Stampede City

1900 to 1914

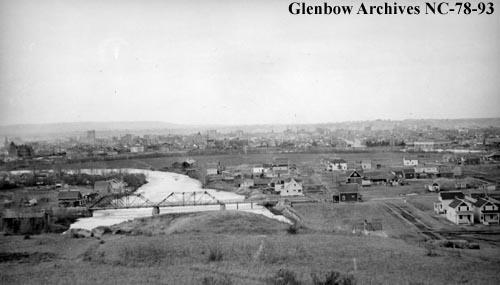

Let’s turn to the communities that started growing around the fast-developing City of Calgary. Because it was growing so quickly, and because of the importance of its commercial and industrial districts, the City started annexing the communities surrounding it.

Annexation

One of the first neighbourhoods to be annexed was Rouleauville in 1899, becoming today’s Mission community.

The first crossing of the Elbow River was here, a wooden bridge built in 1886. Father Lacombe orchestrated its construction to facilitate trade with St. Mary’s Catholic Mission rather than have farmers and traders go to Inglewood.

A steel bridge was built in 1912 and then Mission Bridge was upgraded in 1915, the first of its kind in Calgary – a concrete arch bridge rather than a steel through-truss bridge.

St. Mary’s was originally part of the 1873 Catholic Mission Notre-Dame-de-la-Paix, where a sandstone church was constructed in 1889. When Pope Pius X created the Diocese of Calgary in 1912, St. Mary’s church became a Cathedral and seat of Bishop John Thomas McNally.

Because the sandstone building was deteriorating, it was demolished in 1955 for a new building, completed in 1957. The current Cathedral is in the Modern Gothic style and holds the bells from the original church. Calgary sculptor Luke Lindoe created the concrete statue of St. Mary and Jesus that adorns the front tower.

Next to the cathedral is St. Mary’s Parish Hall, an Edwardian Classical building built with local sandstone. It was constructed in 1905 and became the centre of community life for Mission’s French-speaking Roman Catholics. In 1911, it was purchased by Canadian Northern Railway and passenger service began in 1914 to Edmonton and Saskatoon. Service ended in 1971 and it then became the home of the Calgary City Ballet in 1982 (today’s Alberta Ballet).

Along 2 St SW between 22nd and 23rd Avenues is a row of houses across from Holy Cross Hospital. One of them, Pattison Residence, is symbolic of these Edwardian style cottages. It was the home of Charles Pattison, an electrician who occupied the new home because trades were in demand at the time and he could afford the high rent.

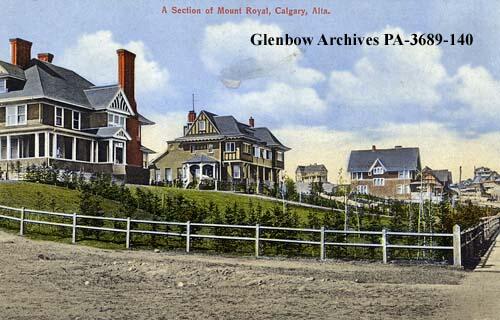

On the other side of Centre Street from Mission is Mount Royal. The area was far enough from downtown at the time that a tuberculosis sanatorium was built there in 1903.

Farther up the hill in 1904, wealthier families built their homes, the first along Royal Avenue. The area up the hill became known as American Hill owing to the presence of families from the United States. This raised some eyebrows among the Canadians of Calgary and so residents, among them future prime minister R.B. Bennett, asked for a name change to Mount Royal. The name came from Montréal, the hometown of CPR president William Van Horne, which is the 16th-century French version that translates into Mount Royal (“Mont Real”).

On the other side of Mission is Erlton, a community established in 1906. Today it’s the location of the oldest cemeteries in the city, which were laid just outside the original settlement.

Union Cemetery is the oldest public burial ground in Calgary, established in 1891. It holds up to sixty thousand of Calgary’s earliest residents, including the resting place of Sam Livingston, Sir James Lougheed, Col. James Macleod, William Pearce and John Ware. The cemetery was modelled on the Victorian garden concept, with curved paths and green spaces.

Because the first cemetery was located here, many others followed, including Jewish and Chinese Cemeteries. The Jewish Cemetery of 1904 is the first and oldest Hebrew burial ground in Calgary and was the burial place of many Jews from throughout southern Alberta. Before that, the only Jewish burial area was in Winnipeg. The land was purchased by the oldest Jewish community institution in Calgary, the Chevra Kadisha. It holds over 2300 places, including Alberta’s first permanent Jewish resident, Jacob Lyon Diamond.

Nearby, the Chinese Cemetery was established in 1908. It has design elements from Chinese culture, such as the graves being placed on a slope that faces east so the dead can face the rising sun. Over 1000 people are buried here from Calgary’s early Chinese community.

After Mission was annexed, parts of Victoria Park and Ramsay followed. Then in 1907, parcels of land in Mount Royal, Sunnyside, Hillhurst, Scarboro, South Calgary, Roxboro, Renfrew and Crescent Heights were annexed. A much larger area between McKnight Blvd and 59th Avenue S and between 37 Street W and Barlow Trail was annexed in 1910. Calgary next annexed land for its growth in the 1950s.

Just south of Inglewood was planned the community of Ramsay on land owned by W.T. Ramsay. Part of this area was the Mills Estate development (ca.1906), which Ramsay sold to A.F. Mills after the city annexed the area.

There are several notable buildings in this workhorse community on the original trail to Fort Macleod. One is the Calgary Cooperative Fur Farmers’ Assoc. Building (1912) with its sheet metal cladding and large signage. It originally served as a natural gas utility’s warehouse and then as a feed mill for fur-bearing animals. During WWI, it was the secret location of helium production used in airships.

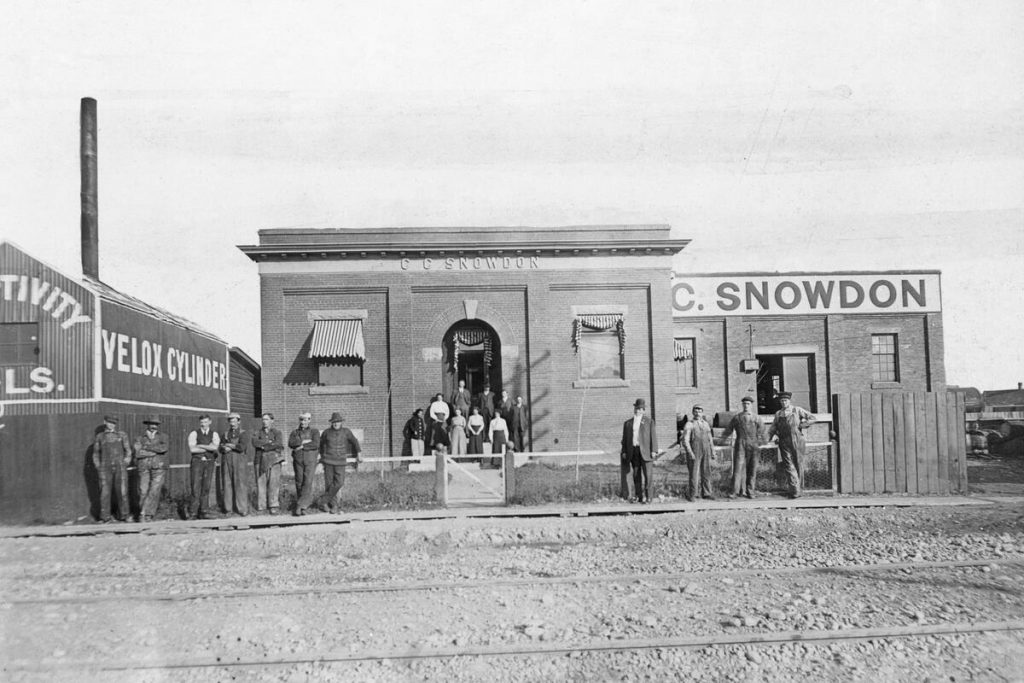

Another industrial building is C.C. Snowdon Oils Factory and Office (1910), located on the CPR railway line. For 70 years it operated as one of the first oil manufacturing and refining businesses in Western Canada. It’s a red brick building with sandstone detailing, a sturdy reminder of Ramsay’s industrial past.

A unique building in the area is Beers House (1907). Joseph Beers of Halifax, NS moved to Calgary and worked as a carpenter. He adapted the home to its current storefront style. When he moved to Forest Lawn, the building served as a grocery and convenience store for the next 7 decades.

Indeed, Ramsay is known for its many corner groceries, including Frank Block (1912), Alberta Grocery (1912) and Nevler Block (1915). The Beaudry Block (1911) is more similar to blocks in Inglewood, a 3-storey mixed-use residential and office building with storefronts.

Some parts of Ramsay were constructed prior to Calgary’s 1906 and 1911 housing regulations. McDonald Residence on Maggie St exemplifies this construction, when houses were built right out to the sidewalk and no alleyways were planned.

Some of the communities annexed by Calgary in the 1900s were established some decades prior. Sunnyside was first settled in the 1880s and was nicknamed New Edinburgh because of a concentration of Scots. Many of its first residents worked for the CPR or nearby sawmill. The area was connected to the south side of the Bow River by a wooden bridge, called Bow Marsh, in 1888.

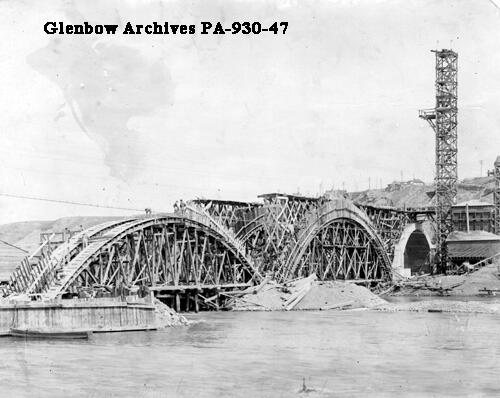

Calgary annexed the area in 1904 and replaced the bridge in 1906 with a steel bridge, named Louise Bridge after the deceased daughter of W.H. Cushing, former mayor and provincial commissioner of Public Works. Today’s reinforced concrete arched bridge was constructed in 1921, one of three such bridges in Calgary that were part of a new movement to beautify urban areas. The prior steel bridge was moved to the Ghost River.

The architectural styles in Sunnyside include 1880s CPR cottages, 1910s Edwardian Front Gable style houses, and 1920s Georgian Revival brick apartments. See the Sanderson Residence, for example (no, not the Sanderson sisters!), or Brower House.

Immediately to the west is Hillhurst and Hounsfield Heights. Hillhurst gained its name from Senator Cochrane, who named it after his birthplace, Hillhurst Farm near Compton, QC. The area was first homesteaded in 1890 by Thomas Riley and Georgina Hounsfield. Riley purchased the land from Cochrane and then sold it to the city.

After annexation to the city, expensive plots were sold, giving the neighbourhood the nickname “Mount Royal of the North”. The Dunsmoor Residence and Dando Residence are excellently preserved examples of the Craftsman style of bungalows. Riley also donated several acres to the city for a park, named Riley Park.

Up the embankment is Crescent Heights. Founded in 1895 by Archibald J. McArthur, it became its own town in 1908 and then a part of Calgary a few years later. Built there in 1914 was Bishop’s Palace, which was bought in 1918 by the Catholic Church. It became a home for retired priests in the 1970s, was sold in 1988 and demolished in 2013.

Settlement across the Bow River eventually required a permanent bridge out of downtown. A recommendation for a bridge was made as early as 1887 to replace Fogg’s Ferry, but it wasn’t until 1908 that a steel truss bridge was built. It was partially swept away in a flood in 1915.

In 1916, a major civic project was launched by city council to construct a concrete bridge. By this time, the City Beautiful movement was inspiring planning and design works. For Centre Street Bridge, a monumental and decorative character was including in the form of its arches and balustrades as well as its viewing platforms and light standards for pedestrian enjoyment. Most famously, the bridge is decorated with huge lion sculptures, a reflection of the country’s involvement in World War I, which are based on the lions on Nelson’s Column in London, England. Also adorning the bridge are buffalo heads and maple leaves.

At the foot of the bridge was built Calgary’s third Chinatown, which remains vibrant to this day. It was established in 1910 after landowners sold their properties in anticipation of the arrival of the Canadian Northern Railway (CNR), which forced out the Chinese tenants.

Some of the more wealthy Chinese bought property at the intersection of 2nd Ave and Centre Street. Here was built Canton Block, the first building of todays’ Chinatown. Locals in the area fought the establishment of a new Chinatown, but Lucy Kheong and Ho Lem made representations on behalf of the community to the city and eventually the new location was secured.

Meanwhile, other immigrant workers were finding employment in Ogden. Established in 1912, it’s named after a CRP Vice President and became the home of a CPR engine repair facility. Within it is the district of Millican Estates, named after the family that homestead the area in the early 1900s. Chinese workers established a laundry here as well, with Ogden Block serving as both business storefront and boarding house. The block is currently at risk of being demolished.

There was also growth a little further afield from Calgary. One area was Bowness. It was part of Cochrane Ranch in 1883 but was sold in 1890 to Thomas Stone and Jasper Richardson, who started Bowness Ranche. The name was chosen by Stone, who recalled a visit to Bowness-on-Windermere in the Lake District of England.

In 1908, lawyer John Hextall bought the land with the goal of establishing a residential suburb outside of Calgary. He personally financed a bridge and donated islands in the Bow River to the city for use as Bowness Park in return for the city running its streetcar into the community. While the park was popular, the community was not, with few lots selling by the start of World War I.

Businesses

Calgary’s communities were growing because practically everyone arriving was taking advantage of the opportunities to work or establish a business. This was helped of course by Calgary’s location on the railway.

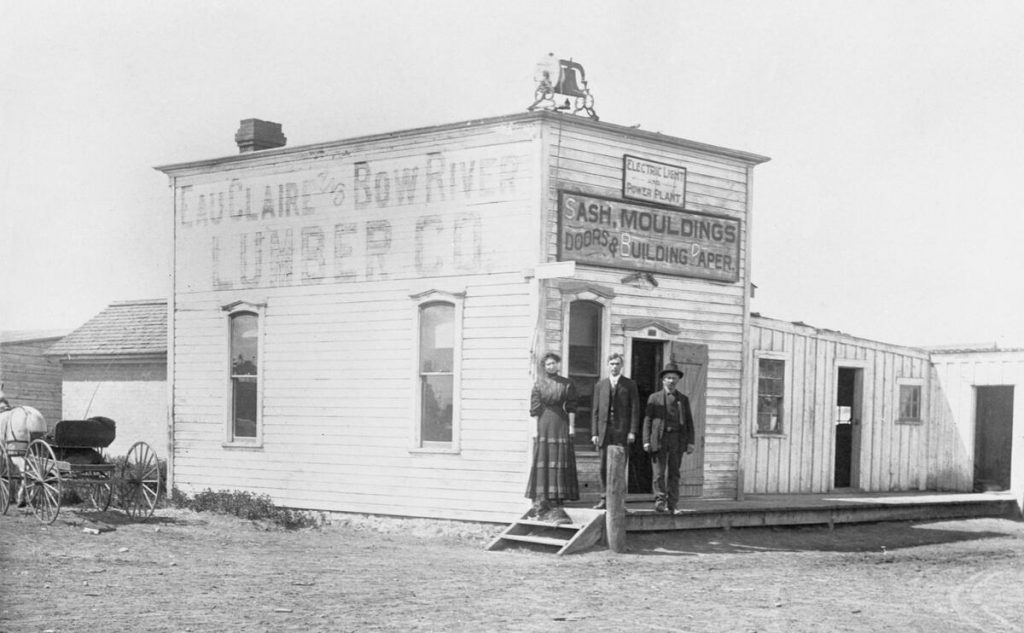

In 1886, business interests from Eau Claire, Wisconsin arrived and established Eau Claire and Bow River Lumber Co. just to the north of downtown. Peter Prince was the manager. To make log transportation easier, he and his team dug a channel in the river, which formed what would be called Prince’s Island Park in 1947.

In 1889, a weir on site began generating electricity, which was followed by a dam the next year. This was the beginning of Calgary Water Power Co. (today’s TransAlta). It had a 10-year exclusive contract to supply electricity to Calgary. By 1911, Calgary Power Co. could not meet demand and so it built the province’s first hydroelectric station at Horseshoe Falls, near Exshaw, AB.

The value of water to the area was known when William Pearce arrived in Calgary to work for the federal government and subsequently witnessed the drought of 1880. In 1904, he convinced the CPR to construct a canal to Reservoir No.1, known today as Chestermere Lake. The goal was to supply farms on CPR land in the arid area of Palliser’s Triangle, which would in turn encourage settlement and expansion.

By 1910, the area was marketed as having ready-made farms. Many from Great Britain made the trek out to southern Alberta to what became known unofficially as the English Colony, around Nightingale, AB.

The farms were designed for rapid settlement in the hopes of generating increased rail traffic. However, they were far from complete and the homes were little more than shacks. The weather also did not cooperate. The new canal and its secondary ditches were not filled by sufficient rainfall, hail storms ruined what few crops did manage to grow, and a severe winter in 1911 challenged the new arrivals.

Nevertheless, people banded together to survive and form communities. Some did leave, with their plots sold to Canadians or Americans, who had more experience farming the harsher conditions. Today’s Bassano, Irricana and Crossfield towns have their roots in these early communities.

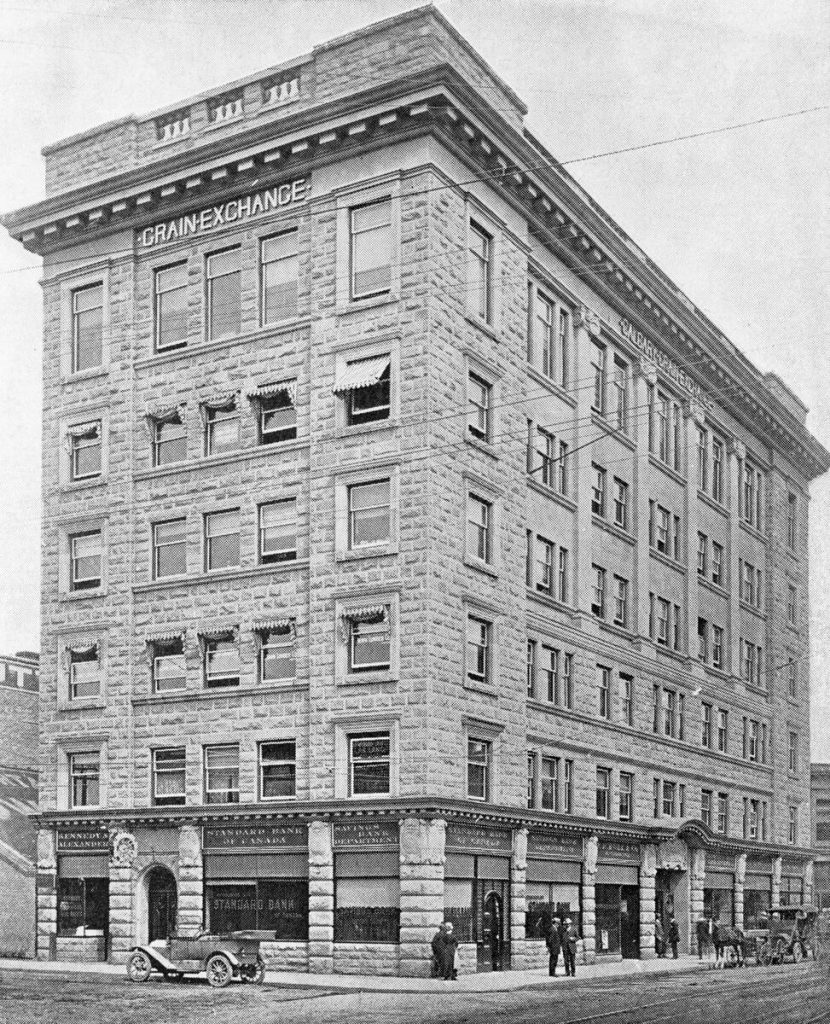

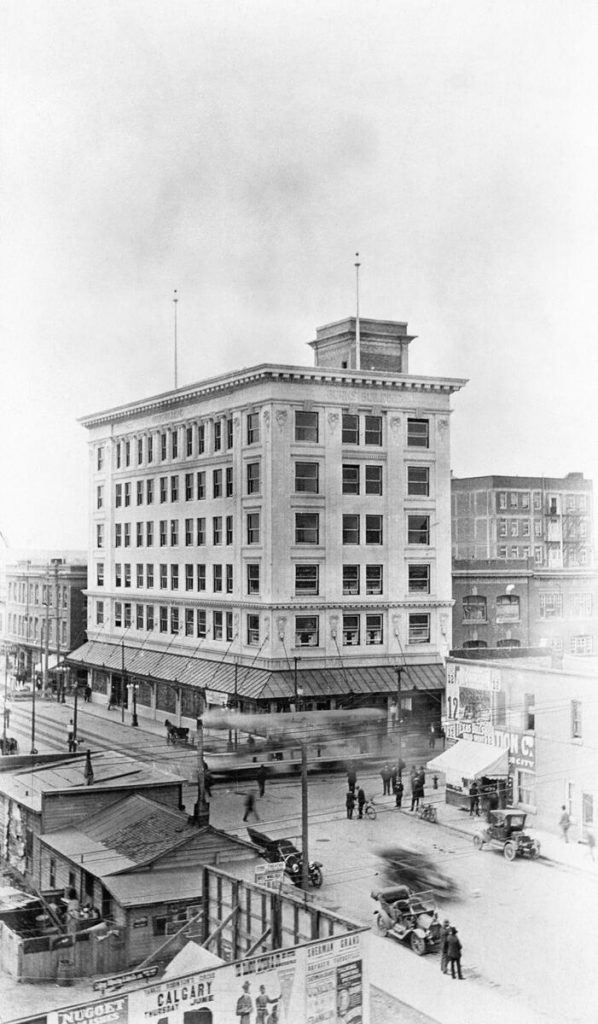

By 1900, the Bow Valley was producing more agricultural and industrial goods than any other region in Alberta. Calgary was the centre of the farming sector, which was cemented when the Grain Exchange was built in 1909.

William Roper Hull was a successful rancher and businessman. He founded the Calgary Grain Exchange, which was housed in the Hull Building. It was designed by William Bates, one of the first western architects of Calgary’s commercial district. He also designed Hull House, several Mount Royal homes, and St. Mary’s Cathedral.

The Grain Exchange became a notable landmark as the tallest building in Calgary at the time and was built with sandstone in Edwardian Neoclassical style. Its construction foreshadowed the many skyscrapers located in downtown Calgary today, and was a fine location for my brother’s wedding.

Just as farms were being established all throughout Alberta at the turn of the century, the original large-scale ranches had largely failed. Severe winter weather didn’t help. In 1906-7, the “Winter of the Blue Snow”, there were no chinooks. To make matters worse, a late autumn rain was immediately followed by rapid freezing, which made it difficult for cattle to graze. Scores of them died, bringing financial ruin to many. Ranchlands were split up and sold off, making way for the next generation of ranchers, in particular a group who would help make Calgary famous.

One was A.E. Cross, who owned Calgary Brewery and the A7 Ranch (see May’s article). Another was George Lane. Lane was from Iowa and arrived in Alberta via Montana in 1883 to work as a ranch foreman for the North West Cattle Co.

Lane went into business for himself and eventually purchased Bar U Ranch. He raised prized show horses and made Bar U internationally famous. He went on to serve as a Liberal MLA in 1913 and hosted Edward, the Prince of Wales, at Bar U in 1919. Lane was one of 11,000 Americans who had travelled northward by 1900 and integrated into British North American society, along with 7000 British. Alberta’s American lineage largely dates back to this time.

Another rancher was Archibald McLean. He had lived and worked as a ranch hand, and eventually managed and then owned CY Ranch, near Taber, AB. He raised cattle for export to London before selling up and running as an independent MLA in Lethbridge in the 1909 provincial election, Alberta’s second general election. He ended up crossing the floor to join the Liberal party in the provincial government as a minister.

The last person to comprise the “Big Four”, and probably the most notable, was Patrick Burns. Burns had homesteaded in Manitoba and learned the butchery trade by supplying meat to the CPR crews building the railway.

He built his first slaughterhouse on the east side of the Elbow River outside Calgary in 1890. He expanded the business by moving up and down the supply chain, establishing retail businesses (Burns Foods) and purchasing ranches, including cattle near Olds and sheep on Rosebud Creek. He also purchased Hull’s ranch at Fish Creek.

As Calgary’s growth increased, so too did Burns’ businesses. He established meat packing plants all throughout Western Canada and in Seattle, started over 100 retail meat shops, exported to the UK and Japan, and he ventured into dairy and produce.

His dealings in ranch property meant Burns ended up a huge landowner. Many of the ranchers who had been forced to sell accused Burns of unfair dealings. He and his business partners were exonerated by a commission tasked with investigating the cattle industry. In the end, Burns held enough land that at one point he boasted he could walk from Cochrane to the United States without leaving his property.

Burns was appointed an independent Senator by Prime Minister Bennett in 1931 and was named Alberta’s Greatest Citizen by the Calgary Herald in 2008 – “His story is the story of Alberta. His struggles, his dreams, his success and philanthropy define the very core of our western character.”

The Greatest Outdoor Show on Earth

Ranching, cattle drives and farming were significant aspects of the Calgary and area economy in the early 20th century. The growth of the region’s settlements and the advent of new technologies, such as the automobile, brought major changes to life on the prairies. Most notably, the cowboy lifestyle was fading away.

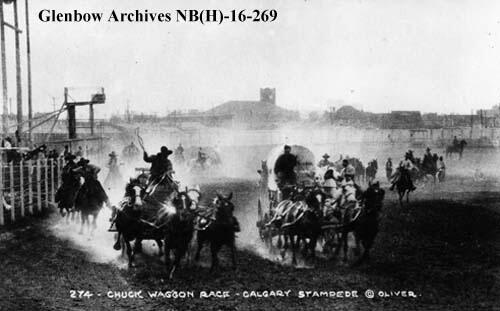

Cowboys lived on horses and were the backbone of every ranch. They were persistent, strong workers who were each expected to watch 1000 head of cattle. Herd roundups in springtime were huge affairs, when dozens of men and hundreds of horses headed out over thousands of acres. Every night, they returned to the chuckwagon camps to rest and refuel. Nowadays, reenactments of chuckwagons packing up and racing each other to the next campsite occur at rodeos throughout North America.

The work of the cowboy made them independent minded. They were also noted for their chivalry, loyalty and neighbourliness. They also rolled into town to gamble, drink, fight and, um, obtain services from locals.

Over the decades since the NWMP’s arrival, settlements had appeared and expanded, and the arrival of the railway drew work away from the countryside. This translated into falling demand for transient workers. As the 20th century wore on, the cowboy’s lifestyle on the Canadian prairie became increasingly rare.

One man was enthralled with the cowboys of the Old West and resolved to capture some of their culture somehow.

Guy Weadick was born in New York state in 1885, the son of a railway worker. As a child, he was taken with cowboy culture thanks to his California relatives and to travelling shows, including Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show (see April’s article). As a teenager, he followed his passion and left to work on ranches where he learned skills and eventually performed himself as a trick roper.

He arrived in Calgary in 1908 to take part in the Dominion Exhibition, which drew 100,000 people with its promise of progress. For the first time, Calgarians saw the demonstration of an airship. Weadick thought Calgary was ripe for an agricultural showcase that was much more than a travelling show of tricks and games.

Meanwhile, George Lane had been invited by President William Howard Taft to show his Percheron breeding horses at an exhibition in Seattle. There, Lane too thought an agricultural show could work for Calgary, which could highlight the modernity of the West while celebrating its past.

The idea of the Stampede was percolating at the same time as the Ranchman’s Club was expanding. It had contracted for the construction of a new building for the private club, which was completed in 1912. The building is in the Renaissance Revival style, a precursor to the Chicago and Beaux Arts styles. Its symmetrical facade and paired windows with terracotta decorations meant it stood out as a hallmark of Calgary’s business community. It also testified to an element of Calgary’s culture that sought to emulate and respect its British roots and the institutions of the Commonwealth.

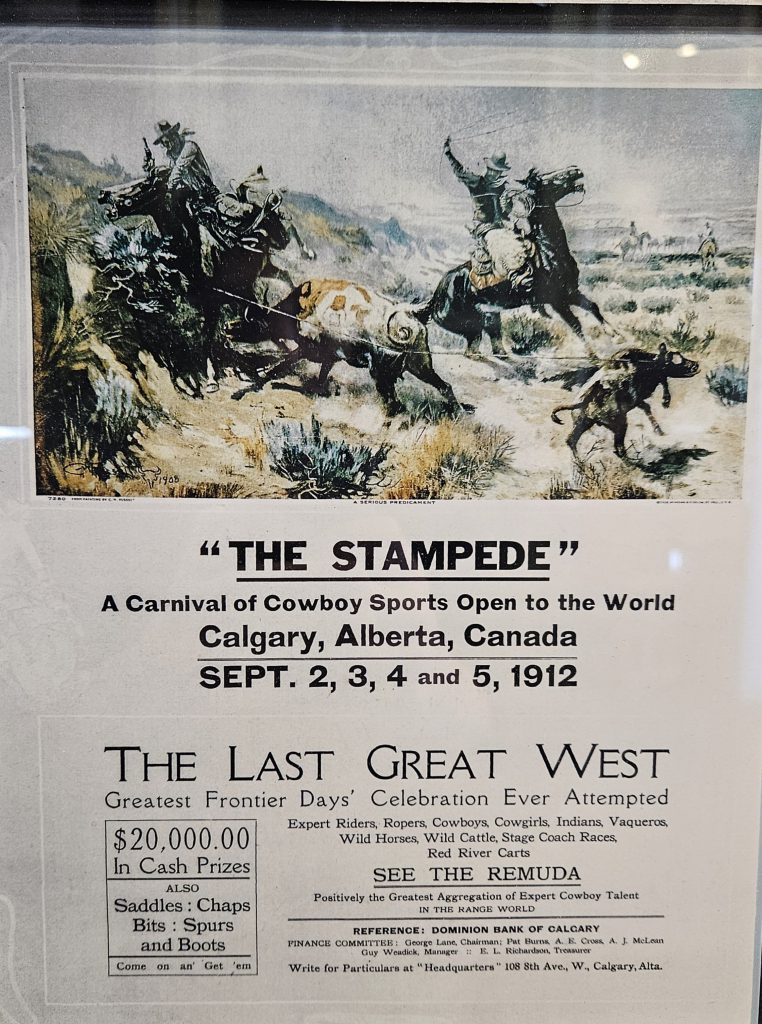

CPR livestock agent H.C. McMullen agreed with the idea for an agricultural show in Calgary. In 1912, McMullen asked Weadick to return to Calgary from his overseas travels so he could drum up support for an international rodeo with prize money.

However, the Industrial Exhibition board (who had run their own fair since 1886) told Weadick the idea was not compatible with the rapidly growing urban environment. It was also thought the idea would only work in a bigger city.

At the Alberta Hotel, a friend of George Lane overheard Weadick’s setback. Lane met with his fellow ranchers Burns, Cross and McLean – “The Big Four”. They loved the idea and pledged $100,000 (about $2.7 million today) to set up Weadick’s ag and rodeo show. Weadick was instructed to “make it the greatest thing of its kind in the world”. They also thought it could be one last ride into the sunset for Cow Town.

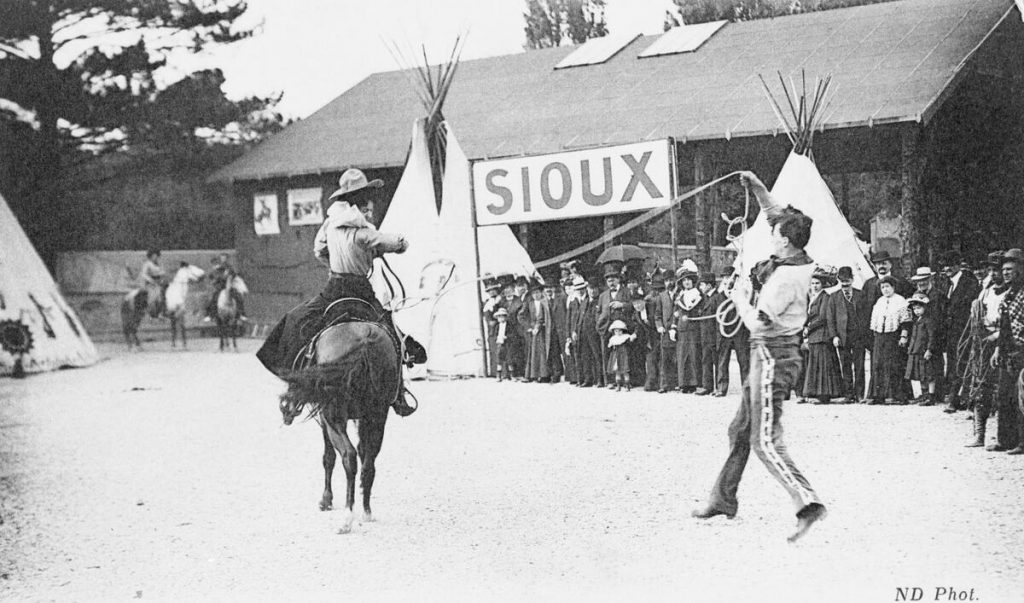

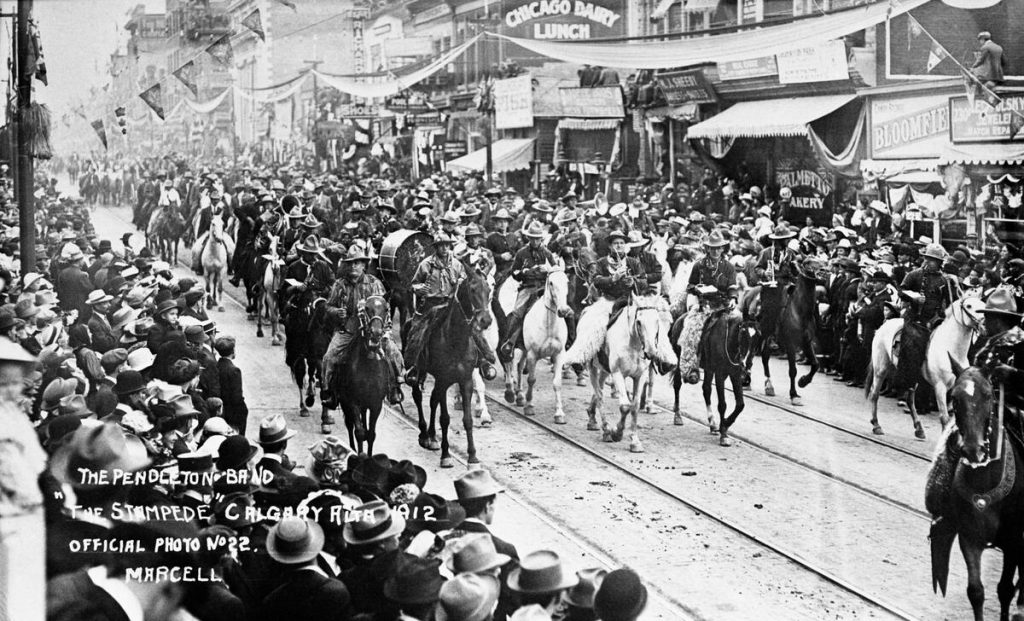

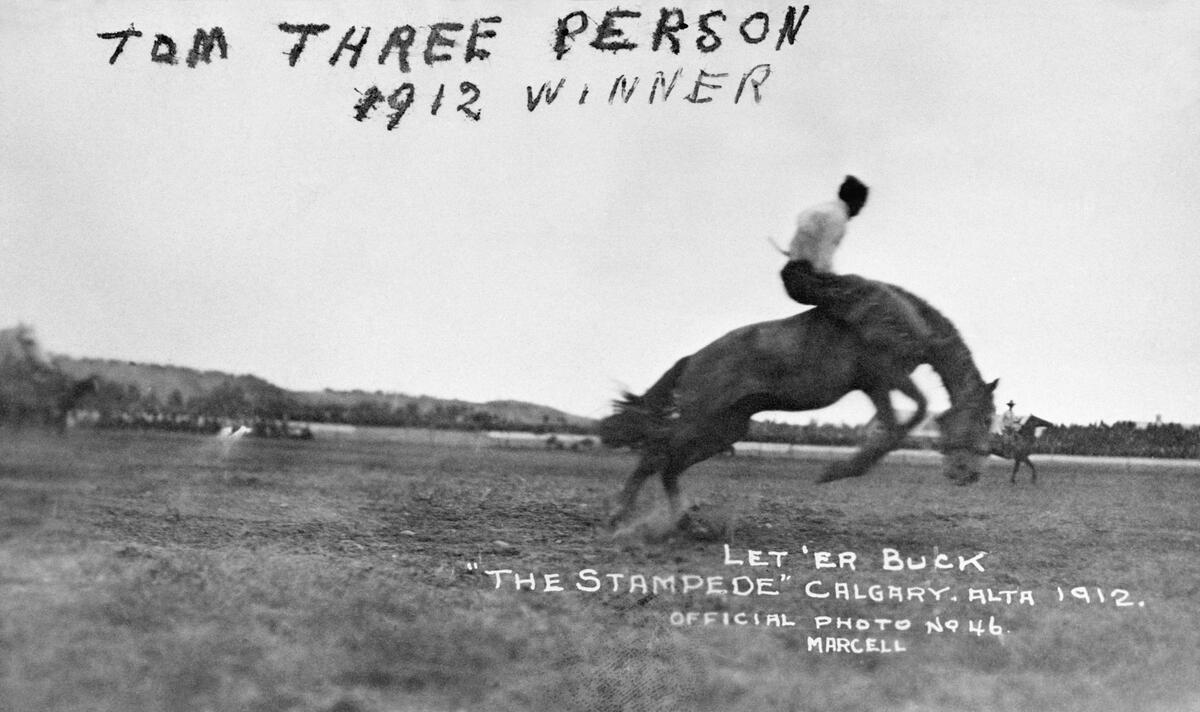

What we think of today as a city tradition, the Calgary Exhibition and Stampede, was first held in 1912, which started on September 2nd and ran for six days. Some 80,000 people witnessed the pageant parade.

The rodeo in Victoria Park drew 25,000 people, a remarkable feat for a city of only about twice that size at the time. Included among the crowd was the son of Queen Victoria, the Governor General of Canada. Horsemen all the way from Mexico called vaqueros performed their skills.

Weadick also wanted a cultural component to the Stampede, and so several artists exhibited their works. It has seen artists locally and from all over the world display their works. One famous example is the Rembrandt painting displayed at the Stampede in 1927.

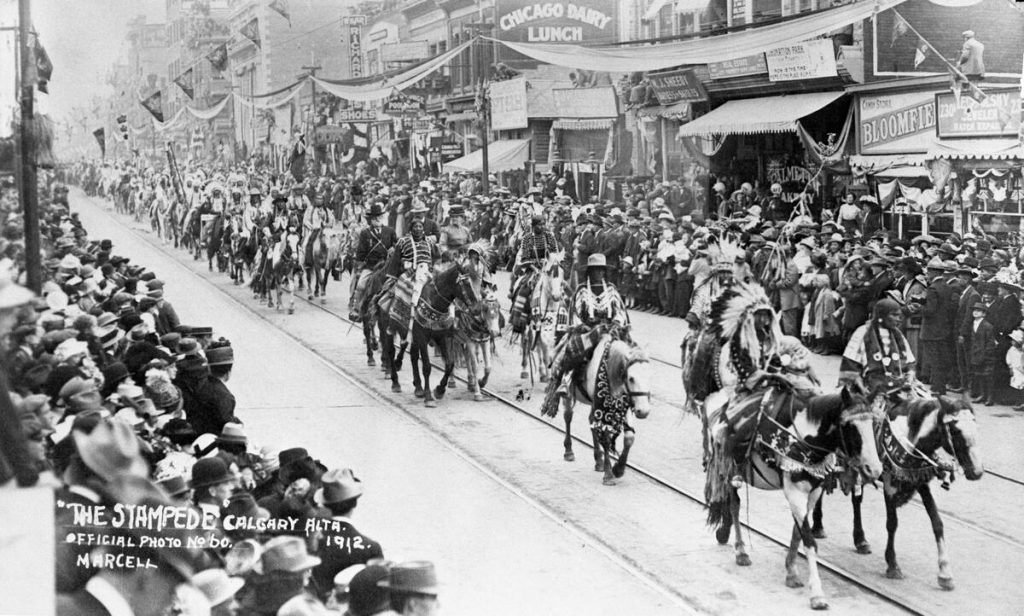

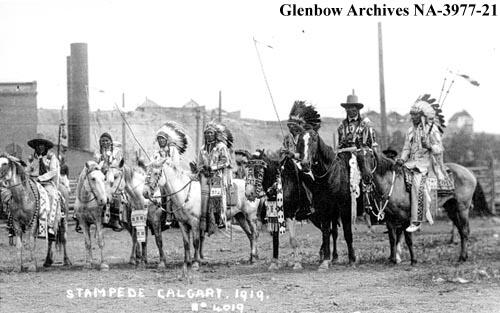

Weadick also insisted that Indigenous peoples participate in the event. At the time, they could not perform their cultural practices on reserves owing to Indian Act regulations. There were some at the time, including Rev. John McDougall, the son of the Rev. George McDougall, who advocated for the right of Indigenous peoples to practice their culture. To make the point, McDougall helped arrange performances at various exhibitions.

To accomplish his goal, Weadick brought Sir Lougheed and R.B. Bennett to bear on Ottawa to allow dispensation for the participation of Indigenous peoples. Weadick then liaised with Siksika elder Ben Calf Robe to organize their attendance. And so Indigenous peoples were welcomed at the first Stampede, with 2000 arriving to take part. Their contingent led the parade, with NWMP officers following behind.

During the Stampede, Indigenous peoples stayed at camps on the grounds or outside the city. The Siksika were out near Strathmore, the Kainai and the Piikani camped on land across from today’s Big Four Building, the Iyarhe Nakoda were located in Montgomery, and the Tsuut’ina set up in Killarney. This was the beginning of the Stampede’s Indian Village/Elbow River Camp.

The first Stampede generated some buzz. Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and the Duchess of Connaught attended the Stampede. He was Canada’s Governor General at the time and the only British prince to hold the role. For their arrival, 20,000 lights outlined City Hall and a “Welcome to Calgary” sign was mounted on the clock tower.

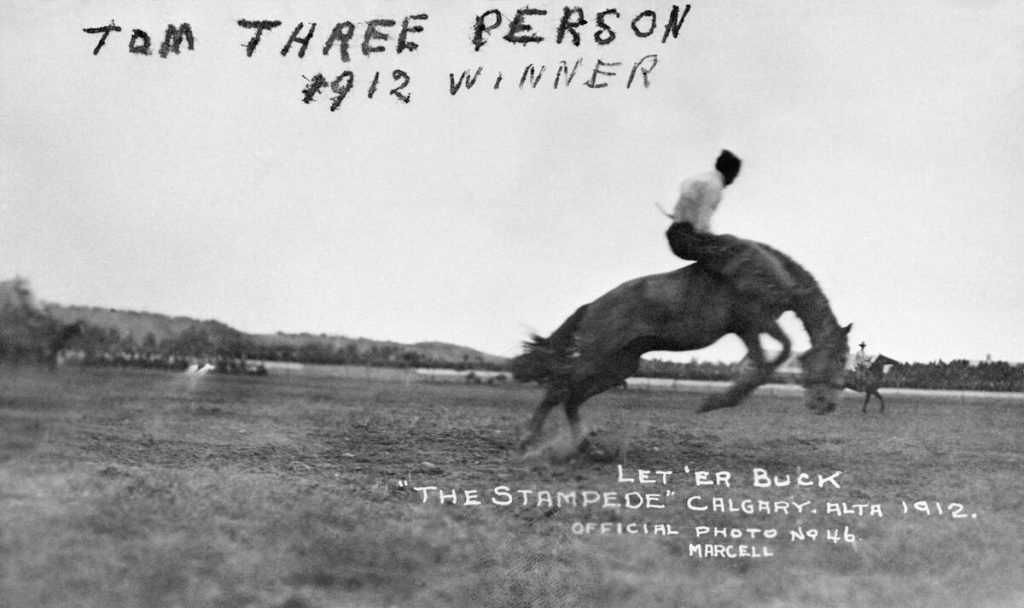

There was especially high praise for Tom Three Persons, a Blood Tribe member who captured the bronc riding title on a tough horse named Cyclone, riding him to a standstill (today rider’s only have to last 8 seconds). Florence LaDue, Weadick’s wife, won the title of Lady Champion Fancy Roper.

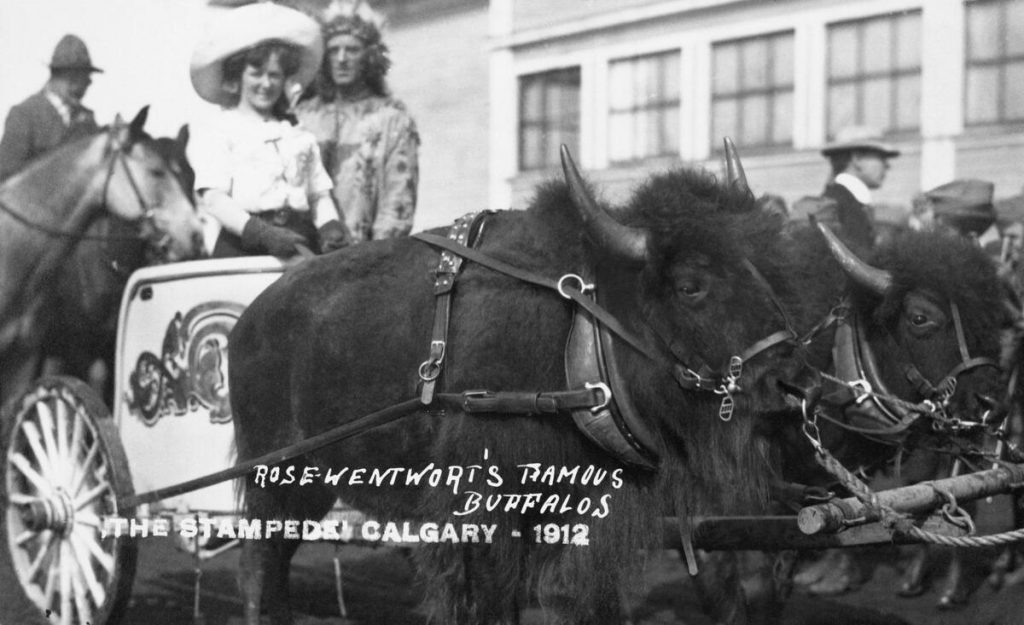

Also present at the first Stampede were buffalo!

Despite being wiped out on the plains, many buffalo survived and were part of herds traded between Canada and the United States. One effort at rescuing them began with six orphaned calves near the Montana-Alberta border that Sam Waking Coyote took to Flathead Indian Reservation, MT.

The Government of Canada ended up buying this herd in 1908 so it could establish Buffalo National Park near Wainwright, AB. The purpose of the park was to protect and grow the buffalo herd. Experiments were also conducted to cross buffalo and cattle to produce “cattalo”, but these were not successful.

The park closed in 1940 and was turned over to Canadian Forces Base Wainwright. The herd was moved to today’s Wood Buffalo National Park. Other herds were also salvaged in Manitoba, including by Metis James McKay and Irishman Charles Alloway.

Despite the first Stampede’s success, its huge cost and the start of World War I prevented another show from being held until 1919. There was also criticism of a lack of organization and of the cost of a ticket (which Calgarians know full well).

The success led Weadick to take his idea to Winnipeg and New York, but only Calgary came calling and established it as a recurring event. The Stampede was also being heavily promoted by businesses and the newspapers, which called for it to be an annual event. When WWI ended, Calgary reached out to Weadick and asked him to promote a Victory Stampede.

The Victoria Pavilion, today the oldest building still in use at the Stampede, was built just in time for the 1919 Stampede. It housed a livestock judging ring and was part of a master plan for the year-round of the exhibition. True to the Stampede’s roots, a Wild West show was performed when it opened. In later years, it hosted a variety of events, including curling, church services, pet shows, political speeches, and boxing and wrestling matches. These matches evolved into the famous Stampede Wrestling competitions and TV show, the precursor to today’s WWE.

The second iteration of the Stampede was another big success. There was no question it would be held again. In 1923, a partnership was inked with the Exhibition. For the third Stampede, rancher Jack Morton introduced chuckwagon racing and of course, the pancake breakfast. The annual tradition of the Calgary Stampede was born.

At one of these breakfasts, the mayor was playfully abducted by a group of Blackfoot and Tsuut’ina, a tableau arranged by a Herald reporter. They helped Mayor George Webster cook pancakes on the streets of downtown. And there you have the reason politicians of every stripe from the many corners of Alberta and even Canada descend on Calgary in early July to flip pancakes.

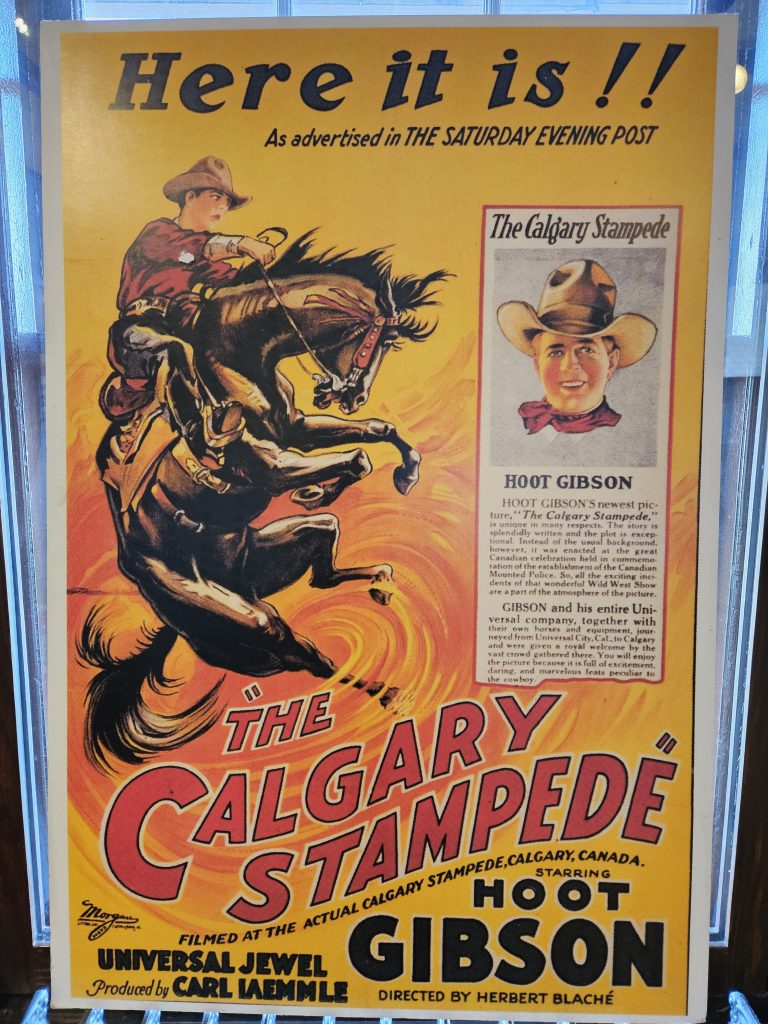

The Stampede was so successful, it even found its way into Hollywood, thanks again to the lobbying of Guy Weadick. The 1925 silent movie The Calgary Stampede starring Hoot Gibson and Virginia Browne Faire was a box office success. The director rigged up a covered wagon with a hidden camera to surreptitiously capture the Stampede as it was happening.

Thanks to Guy and Flo Weadick, the Big Four, Indigenous peoples and to Calgarians, the city continues to embrace its roots, rightfully adopting the moniker of Stampede City. Every July, all Calgarians are welcome to “get your head in a cowboy hat!”

Speaking of hats, Calgary today is famous for gifting a white hat to visitors, a symbol of Western hospitality and exuberance. The Calgary Hat Company was purchased in 1911 by Morris Shumiatcher, whose Jewish family had moved to Calgary from Russia in 1910. He renamed it the Smithbilt Hat Co. and began a partnership with the Stampede to produce western wear for spectators.

In the 1947 Stampede parade, the company’s white cowboy hats were worn by prominent businessmen and others. When Calgary played against Ottawa for the Grey Cup in Toronto in 1948 (we won!), 250 Calgary supporters were there wearing white hats. They presented one to the mayor of Toronto and rode a horse into the lobby of the Royal York Hotel (which itself became a CFL tradition).

In 1950, Mayor Don MacKay started presenting white hats to visiting dignitaries, and a tradition was born. In 1983, the white hat was made part of Calgary’s new flag.

The Stampede has been a tremendous success. It’s a part of the fabric of Calgary and continues to respect our past and honour those who care for and work the land.

At the same time, it’s not lost on anyone that Calgary’s economy is now based on a different kind of natural resource, which we’ll explore next month.

– Anthony Imbrogno is a volunteer with The Calgary Heritage Initiative Society/Heritage Inspires YYC

– All copyright images cannot be shared without prior permission

*Special thank you to the volunteers at the Calgary Stampede’s Sam Centre, who shared valuable information.

Where to See this Era

Nose Creek Valley Museum, 1701 Main St S, Airdrie, AB T4B 1C5

Canmore Museum, 902B 7 Ave, Canmore, AB T1W 3K1

Kananaskis Visitor Information Centre, 1 AB-40, Kananaskis, AB T0L 2H0

Bragg Creek Trading Post, 117 White Ave, Bragg Creek, AB T0L 0K0

Okotoks Museum and Archives, 49 N Railway St, Okotoks, AB T1S 1K1

Okotoks Art Gallery and Visitor Information Centre, 53 N Railway St, Okotoks, AB T1S 1K1

Check out https://legacyfarmproject.ca/, Strathmore, AB

Brooks Aqueduct National Historic Site, 142 Range Road, Newell County, AB T1R 0E9

Anniversary Park, 208 W Chestermere Dr, Chestermere, AB T1X 1B2

Museum of the Highwood, 406 1 St SW, High River, AB T1V 1M5

Claresholm & District Museum, 5126 1 St W, Claresholm, AB T0L 0T0

Nash Restaurant, 925 11 St SE, Calgary, AB T2G 0R4

Deane House, 806 9 Ave SE, Calgary, AB T2G 2Z2

Ramsay walking tour

Warehouse District walking tour

Beltline walking tour

First Baptist Church, 1301 4 St SW, Calgary, AB T2R 0K4

East Village walking tour

King Eddy, 438 9 Ave SE, Calgary, AB T2G 1R1

Rundle Ruins, 631 12 Ave SE, Calgary, AB T2G 1C5

Sunnyside/Hillhurst walking tour

Sunalta walking tour

Central Memorial Park and Library National Historic Site, 1221 2 St SW, Calgary, AB T2R 0W9

St. Mary’s Cathedral, 219 18 Ave SW, Calgary, AB T2S 0C2

Mount Royal walking tour

Union Cemetery, Cemetery Rd. and Spiller Rd. S.E., Calgary, AB T2C 4H3

Chinatown walking tour

Bowness Park, 8900 48 Ave NW, Calgary, AB T3B 2B2

Prince’s Island Park, 698 Eau Claire Ave SW, Calgary, AB T2P 5N4

The Coutts Centre for Western Canadian Heritage, Willow Creek No, 26, Nanton, AB T0L 1R0

Sam Centre, Stampede Grounds, 632 13 Ave SE, Calgary, AB T2G 1E8

Video

National Film Board: Stampede

Further Reading

Donna Livingstone, The Cowboy Spirit: Guy Weadick and the Calgary Stampede, Greystone Books, 1996.

Canmore’s history

Bragg Creek’s history

Strathmore’s history

“Calgary’s Transit History“, The Gauntlet, 2018

Calgary Chinatown’s history

The Hong Lee Laundry digital preservation project

Early Alberta Hydro History

“Calgary Stampede: The Beginning“, Calgary Herald, 2016

The beginning of Elbow River Camp

The origin of the Stampede pancake breakfast

The story behind the movie The Calgary Stampede

Leave a Reply