Fort Calgary

1810 to 1875

In Part One, we left off with the people who started calling the Calgary area their home. They lived alongside Indigenous peoples, who traversed the area during the seasonal round.

Meanwhile, the stirrings of Calgary’s formal founding were taking place in other parts of the still young nation of Canada. These stirrings would eventually result in the establishment in 1875 of a North West Mounted Police (NWMP) fort at its present location on the southwest shore of the Bow and Elbow rivers’ confluence.

The March West

The Dominion of Canada was founded when the British Parliament in London passed the British North America Act in 1867. Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory were transferred from HBC to Canada with the 1868 Rupert’s Land Act. Altogether, the area became the North West Territories (NWT). The transfer was enacted for several reasons, one of which was to counteract the purchase of Alaska by the United States in 1867. Another was because HBC no longer had the moral authority and financial ability to govern such a vast landmass.

Parliament facilitated the sale of HBC’s lands to the Dominion in 1870 after some delay caused by the Red River Rebellion/Resistance. It was because of this event that the province of Manitoba was founded in July 1870.

With administration came responsibility, which was immediately evident to the new government in Ottawa.

Fort Whoop Up whisky fort was the nickname for Fort Hamilton. “Whoop Up” possibly referred to bull train drivers yelling “whoop” to their bulls. Or perhaps it referred to the intoxicated antics that occurred in the fort’s vicinity. One of its notorious products was Whoop-Up Bug Juice, an alcohol spiced with ginger, molasses and red pepper. Perhaps the name is from a trader responding, “They’re still whoopin’ ‘er up!”, when asked about the fort’s operations.

With HBC no longer in authority and the fur trade in decline, outlaw activity and American trade expanded, both occurring well beyond the reach of Canadian authorities. The famous lawless American Wild West was coming north.

It took the Cypress Hill Massacre for Ottawa to take action and assume its responsibilities out West.

The event occurred on 1 June 1873. A party of American hunters and Métis traders had left Fort Benton, MT in pursuit of horse thieves, who had robbed them during their winter hunt. When the party encountered a small group of Assiniboines, they accused the group of stealing the horses. While no horses were held by the Assiniboines, tensions escalated as accusations flew and liquor was consumed.

Accounts differ on what led to the shooting, but in the end, superior American firepower overwhelmed the Assiniboines, killing 13 of their men and 1 hunter was killed. Artifacts of the battle are kept at Fort Walsh National Historic Site on the Saskatchewan side of the Cypress Hills.

When reports of the shootout reached the NWT Council and the province of Manitoba, both governments called on Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald to put in place a territorial police force. The force would help establish lawful order, quell tensions, patrol the U.S. border, avoid American annexation of the NWT, and help establish trust with Indigenous peoples.

Work was already underway on a “Mounted Police Force for the North-West Territories” due to the sale of HBC’s lands. However, a debate on whether to create Métis units delayed action. After the massacre, the federal cabinet passed orders to appoint nine officers and begin recruitment.

The force was modelled on the Royal Irish Constabulary, a combined military, police and judicial operation. It even adopted the famous British red coat military uniform (quite distinct from the U.S. Army’s blue uniforms). Capable young men between 20 and 35 were sought and offered 75 cents per day (about $20/day today) for a 3 year term, at the end of which they would receive 160 acres of land.

Before the NWMP could assume its duties, including investigating the massacre and extraditing the Americans to face trial, they first had to get to the prairies.

Inspector Éphrem-A. Brisebois, a veteran of the Union Army, was sent to recruit a force of 150 men and march them from Port Arthur, ON to Lower Fort Garry north of Winnipeg before winter blocked the overland route. Another 150 men travelled through the States to meet the first contingent at Fort Dufferin, MB. Once assembled, their orders were to proceed west to deal with what the authorities described as the “band of desperadoes” around Fort Whoop-Up.

The March West began on 8 July 1874. The 275 member force was headed by Colonel George French and was supported by 339 horses, 142 oxen and 187 wagons stretching across 4 kilometres.

Despite being trained all winter by Sam Steele, the young men were inexperienced and the horses were unsuited for draught work. They made slow progress across the prairies, averaging about 24 km per day. Hunting buffalo for food also slowed them down, with many never having seen one before. As the force headed into rougher prairie, some of the men suffering illnesses were left behind.

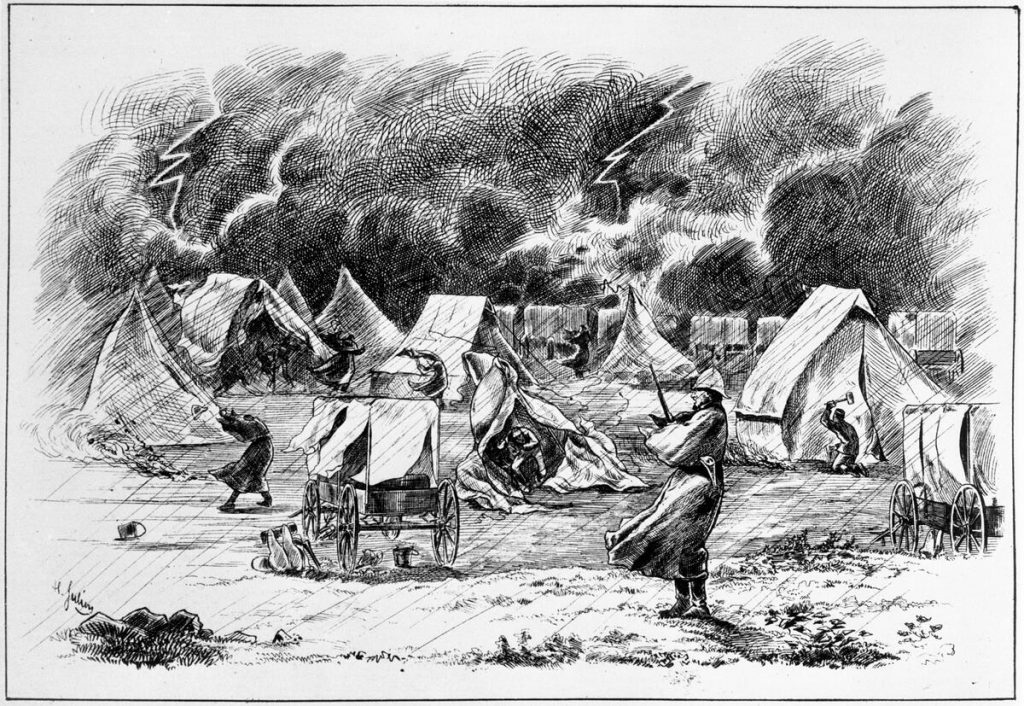

NWMP camp during storm, 1874 (Glenbow Library and Archives Collection). Sketched by Henri Julien during trek of NWMP from Dufferin, MB, and published in Canadian Illustrated News.

The force split again on August 1st, with about 20 sick men and the weaker horses sent to Fort Edmonton. They arrived exhausted around Halloween just as the weather was turning. The southern expedition continued westward along the 49th parallel. A tornado ravaged their camp, they respectfully met a group of Sioux from the U.S., and they passed by a sacred Indigenous rock art site at La Roche Percee, SK. They finally reached the Cypress Hills on August 18th, having suffered illness, the death of horses and more men left behind.

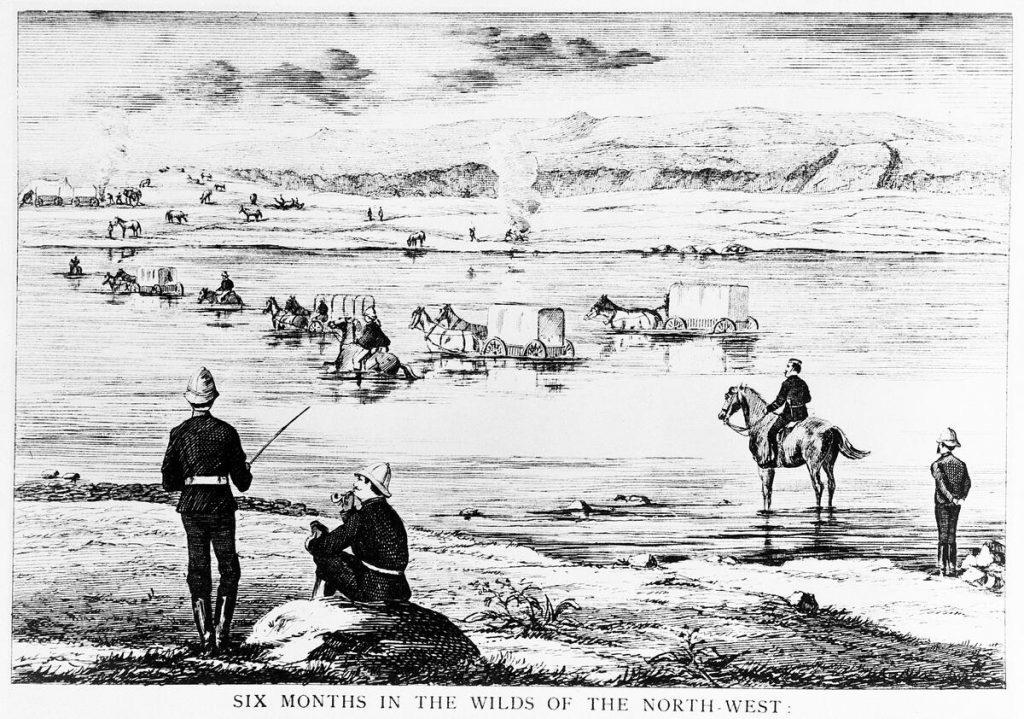

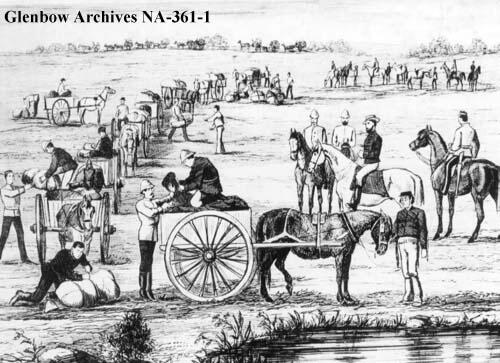

North-West Mounted Police crossing, Belly River, Alberta, 1874 (Glenbow Library and Archives Collection)

Upon arrival in southern Alberta, Col. French could not locate Fort Whoop Up and instead camped in the Sweet Grass Hills to await resupply from Montana. He engaged the services of half Scot, half Blood local hunter and interpreter Jerry Potts, also known as Ky-yo-kosi (“Bear Child”). Potts had lost many of his mixed family to alcohol and went on to fight the illegal trade with the NWMP for the next 22 years. At this point, French headed back to Manitoba and instructed Lt.-Colonel James Macleod to find the whisky fort.

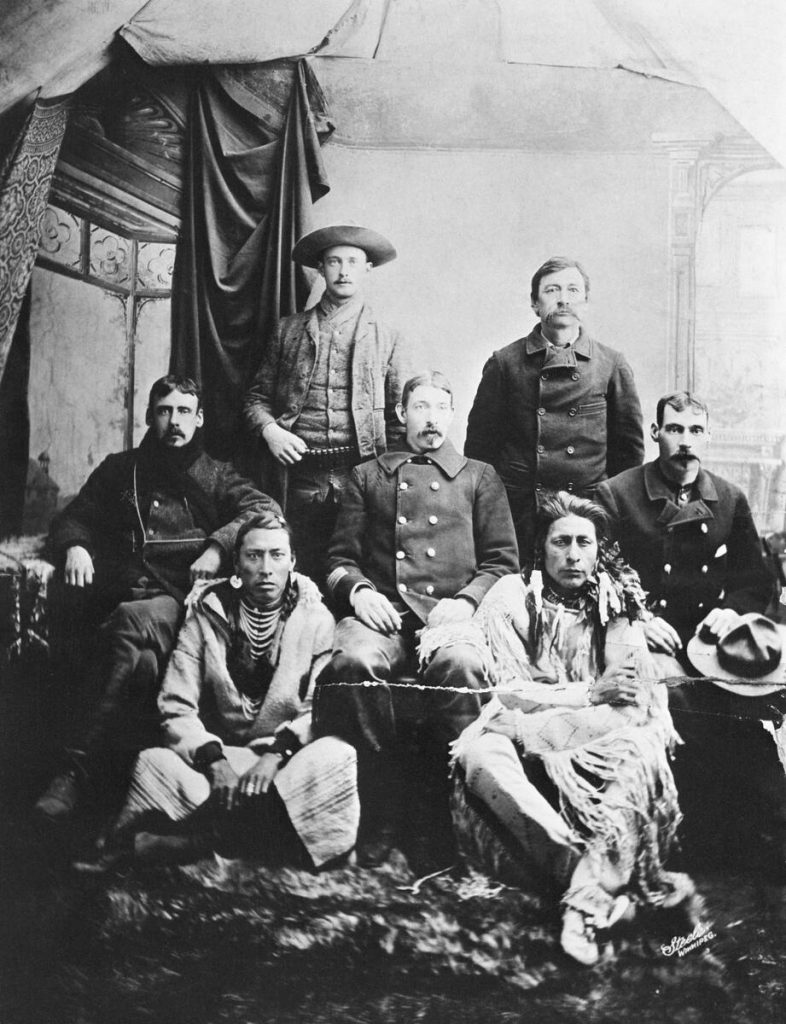

North-West Mounted Police scouts at Fort Macleod, Alberta, 1890 (Glenbow Library and Archives Collection). L-R back row: Mr. Hunbury; Jerry Potts. L-R middle row: Cecil Denny; Staff Sergeant Chris Hilliard; Sergeant George S. Cotter. L-R front row: Black Eagle; Elk Facing the Wind.

The tired but resupplied force finally arrived at Fort Whoop Up on October 9th. Such was their luck they discovered the whisky traders had abandoned the fort, who knew the Canadian “Red Coats”, or Mounties, were on their way.

The 1400 km march was over. Historian William Baker described it as “a monumental fiasco of poor planning, ignorance, incompetence, and cruelty to men and beasts” (see Baker, The Mounted Police and Prairie Society). Others thought the men were brave and extraordinary in their determination and perseverance to survive the conditions and any logistical mistakes to arrive prepared to fulfil their duty.

With no one around to police, the force went up the Oldman River to construct a new fort to combat illegal trading. Along the way, they were met by John Glenn on his return from Fort Benton, MT, who sold them luxuries such as flour and syrup.

Jerry Potts chose the site for Fort Macleod and construction began on 18 October 1874 of a square building 230 by 230 feet. It was located on a peninsula on the Oldman River and became the NWMP HQ in 1876. The fort moved to its present day location in 1884.

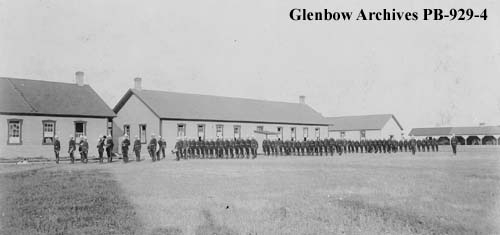

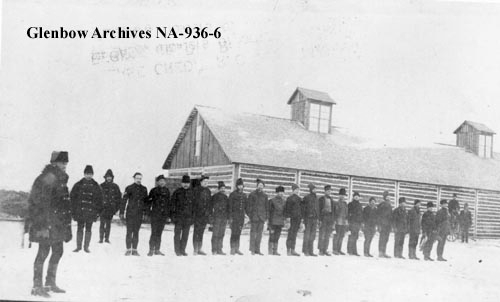

North-West Mounted Police inspection, Fort Macleod, AB, ca. 1894 (Glenbow Library and Archives Collection)

Once established, the work against the whisky traders began. Relations between the Indigenous peoples of the area and the newly arrived force were helped by Potts, who arranged the first meetings between Macleod and the region’s leaders, including Chiefs Isapo-Muxika (“Crowfoot”) and Mi’k ai’stoowa (“Red Crow”). He could explain to each party the cultural expectations and immediate concerns of the other.

Crowfoot was seeking peace and security for his people from the turmoil in Montana. Macleod’s experience as a hunter on his father’s farm north of Toronto, his family’s good relationship with the local Ojibwa people, and his philosophy training at Queen’s University prepared him to act as ambassador. Soon thereafter, Piikani Chief No-okska-stumik (“Three Bulls”) led the NWMP to their first arrests: whisky traders who were cheating his people. They were caught, fined and jailed.

Macleod was then given permission by the U.S. government in December 1874 to enter Montana Territory to investigate the Cypress Hills Massacre. Macleod arrested a group of people but they either escaped or were released for lack of evidence, with the American commissioner refusing extradition. He even charged Macleod with false arrest before dropping it. Then in 1876, two men were caught and put on trail in Winnipeg. Again, lack of evidence was a problem.

Even though the case ultimately failed, the pursuit of justice for Indigenous peoples by the Canadian authorities proved significant in the coming years, when negotiations for Treaty 7 were underway and when trust between peoples was put to the test during the 1885 North West Rebellion/Resistance.

The effort by the NWMP officers also showed the locals that the Mounties were determined to “always get their man”. Indeed, the Mounties’ reputation originates from a Fort Benton newspaper article from 1877 about the arrest of three whisky smugglers, with the reporter writing, “They fetch their man every time”. Hollywood writers later adapted the sentiment into today’s catchphrase for Canada’s national police force.

Fort Calgary

Despite the NWMP’s arrival, American smugglers remained active throughout southern Alberta. In response, Col. Macleod planned to establish two new forts after the winter of 1874-75.

Inspector James Walsh was sent to the Cypress Hills while Inspector Brisebois was ordered to lead 50 men to establish a fort along the Old North Trail about halfway between Fort Macleod and Fort Edmonton.

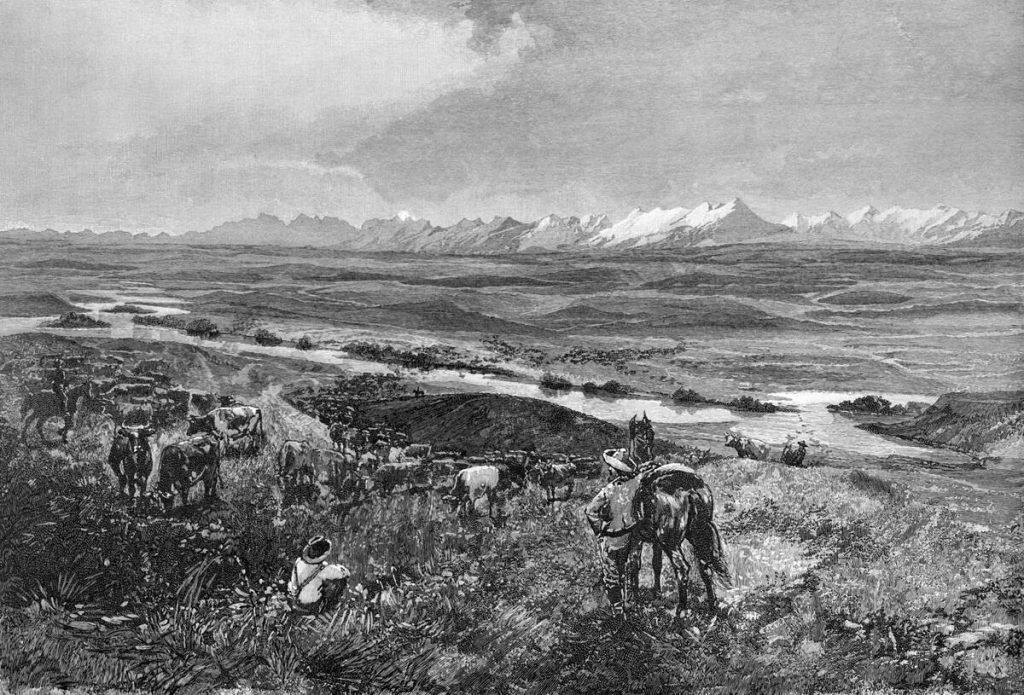

The Old North Trail is a route in the foothills that parallels the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains. It’s been used for thousands of years as a path for travellers since it traces a food-rich, sheltered route in between the harsher montane and prairie environments. The Trail runs through the Calgary area because it contains accessible river valleys and hunting lookouts.

Peter Fidler was provided with a map of the Trail by Siksiká chief Aka-Omahkayii (“Old Swan”). Fidler was active throughout Blackfoot territory, surveying and trading for HBC. He was granted permission by Old Swan to build fur posts, including Chesterfield House in 1791 near Empress, AB where the Red Deer River meets the South Saskatchewan. Fidler maintained a trading relationship with the Blackfoot, who also provided protection. Old Swan taught Fidler the travel routes throughout the area, including ones that led down to the Missouri River. He also learned that the Trail goes as far south as Mexico and up north to the Yukon.

With more forts in the region, the Old North Trail was increasingly becoming a vital trade and transportation corridor, which was noted by Captain Palliser. Establishing and reinforcing the NWMP’s presence directly on the Trail to police the bull trains would greatly assist in ending the trade of illegal whisky.

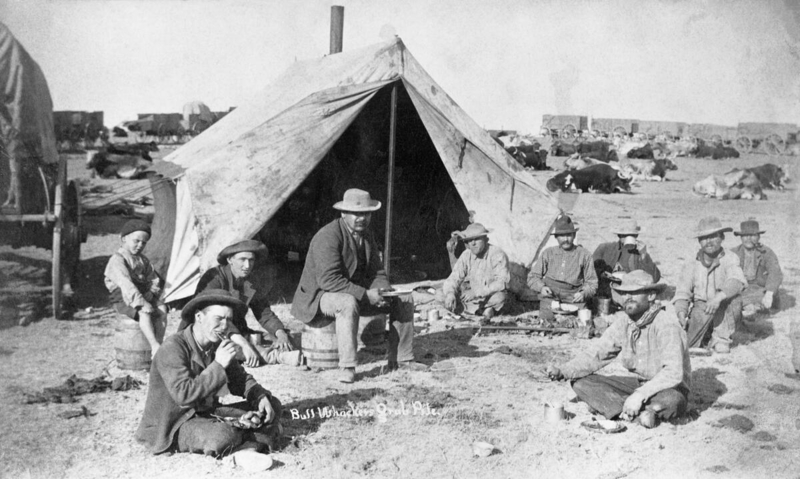

Bull train camp, Benton-Macleod trail (from Fort Benton, MT to Fort Macleod, AB), ca. 1880s (Glenbow Library and Archives Collection)

As we’ve seen, there were many who were aware of Calgary’s advantages along the Old North Trail, and they started to permanently inhabit the area. After a rendezvous near today’s Red Deer with a company of men from Fort Edmonton, Brisebois turned south and arrived at the Bow River escarpment, likely near today’s Rotary Park in Crescent Heights. The confluence of the Bow and Elbow Rivers was spotted as a good site for the new fort. Nearby was Father Doucet, who met the force and accompanied them to the river. On 25 August 1875, Officer George C. King became the first NWMP officer to cross the Bow River and arrive onsite.

Father Lacombe, Father Constantine Scollen (the first English-speaking Catholic missionary in Alberta) and Métis Alexis Cardinal had built a small log cabin on the banks of the Elbow, near the Métis settlement, in 1873. Another mission was constructed by the priests further south, on the future site of Holy Cross Hospital.

Reverend George McDougall also arrived from Morleyville (today’s Mînî Thnî) to meet the NWMP. He had established a mission there in 1873 after driving 11 cows and one bull down from Fort Edmonton (and so may have been the first to move livestock across southern Alberta). During one watch on Spy Hill, McDougall noted a buffalo herd that stretched to the horizon, estimating it at 500,000 head, perhaps one of the last of the large herds to travel through Calgary. John Glenn was also on hand to build stone fireplaces in the barracks and sell supplies.

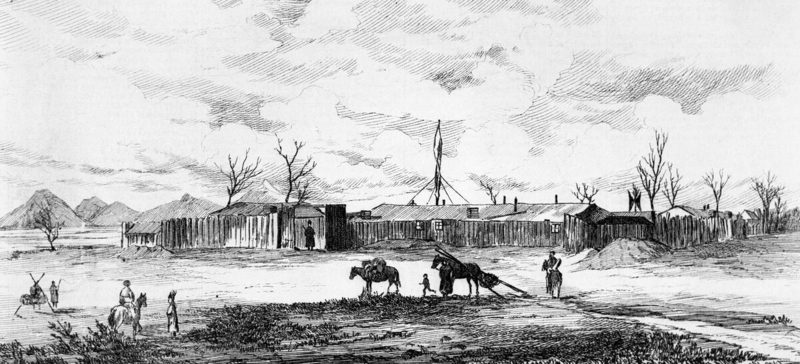

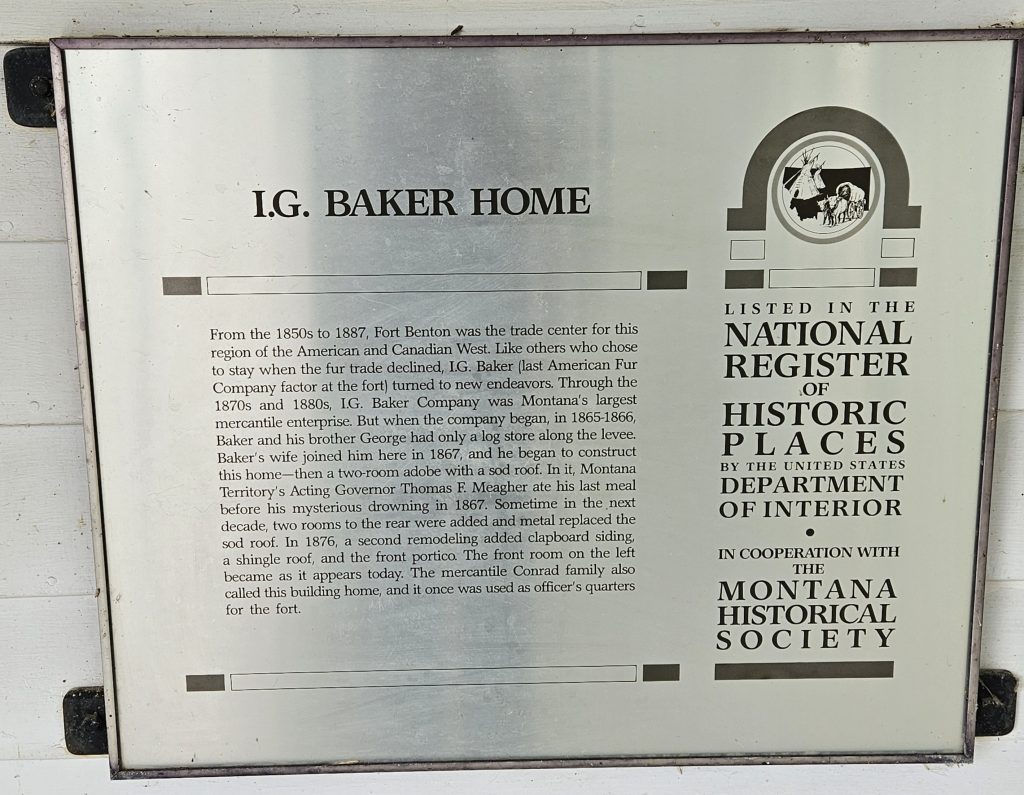

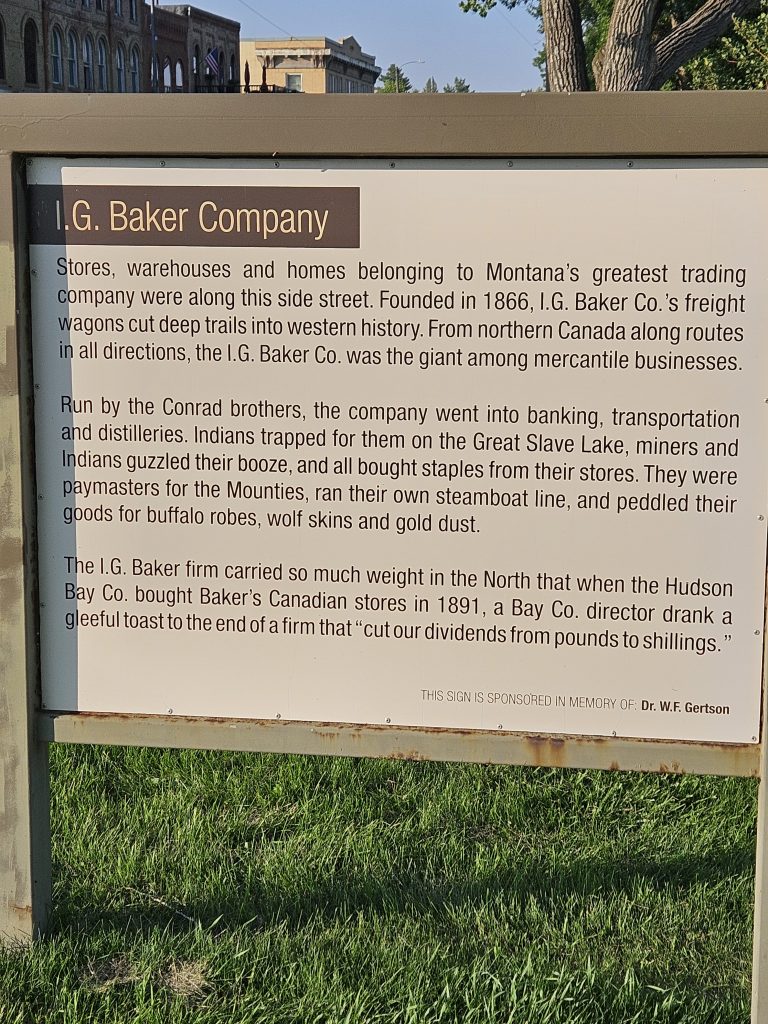

I.G. Baker Company was contracted to build the new fort. It was bounded on all sides by a wooden palisade, made of spruce and pine. Inside were several structures, including barracks, stable, guard room and storage sheds. All this cost the government $2,500 (about $70,000 today).

Stable parade, North-West Mounted Police post, Calgary, ca. 1880s, (Glenbow Library and Archives Collection)

At Christmastime 1875, the nicknamed “Bow River Fort” was christened Fort Brisebois. The unilateral decision to name the fort was not appreciated by NWMP Commissioner Acheson Irvine nor Col. Macleod, who had a fraught relationship with Brisebois owing to disciplinary problems amongst the men. Col. Macleod instead suggested naming it Fort Calgary.

He put forward the name because of his good memories visiting Calgary House, a castellated Gothic mansion built in 1823 that faces Calgary Bay on the Isle of Mull, Scotland. The name “Calgary” (in Scottish Gaelic, Chalgairidh) comes from the Gaelic cala ghearraidh, meaning “hard sandy beach by the pasture”, or Beach of the Meadow. There may be little sand along the Bow River, but it’s a name that fits the location where buffalo herds forded the river and where Indigenous peoples established their seasonal round camps. The name was made official by Ottawa in 1876.

Calgary House, Isle of Mull, Scotland, 2018 (Andrew Wood, via Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license)

With the fort established, more Métis arrived from Fort Edmonton with wagons in tow. They constructed log cabins on both sides of the Elbow River. By winter 1875 a little settlement had sprung up (a census in 1881 recorded 172 people, two-thirds of whom were Métis).

One man, Rousell, had worked for HBC before going independent. His family ended up cultivating land around the northern end of Scotsman’s Hill, which he sold to Wesley Orr upon the arrival of the CPR in 1883. Alongside these early homesteads, HBC constructed a post in 1876 – today’s Hunt House, the oldest building in Calgary that remains on its original site.

Hunt House (H.B.C. Log Cabin) 806 – 9 Avenue SE, March 2018 (Benlarhome, via Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license)

Meanwhile, more homesteaders started arriving. John Glenn was joined by friend Sam Livingston to become the first to cultivate cereal crops in the region in 1876.

Like Glenn, Livingston had made a go at mining before finding himself on the prairies. He traded buffalo hides north of Fort Edmonton and also traded with the mission at Rouleauville. He then homesteaded near Glenn on the Elbow River. A schoolhouse on his land was named Glenmore School after a village near his birthplace in County Wicklow, Ireland. He was the first person in Calgary to use mechanized equipment for farming.

Fort Calgary was completing its mission, but its living conditions were harsh at first. For one, it was not well insulated. Also, Insp. Brisebois did not discipline those who were skirting their duties, causing dissension amongst the force. When Brisebois expropriated a cook stove for his own quarters during a bitter cold snap in the winter of 1875-76, the men complained directly to Macleod. By August, Brisebois was out.

Having a security force close by opened up the surrounding area to homesteading and trading opportunities. I.G. Baker Co., which had given up running illegal whisky forts, instead set up a post and storehouse next to the fort, making Calgary an important part of the legal trading network from Fort Edmonton to Fort Benton. The relocation of HBC’s post from Ghost River to the Elbow across from the fort cemented the area’s importance.

It seemed the March West was a success, so much so that the need for a fortified outpost diminished, with only four constables present in 1880.

What would the future hold for those who were calling the Calgary area “home”? We’ll find out next month.

– Anthony Imbrogno is a volunteer with The Calgary Heritage Initiative Society/Heritage Inspires YYC

– All copyright images cannot be shared without prior permission

Addendum

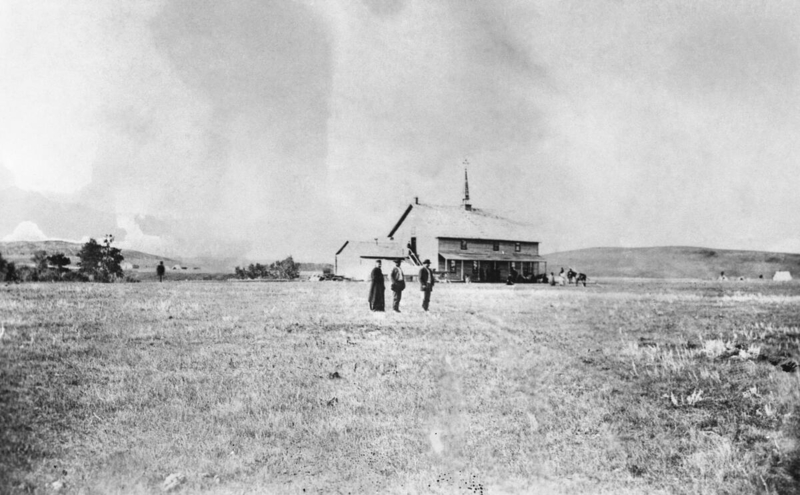

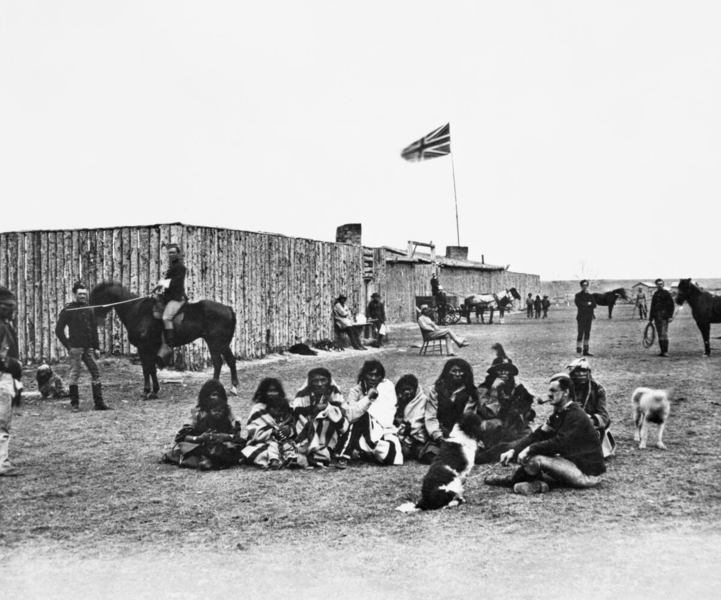

The following photos were taken during a trip to Fort Benton, MT:

Where to See This Era

Lac Ste. Anne Catholic Church, 3510 Ste Anne Trail, Alberta Beach, AB T0E 0A0

Father Lacombe Chapel Provincial Historic Site, 2 St Vital Ave, St. Albert, AB T8N 1K1

Rundle Mission National Historic Site, 47436 Range Road 15, Lakeshore Drive, Thorsby, AB T0C 2P0

Fort Edmonton Park National Historic Site, 7000 143 St NW, Edmonton, AB T6H 4P3

Victoria Settlement National Historic Site, 58161 Range Road 171A, County of Smoky Lake, AB T0B 0C0

Fort Whoop Up National Historic Site, 200 Indian Battle Rd S, Lethbridge, AB T1J 5B3

Old Fort Benton Museum, 1900 River St, Fort Benton, MT 59442, United States

Old Trail Museum, 823 Main Ave N, Choteau, MT 59422, United States

Fort Walsh National Historic Site, Maple Creek No. 111, SK S0N 0P0

Fort Macleod Provincial Historic Area, 239 24 St, Fort Macleod, AB T0L 0Z0

Galt Museum and Archives, 502 1 St S, Lethbridge, AB T1J 1Y4

Fort Calgary Historic Site and Confluence Parkland, 750 9 Ave SE, Calgary, AB T2G 5E1

Videos

Further Reading

William M. Baker, The Mounted Police and Prairie Society 1873-1919, 1998, University of Regina Press.

Stephen R. Brown, The Company: The Rise and Fall of the Hudson’s Bay Empire, 2020, Doubleday Canada.

Fort Calgary Audio Tour

Is there a list of people who lived at Fort Calgary in 1875-76 besides Inspector Brisbois and George King?