Welcome! The Calgary Heritage Initiative presents a series of articles throughout 2025 commemorating the 150th anniversary of the construction of Fort Calgary at the confluence of the Bow and Elbow Rivers, an important meeting place for people for millennia. Each month we’ll present one era in Calgary’s history.

Sign up to CHI’s newsletter and join us to explore the history and heritage of our region.

Treaty 7 and Cow Town

1875 to 1885

The North West Mounted Police arrived in southern Alberta in 1874 to handle some serious problems, particularly the threat of lawlessness.

Thanks to their efforts and to those who sought peace, the Canadian West avoided the ignominy of the American West’s violence and harshness. Nevertheless, serious issues were about to confront all of the prairies’ inhabitants.

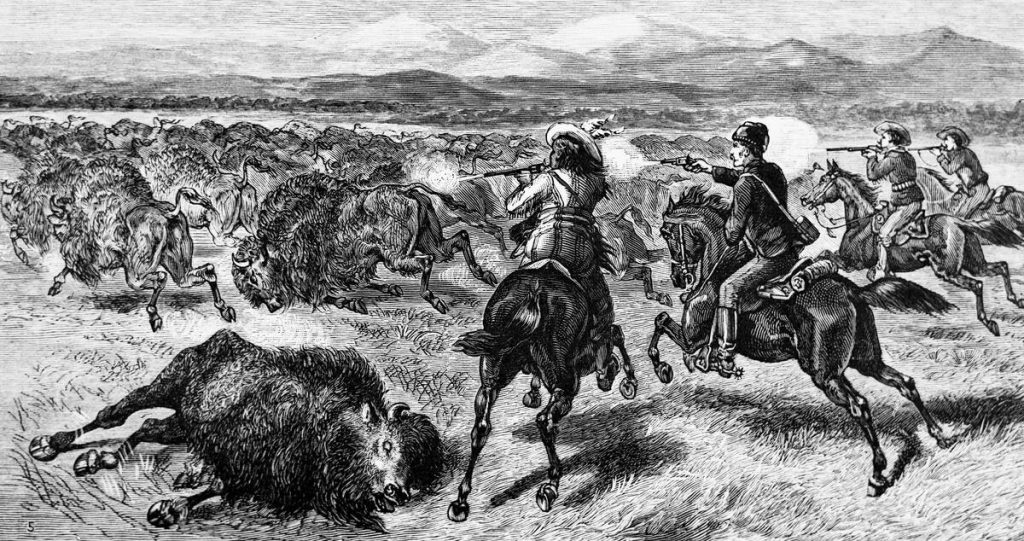

For one, smallpox was running rampant again throughout the region in 1870. Another problem was the buffalo approaching extinction due to the incessant hunting of herds all across the Great Plains.

Hunting was made easier by guns and horses. More settlements and the demands of trade added even more pressure. In 1874, 250,000 buffalo hides were marketed at Fort Macleod. In 1877, the number collapsed to 30,000 and by 1879 only 5700 hides were available.

The difficulty of hunting a dwindling population of buffalo caused tensions to escalate amongst Indigenous peoples. They had relied on the seasonal round for thousands of years. The buffalo were the keystone species not only of prairie ecology but also of the region’s society and relations between peoples.

War

Past disputes between Blackfoot and Cree over trade routes and trading privileges evolved into open warfare.

Cree Chief Maskepetoon was a renowned warrior in his early life. Upon contact with Rev. Rundle in the 1840s, he became a proponent of peace, and was eventually baptized. In 1869, open hostility broke out between Cree and Blackfoot. When Maskepetoon entered a Blackfoot camp unarmed to negotiate peace, he was killed by Chief Big Swan. The Cree vowed reprisal.

Tensions were high on the prairies. Rev. John MacDougall, a friend of Maskepetoon, reported that “the strain was continuous, disease and death and danger constant”.

Among the Kainai, Chief Red Crow assumed the leadership after his father died of smallpox in 1869. The band was also experiencing the terrible effects of the whisky trade. It’s reported that Red Crow killed his brother during a drinking bout, two others died in a fight, and Red Crow’s wife died because of a stray bullet. The shock of this incident helped the Blood to accept and welcome the NWMP into the area to combat the illegal trade.

The now open conflict between Cree and Blackfoot culminated in the The Battle of Belly River, which occurred in October 1870 along what is today called the Oldman River in Lethbridge.

The Cree had proceeded south to take advantage of the Blackfoot inflicted with smallpox. A group of Cree attacked a Blackfoot camp, but the Blackfoot received reinforcements the next day. According to guide Jerry Potts, between 200-300 Cree and 40 Blackfoot died in the battle. The event is commemorated at Indian Battle Park in Lethbridge.

Peace

The ferocity of the battle, combined with the weakening of all Indigenous peoples due to disease, alcohol and disappearing buffalo, led to negotiations. Peace was attempted in 1871, when Chief Many Swans joined other leaders on Nose Hill to discuss and ceremonialize an agreement over territory. To seal the deal, Blackfoot Chief Crowfoot ritually adopted Cree Chief Poundmaker in 1873.

After the arrival of the NWMP in 1874, Chief Red Crow met with Col. Macleod, as did Chief Crowfoot. Crowfoot wanted to discuss the relationship between peoples, and he and Macleod grew to respect each other. Crowfoot wanted Macleod and the government he represented to respect Blackfoot rights while Macleod wanted Crowfoot and his people to maintain friendly relations with the NWMP and the homesteaders.

Their burgeoning relationship would prove fortuitous since problems in Montana Territory were getting worse. In 1876 during the Great Sioux War, Chief Sitting Bull approached Crowfoot and offered an alliance of warriors to take on the U.S. Army and NWMP. Instead, Crowfoot honoured his agreement with Macleod and refused Sitting Bull’s offer.

The Great Sioux War proceeded between the United States and the Sioux who resisted the arrival of railway engineers, surveyors, miners, and the rest who followed into the Black Hills and beyond. The Indigenous peoples who refused to move to the Sioux Reservation, led by Chiefs Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse and Gall, were considered hostile.

At the Battle of the Little Big Horn/Greasy Grass, the U.S. Army under the command of Lt.-Colonel George A. Custer was roundly defeated by the combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho. It became known as Custer’s Last Stand.

Grave of Colonel Keogh, Custer battlefield, Little Big Horn, MT, 1877 (Glenbow Library and Archives Collection)

The Battle resulted in Congress agreeing to expand the U.S. Army, which led to the eventual surrender of the remaining Sioux. Some, including Sitting Bull, fled to Canada in 1877. Chief Crowfoot and the NWMP offered them refuge, but little food from the remaining buffalo herds and the Canadian government’s refusal to officially recognize the Sioux led Sitting Bull to return to Montana.

Sitting Bull is also famous for his role in Wild Westing, which refers to the performance of Indigenous peoples in travelling showcases, such as Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. Sitting Bull is best remembered for his perseverance and dedication to his people at the twilight of their seasonal round.

Treaty 7

The arrival of Chief Sitting Bull to Canada, and thus the potential for the American conflict to spread northward, led Canadian authorities to offer formal treaty negotiations with the Indigenous peoples of the region. In 1877, David Laird, Lt.-Governor of the North West Territories, invited the Indigenous peoples south of the Red Deer River – Siksiká, Piikani, Stoney, Kainai and Tsuut’ina – to negotiate Treaty 7.

The Numbered Treaty program was used by the Canadian government throughout the 1870s to negotiate between Indigenous sovereignty and the Canadian Crown’s newfound authority. More specifically, it enabled the construction of a railway across the continent. The program led to the creation of reserves where Indigenous peoples could secure their livelihoods and continue practicing their traditions all while adapting to the region’s development.

The meeting place for the negotiations was the first point of contention. The Kainai and Piikani preferred Fort Macleod while Crowfoot insisted on Blackfoot Crossing, away from the authority of the NWMP.

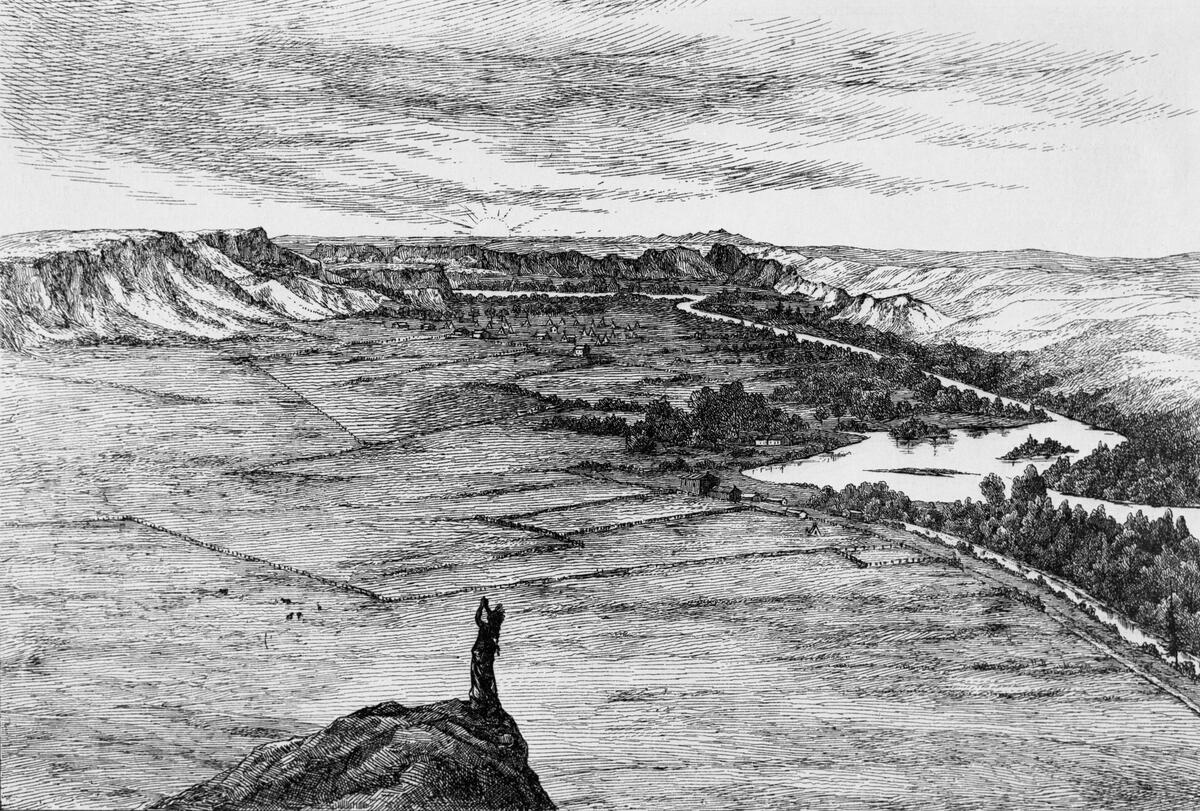

Blackfoot Crossing is today located on Siksiká land near Cluny, AB. It was the location of a ford across the Bow River for buffalo herds and is a gathering place for Indigenous peoples. Crowfoot’s location was accepted.

View of Blackfoot Crossing, Marquess of Lorne sketching, 1881 (Glenbow Library and Archives Collection). Library and Archives Canada holds the original negatives.

Negotiations began on 16 September 1877. Crowfoot led the discussions for four days. Rev. McDougall, who had taken part in Treaty 6 negotiations, was also present as interlocutor and trusted intermediary. He had a strong relationship with Chief Chiniquay of the Stoney, who supported McDougall starting a mission at Mînî Thnî (Morleyville) in 1873.

When the other Chiefs arrived, Crowfoot delivered an account of the talks to them. Canadian settlement was to be exchanged for Indigenous peoples’ land rights as well as farming support, cattle, food, ammunition and annuities.

It was reported that Chief Mas-gwa-ah-sid (“Bear’s Paw”) was the first to accept the Treaty, whereas the others discussed it through the night. On September 22nd, the Treaty was agreed and signed in front of 5000 people. Today, Blackfoot Crossing is a National Historic Site and the location of a Blackfoot museum and cultural centre.

Crowfoot remarked at the signing,

“The plains are large and wide. We are the children of the plains, it is our home, and the buffalo has been our food always…If the Police had not come to the country, where would we be all now? Bad men and whiskey were killing us so fast that very few, indeed, of us would have been left to-day. The Police have protected us as the feathers of the bird protect it from the frosts of winter. I wish them all good, and trust that all our hearts will increase in goodness from this time forward. I am satisfied. I will sign the treaty”.

Attention now turned to the future.

Settlement was increasing rapidly in anticipation of the railway at the same time as the buffalo stopped appearing on the plains. It became evident quickly after signing that both parties to the Treaty 7 negotiations were operating on assumptions that were not addressed, and the interplay between them reverberates to this day.

The most broad and significant issue concerned the notion of property. To the Indigenous peoples, the land and buffalo did not belong to anyone, they were created by Náápi (“Old Man”) and could not be kept by anyone. As well, Indigenous peoples had travelled all throughout the region as part of the seasonal round, so the concept of a parcel of land, a reserve, was unfamiliar.

Furthermore, the smaller size of the reserves compared to traditional territories was not made clear. The location of reserves was also not specified sufficiently, with Indigenous lands ending up being of poorer quality. Another issue was the financial compensation offered in the Treaty became a pittance over time. Coupled with the decreasing availability of buffalo, the reserve system did not live up to expectations.

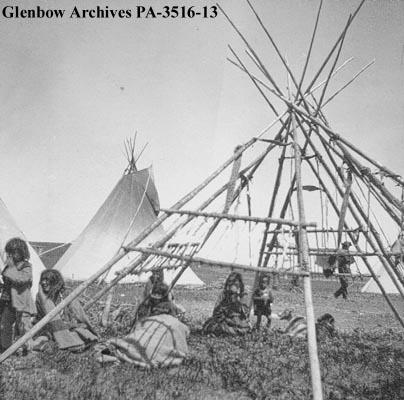

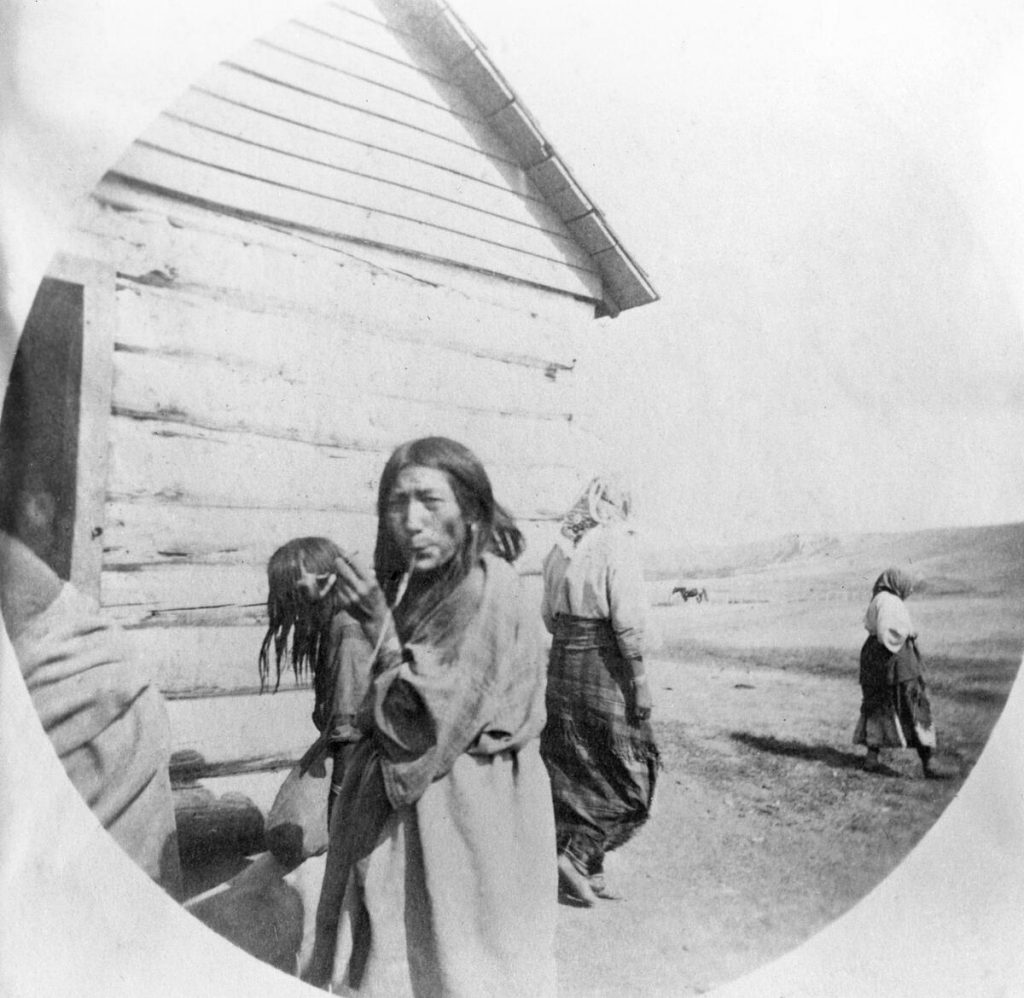

Sarcee (Tsuut’ina) camp, Sarcee (Tsuut’ina) reserve, Alberta, ca. 1899 (Glenbow Library and Archives Collection)

It’s reported in 1879-80 that Chief Red Crow remarked that the buffalo were gone. Efforts by Macleod and the NWT Council to regulate the buffalo hunt in 1877 were unsuccessful. Macleod then went to Ottawa to discuss the situation and provision for foodstuffs and more officers.

Macleod spent the rest of his career as a judge on the NWT Supreme Court and then as a member of the Legislative Assembly, with his seat moving from Fort Macleod to Calgary. He is remembered for dutifully navigating the newly-establishing Canadian presence on the prairies while gaining the trust of Indigenous leaders in the hope all could live together peacefully.

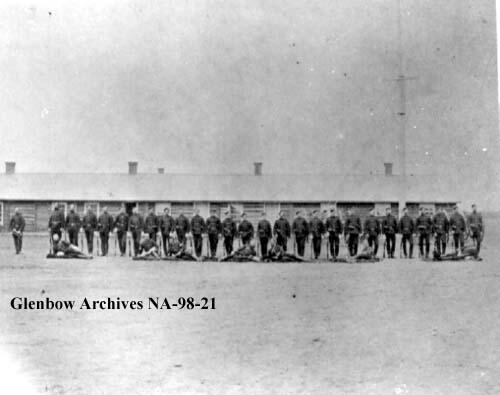

C. Troop North-West Mounted Police, lined up at Fort Macleod, AB, 1879 (Glenbow Library and Archives Collection)

The lack of buffalo forced Crowfoot to take his people to Montana to hunt, where they were exposed to theft and alcohol. Peace with the Sioux ended when they raided Crowfoot’s camp, which forced him to return to Canada.

The journey was long and arduous and the Blackfoot arrived at Fort Walsh, SK and then at Fort Macleod in desperate need of rations, which the authorities barely provided. At this point, the Tsuu’tina separated from the Siksiká and Chief Stamixo’tokan (“Bull Head”) petitioned for their own reserve, which was eventually granted.

By September 1880, Red Crow and the Blood tribe arrived at their reserve on the Oldman River, where they petitioned the government for food. They put to rest the seasonal round and started the construction of log cabins for the coming winter. Red Crow worked hard to avoid depending on the government, encouraging farming, ranching and education to instill self-sufficiency.

In 1881, the Kainai participated in what would be their last buffalo hunt. When they arrived at their reserve, they struggled to hunt from a fixed location, which was compounded by the lack of buffalo.

The hard winter of 1883-84 is known as the Starvation Winter because of the widespread hunger that afflicted Indigenous peoples. Foul and other game meat were hunted but this did not match the supply provided by the buffalo herds. It wasn’t until the 1890s that ranching began on the Kainai reserve, and another couple decades before farming was practiced.

The Starvation Winter upended faith in Treaty 7. Reverend McDougall came in for some hot criticism for his role in convincing Indigenous leaders to accept the transfer of traditional lands. He was accused by the Stoney of not being objective and for overstating the potential of agriculture in the area. Also, the Stoney were all placed on one reserve rather than receiving separate lands for each of the Bearspaw, Chiniki, and Goodstoney bands.

There were also administrative restrictions placed on the reserves. McDougall did not anticipate these and spoke out against the use of passes for those wanting to leave the reserve as well as the requirement to obtain the government’s permission to sell farm produce. He also failed in later attempts to expand the Stoney reserve.

Adding to the situation was political unrest by some Indigenous peoples.

Louis Riel, one of the founders of the province of Manitoba, had grown disillusioned with the treatment of the Métis. In 1879, he visited Crowfoot and tried to form a relationship with the Blackfoot based on their mutual grievances vis-a-vis the Canadian government.

It did not help the situation that the government’s new Department of Indian Affairs did not build trust with Indigenous peoples the way the NWMP had accomplished.

The bureaucrats were callous meddlers. They sought to regulate traditional hunting rights and thought the end of the buffalo would see Indigenous peoples accept reservation life. They thought Indigenous farming was primitive and therefore deserved only primitive tools (the commissioner who did this was fired some years later).

The authorities then reduced rations to the reserves. During a shortage of beef, they substituted in bacon, which was unfamiliar to Indigenous peoples. Red Crow sought to intervene while reigning in his people from raiding nearby ranches. He increasingly found his authority circumvented by the bureaucracy.

Crowfoot too was feeling a growing distrust towards the authorities. Arguments with bureaucrats led the NWMP to intervene, commanded by Charles Dickens’ son, Francis.

Relations with the government soured when Crowfoot openly defied the police in 1882 after Insp. Dickens tried to arrest one of the leaders of the Blackfoot for a theft. Ultimately, Crowfoot refrained from attacking the NWMP, and later the leader was found not guilty.

The department’s agent for Treaty 7 was relieved of authority and NWMP officer Cecil Denny at Fort Walsh, SK replaced him. Food supplies were restored and farm equipment was sent for the spring planting. However, the poor quality soil and lack of skills could not provide an adequate supply of food. Many of Crowfoot’s children died as a result.

Despite the government’s attempts to improve the situation, Crowfoot was growing sympathetic to the mutual plight of Indigenous peoples in the region as well as the Métis to the east. With Riel petitioning people to join his cause, there was once again an increasing risk of open conflict.

North West Rebellion/Resistance

After the 1870 Red River Rebellion/Resistance, Riel was exiled to the United States. He returned in 1884 to accept an invitation to advocate for Métis rights in Saskatchewan.

Discontent among the prairies’ Indigenous peoples was growing. The old ways of fur trading and working for HBC were disappearing, as was the bison, which was a vital staple. Compounding the situation was the failure of the government to deliver on promised opportunities from Indigenous land rights. On top of that, there was growing competition from easterners arriving in anticipation of the railway’s construction. There were also several years’ worth of bad harvests. The seeds of conflict were being sown.

Upon returning to Canada, Riel established a provisional government at Batoche, SK on 19 March 1885 and pursued land rights. Part of his effort included the formation of an armed force, which seized a church in Batoche and then moved toward Fort Carlton. Halfway to it, at Duck Lake, the force met the NWMP. Shots were fired and the police retreated to Fort Carlton, and then further back to Prince Albert.

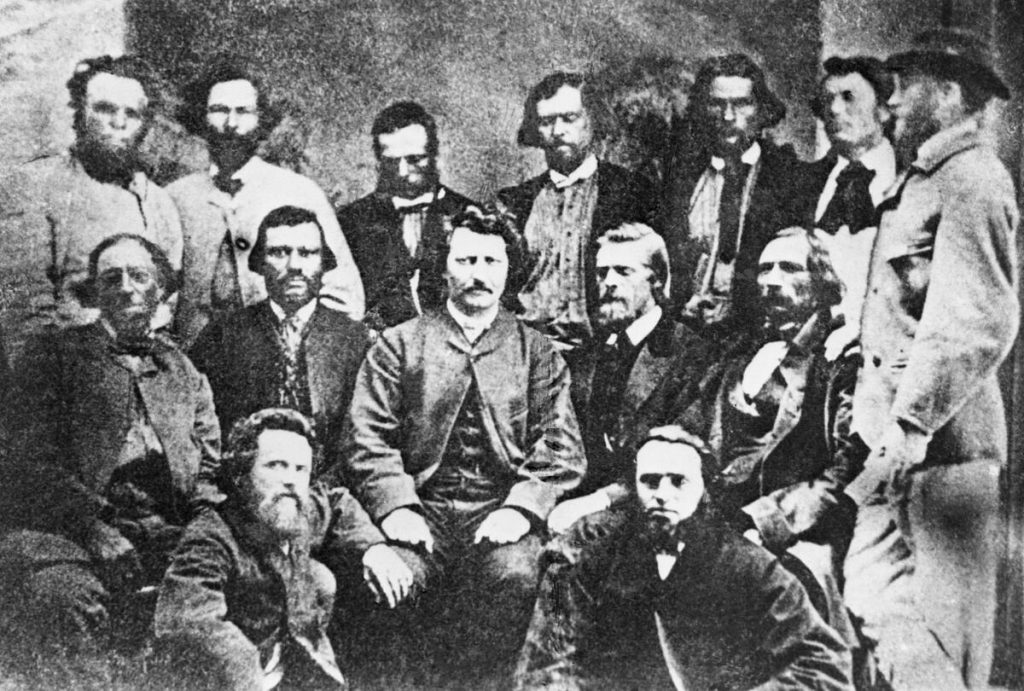

Louis Riel and his associates, ca. 1869 (Louis Riel Collection, University of Calgary). L-R back row: Tom Laroque; Pierre Delorme; Thomas Bunn; Xavier Page; Andre Beauchemin; Baptiste Beauchemin; Thomas Spence. L-R middle row: Pierre Poitras; John Bruce; Louis Riel; W. B. O’Donoghue; Francois Dauphinais. L-F front row: Bob O’ Lone; Paul Prue.

Upon hearing the news from Duck Lake, disgruntled Crees in Alberta took up the fight at Frog Lake. Without support from Chief Big Bear, a group of Cree attacked a church, killing nine men, including 2 priests. They proceeded to destroy the settlement and take prisoners, and then moved on to Fort Pitt to do the same. This was the extent of their pillaging as these Cree did not join Poundmaker’s forces at Battleford or Riel’s at Batoche.

Fearing that other settlements, including Calgary, were at risk of attack, the government asked Father Lacombe to intervene and retain the loyalty of the Cree and Blackfoot. Jerry Potts also went to secure the Blackfoot’s neutrality.

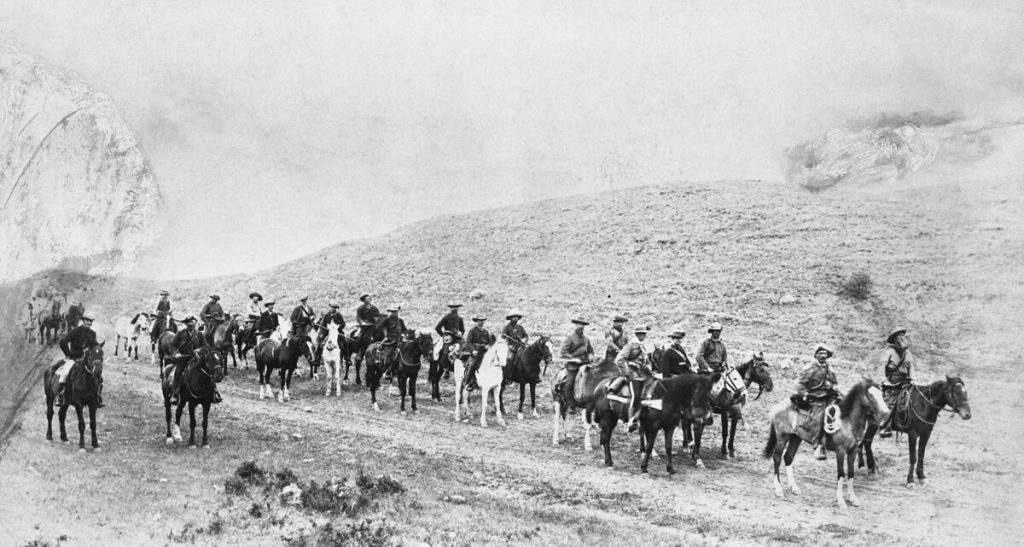

Meanwhile, volunteer units of ranchers and cowboys were recruited to patrol southern Alberta. One such formation was the Rocky Mountain Rangers at Fort Macleod.

During the crisis, the hotel (ca.1884) located at the crossing of the Red Deer River on the route between Calgary and Edmonton was turned into a fort by Lt. J.E. Bedard Normandeau. It is known today as Fort Normandeau and is the birthplace of today’s Red Deer. Another site along the route was The Spruces, a stopping house built in 1883 near Innisfail, AB. It’s the only one that remains today on the Calgary-Edmonton Trail.

At Calgary, a regular force was assembled under Major-General Thomas B. Strange. It marched to Fort Edmonton and prepared to meet the Cree at Frog Lake. They were an eager bunch – at one point some men opened fire on poplar trees waving in the wind that scouts had mistook for warriors.

Eventually, the Frog Lake prisoners were released. Eight leaders of the attack were tried and hanged, which stands today as the largest hanging in Canadian history.

Rocky Mountain Rangers in formation, southern Alberta, 1885 (Glenbow Library and Archives Collection). J. G. ‘Kootenai’ Brown, chief scout, in the lead. During the 1885 Riel Rebellion. Possibly near Medicine Hat.

Riel’s entreaties to Chief Crowfoot to join the resistance ultimately were not successful. The Blackfoot leader kept his people out of the fighting even as his adopted Cree son Poundmaker went and fought. The Stoney too signalled their loyalty to Canada, with some serving as scouts for the army. The Piikani and the Kainai refused to join too.

The situation in Saskatchewan was becoming untenable for Ottawa. A militia force of 3000 troops was mobilized and CPR manager William Cornelius Van Horne arranged for their rapid transportation to the region despite the remaining gaps in the new railway. A final total of 5000 men arrived. The force was split in two and dispatched northward to relieve Battleford and Batoche, respectively.

At the Battle of Batoche, Riel’s forces were overwhelmed by Canadian troops and he surrendered on May 15th. He was tried and executed for his leadership of the conflict. Poundmaker was sentenced to three years in jail, but ended up serving 6 months. He died shortly after returning home.

After the conflict, Crowfoot was hailed as a hero and honoured while travelling with Fr. Lacombe to Quebec. He stopped in at Ottawa and met Sir John A. Macdonald, calling him a brother-in-law.

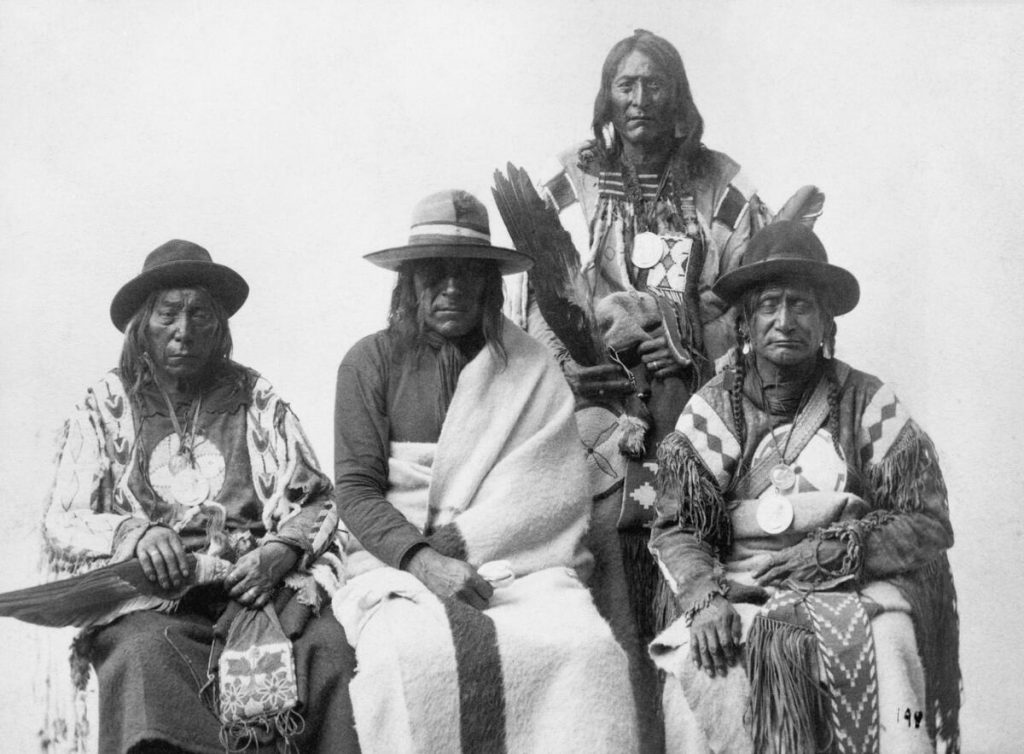

Group of chiefs of the Blackfoot Confederacy, 1885 (Glenbow Library and Archives Collection). L-R: Sitting on an Eagle Tail Feathers, North Peigan; Three Bulls, Blackfoot; Crowfoot (standing), Blackfoot; and Red Crow, Blood.

The last years of Crowfoot’s life were difficult. The government continued to interfere in Indigenous peoples’ lives and his family experienced tragedy. He nevertheless continued to seek peace between tribes, stopping raids and seeking negotiations, until his death in 1890.

Crowfoot’s dedication to his people and his trust in the NWMP led him to choose peace despite tensions and difficulties. He is remembered as one of the great founding leaders of Canada.

Leave a Reply