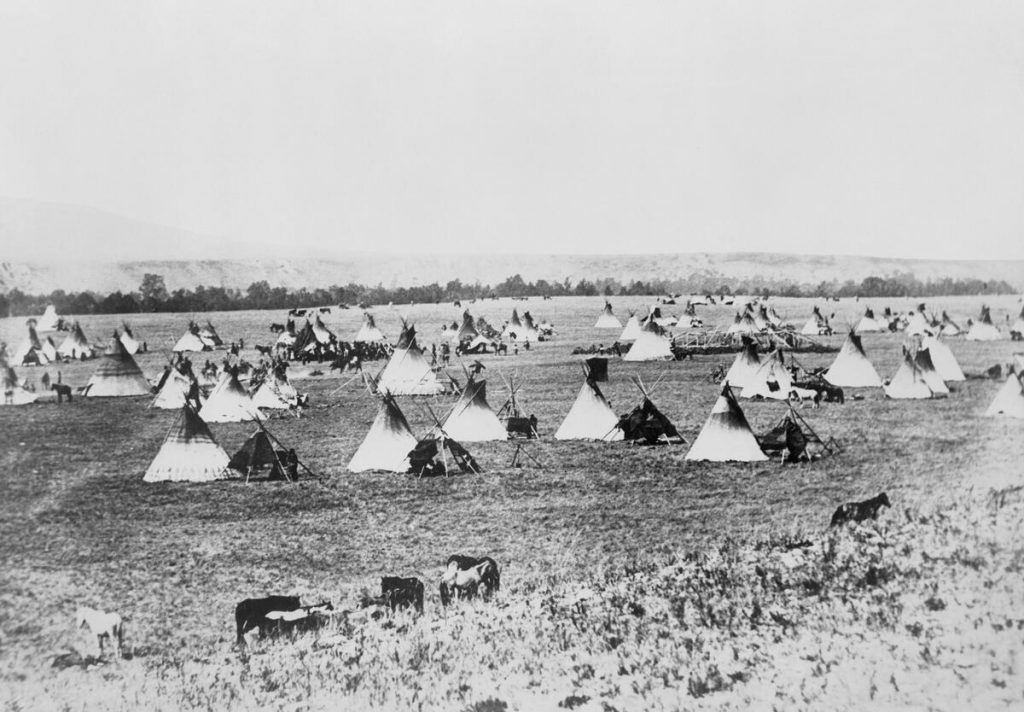

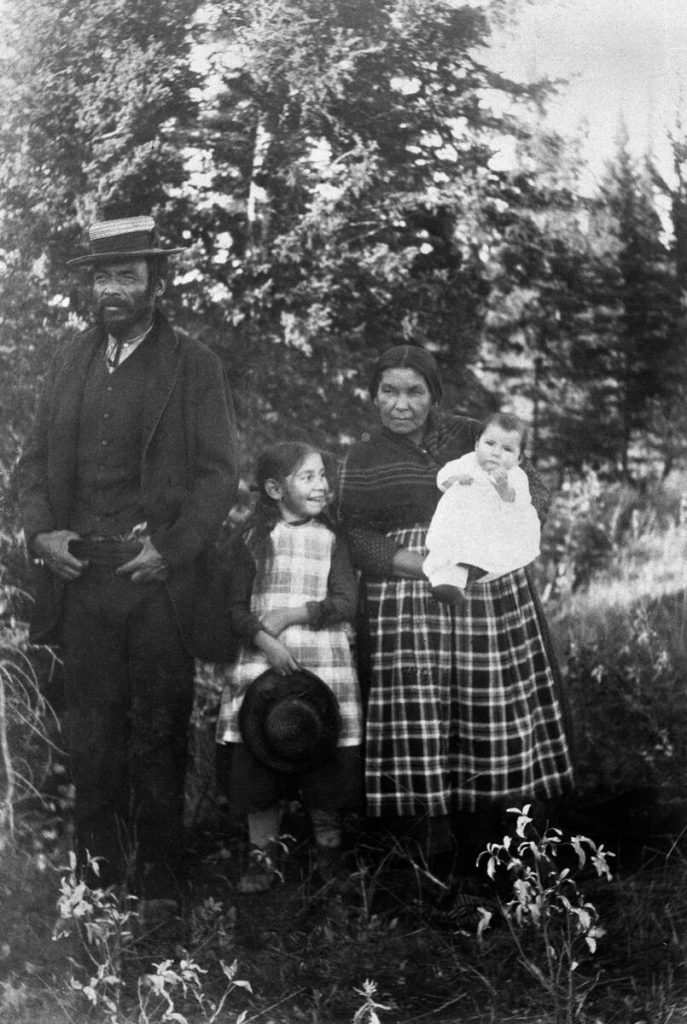

The following photos were taken during a trip to Montana:

Where to See This Era

Hot Springs

- Banff Upper Hot Springs, 1 Mountain Ave, Banff, AB T1L 1K2

- Cave and Basin National Historic Site, 311 Cave Ave, Banff, AB T1L 1K2

- Radium Hot Springs, 5420 BC-93, Radium Hot Springs, BC V0A 1M0

Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park Visitor Centre, Range Rd 130A, Aden, AB T0K 0A0

Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump UNESCO Heritage Site, 275068 Secondary Highway 785, Fort MacLeod, AB

Nose Hill Park, 6465 14 St NW, Calgary, AB T3K 2P6

Royal Alberta Museum, 9810 103a Ave NW, Edmonton, AB T5J 0G2

ENMAX Park (Indian Village/Elbow River Camp during the Calgary Stampede), 801 MacDonald Ave SE, Calgary, AB T2G 4M3

Tsuu T’ina Cultural Museum, 62 Old Agency Rd, Priddis, AB T0L 1W0

Chiniki Cultural Centre, TransCanada Highway & Morley Road (Exit 131), Morley, AB T0L 1N0

Buffalo Nations Museum, 1 Birch Ave, Banff, AB T1L 1A8

Fort George and Buckingham House Provincial Historic Site, 6015 Township Rd 565, Elk Point, AB T0A 1A0

Rocky Mountain House National Historic Site, Site 127 Comp 6 RR4, Rocky Mountain House, AB T4T 2A4

Kootenae House National Historic Site, Westside Road, Athalmer, BC V0A 1A0

Lac La Biche Mission National Historic Site and Museum, 67453 Mission Rd, Lac la Biche, AB T0A 2C0

Videos

Circle of the Sun: https://www.nfb.ca/film/circle-of-the-sun/

Les Voyageurs: https://www.nfb.ca/film/voyageurs/

David Thompson, The Great Mapmaker: https://www.nfb.ca/film/david_thompson_the_great_mapmaker/

Further Reading

Liz Bryan, Stone by Stone: Exploring Ancient Sites on the Canadian Plains (Expanded Edition), 2015, Heritage House Publishing Company.

Grant MacEwan, Buffalo: Sacred and Sacrificed, 1995, Alberta Sport, Recreation, Parks & Wildlife Foundation.

Uncovering Human History: Archaeology and Calgary Parks, 2019, The City of Calgary.

Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park

For a map of First Nations and Métis areas in Alberta, see https://www.alberta.ca/map-of-first-nations-reserves-and-metis-settlements

Leave a Reply