Welcome! The Calgary Heritage Initiative presents a series of articles throughout 2025 commemorating the 150th anniversary of the construction of Fort Calgary at the confluence of the Bow and Elbow Rivers, an important meeting place for people for millennia. Each month we’ll present one era in Calgary’s history.

Sign up to CHI’s newsletter and join us to explore the history and heritage of our region.

Calgary at War

South African War (1899-1902), World War I (1914-1918), World War II (1939-1945), Korean War (1950-1953)

Let’s take a break from the chronology of Calgary’s heritage and look specifically at the years when Canada participated in global conflicts. These wars had direct and indirect impacts on Calgarians.

To all those who have served to protect our freedom, we are forever grateful.

The Boer War in South Africa

The South African War (1899-1902), commonly referred to as the Boer War, took place almost 16,000 km from Calgary. On its own, the war was inconsequential to Calgarians, and yet it represents the evolution of geopolitical and economic affairs of the 20th century, when far away conflicts could and would be felt locally.

The Boer War has echoes of the Red River and North-West Rebellions/Resistances, when the British Crown and its government engaged directly with local forces. These conflicts occurred in part as a result of the creation of Canada.

In South Africa, the British sought the confederation of the British South African territories of Cape Colony and Natal with the republics of the Orange Free State and the South African Republic, which had been founded by the descendants of Dutch inhabitants, who became known as Boers and spoke Afrikaans. The Boers sought independence from British rule. When negotiations collapsed in 1899, the Boers invaded the British colonies.

The attack shocked the public throughout the British Empire. The UK and colonial governments mobilised forces from around the world, especially including Canada and Australia. 7000 Canadians volunteered for service, with 267 dying in the conflict. A total of 400,000 soldiers were involved against the Boer army of 88,000.

The conflict was ugly. As the war turned in favour of the British, the Boers used guerilla warfare tactics to undermine British control. In response, the British burnt farmland and rounded up Boers and black Africans in camps. About 28,000 Boers and 15,000 Africans, mainly women and children, died in the camps. The policy received widespread condemnation across the Empire and eventually was ended. Families returning home and cavalry skirmishes forced the Boers to end their guerilla war. Peace was negotiated and in 1910 the Union of South Africa was formed.

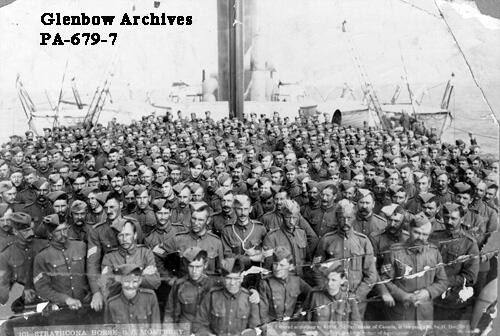

From London, Canadian High Commissioner Lord Strathcona, Sir Donald Smith, offered to raise money and equip a mounted regiment to serve in the war. The proposal relied on recruiting cowboys, homesteaders, and former NWMP officers across the prairies. Sam Steele, who had trained NWMP recruits prior to the March West in 1874, was given command of Stratchona’s Horse regiment. Training grounds for soldiers were set up at Victoria Park, at Currie Barracks and at Major Walker’s property (today’s Inglewood Bird Sanctuary).

The regiment was known for its expertise as scouts and one of its members received the Victoria Cross for bravery by rescuing a fallen soldier under a hail of gunfire. After the war, the regiment was disbanded. Major Walker went on to form the 15th Light Horse regiment and was promoted to the rank of Colonel.

As well, in honour of their service, King Edward VII awarded the title of Royal to the North West Mounted Police.

The federal government had planned to disband the force in 1896, but the Klondike Gold Rush required the police to enforce Canadian sovereignty and law and order in the Yukon. Their service to Canada at home and abroad led the government to maintain the force, which was eventually reorganized to create the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) in 1920.

The Horseman of the Plains

At Central Memorial Park, a statue commemorates the South African War. The memorial is nicknamed the Horseman of the Plains. Its creation paved the way for the other war memorials in today’s park, helping the park receive National Historic Site designation.

The soldiers returning from South Africa were celebrated as heroes. Yet the brutality of the conflict took its toll, with Albertan newspapers regularly reporting on the suffering of veterans, whether from social isolation, mental illness or unemployment. Locals organized relief efforts as well as commissioned a memorial. In 1911, local veterans and civic groups met with French-Canadian sculptor Louis Philippe Hébert, whose statues grace Parliament Hill in Ottawa.

He conceived a bronze sculpture to represent the Canadian prairie men who served, and those who never returned. The story that inspired the statue’s motif is tragic.

In 1909, a man was found frozen to death on the outskirts of Calgary, in today’s Killarney neighbourhood. The man was identified as a veteran of the Boer War who had volunteered to serve in Lord Strathcona’s Horse regiment. Calgarians donated for his funeral and his family in England returned the kindness with money for the memorial. Hébert suggested it be placed in Central Park, which was serving as a community focal point with the addition of the library.

When City Council first denied funding, the groups turned to women’s organizations and the boy scouts to organize fundraising to reach the $25,000 cost (about $600,000 today). Council eventually made up the shortfall and so Calgary was set to receive its first major commission of public art, the only equestrian statue by Hébert and his last major work. Because of the significance of the statue, Hébert wanted to get all the details correct, from uniform to saddle to Stetson hat. Pat Burns sent one of his ponies to Hebert’s studio in Quebec.

On 20 June 1914, the statue was unveiled in front of thousands of Calgarians. R.B. Bennet, federal MP for Calgary, delivered the dedication speech to all those who sacrificed and served and to all who would be inspired to serve.

The speech was inspiring but was also foreboding in retrospect, for only two months later, Canada was again at war.

First World War

Empires, alliances, royalty and an assassination brought Europe to war in August 1914. As in the Boer War, when the government in London declared war, it was doing so for its territories and domains, including Canada. 650,000 Canadians enlisted, with over 66,000 perishing in the conflict and 172,000 wounded.

Patriotic fervour reached fever pitch, with thousands of Canadians volunteering to fight for the British in Europe. Volunteers joined several regiments. One was Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry in Ottawa, named after Princess Patricia of Connaught, the daughter of the Governor General. Today the regiment is based in Edmonton and serves as the regular army regiment for Western Canada.

Princess Pat’s was the first Canadian unit in Europe and the men served in several significant battles, including Ypres, Belgium, at the Somme in France, and most famously at Vimy Ridge.

The British had been trying to take the Vimy hill top from the Germans, but failed, with the Germans occupying the high ground. Four Canadian divisions were sent to take on the German position, the first time they had fought together. Canadian soldiers trained meticulously on their advance, which was timed with artillery barrages. They were a rowdy bunch but they took orders well and trained hard for the mission, which was a success.

For his bravery and valour during the battle, Private John Pattison was awarded the Victoria Cross for rushing a machine gun emplacement (Pattison Bridge is named for him).

It’s said that men from across the vastness of Canada met in the trenches and on the battlefields of WWI, and together they made the soul of a young nation with their bravery, skill, dedication, and the ultimate sacrifice.

The Canadian National Vimy Memorial today stands on the hill top, a symbol of national unity that commemorates all those who served and who lost their lives in defence of Canada. The site is a preserved battlefield, with ordnance still present in the hill, with the memorial and its twin pillars towering over the landscape.

Other enlistees in the Great War who hailed from Calgary were Major Stanley Jones and his wife Lucille, who trained as a nurse with the Red Cross. He had served in South Africa and joined Princess Pat’s in 1914 as soon as war was declared, becoming the first Calgarian to sign up for service. He was injured in battle and taken prisoner, later dying in a German hospital in 1916. A city grateful for his service and sacrifice changed the name of Bridgeland school to Stanley Jones School in his honour.

Another enlistee was William Ware, the son of famed cowboy John Ware. He served in France as part of the No.2 Construction Battalion, an all-Black unit that was part of the Forestry Corps. At first, Black enlistees were rejected, until they forced the government to address their commitment to serve and reject racist assumptions.

The Construction Battalion was formed, one of the only battalions that recruited from across the country and was Canada’s first and only all-Black unit. It arrived in the Jura Forest of France in 1917 and began building logging roads and railways and sawing down and moving logs. Logging was essential to the war effort because wood was required for the construction of trenches, artillery platforms, railway ties, huts and bridges.

Many other Calgary units saw battle, including the Calgary Regiment, Southern Alberta Light Horse Brigade, and Lord Strathcona’s Horse.

Southern Alberta Light Horse was based on the Rocky Mountain Rangers during the 1885 Northwest Rebellion, an irregular light cavalry that patrolled the region. During WWI, several units were amalgamated, including Col. Walker’s 15th Light Horse. Some went on to fight the first tank attack in history, at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, while others were part of the last cavalry charge in Canadian history at the Battle of Iwuy.

Strathcona’s regiment had been revived as part of a mounted rifle unit in 1909. It was mobilized and sent to France as an infantry unit in 1914, but two years later were mounted and saw cavalry action on the Somme in 1917. One of “the last great cavalry charges” in history was engaged by Lord Strathcona’s Horse at the Battle of Moreuil Wood in 1918, for which three-quarters of the cavalry were killed or wounded by machine guns. Modern technology thereby ended a millennia-old battle tactic. After the war, the regiment was stationed at Mewata Armoury and eventually transitioned to motor vehicles.

A military camp at Sarcee leased from the Tsuu T’ina trained a total of 45,000 soldiers for war, the second largest training centre in Canada at the time. Dubbed Sarcee City, the tents were accompanied by a pool hall, bakery, cafe, theatre and shooting gallery.

In British tradition, before leaving for war the soldiers created rock art as a commemoration. In this case, the units placed 16,000 whitewashed stones in the pattern of their unit numbers on the side of a hill, which is today called Battalion Park, located on Signal Hill (formerly Cairn Hill). The 137th Calgary Infantry, the 113th Lethbridge Highlanders Infantry, the 151st Central Alberta Battalion and the 51st Canadian Infantry are commemorated.

During the war, a home for Calgary’s regiment was built. In 1906, federal lands for military purposes had been set aside to the west of the then downtown. In return, Mewata Park was donated to the city in 1906. In 1913, the city donated land for the construction of Mewata Armouries next to the park.

Built in 1917, it housed the Calgary Regiment, which continues today as the Calgary Highlanders and the King’s Own Calgary Regiment. Lord Strathcona’s Horse were also here, but overcrowding meant they moved to the new Currie Barracks in 1935. The structure is a fine example of armoury design, with medieval castle features, including buttresses with turrets, the crenellated roof line, and the tall gabled roof rising above the roof line. It’s built with red brick from Edward Crandell’s brick factory at Brickburn.

The First World War was even uglier than the Boer War. Trench warfare took a costly toll in human lives for very little territorial gain. The use of industrial military equipment made the battles gruesome affairs, and recovery for the injured and shell shocked was long and arduous.

Back at home, turmoil in world markets and bad weather depressed the price for Alberta’s commodities. Farms were debt ridden, schools were closed and communities faded away. Some abandoned their land altogether.

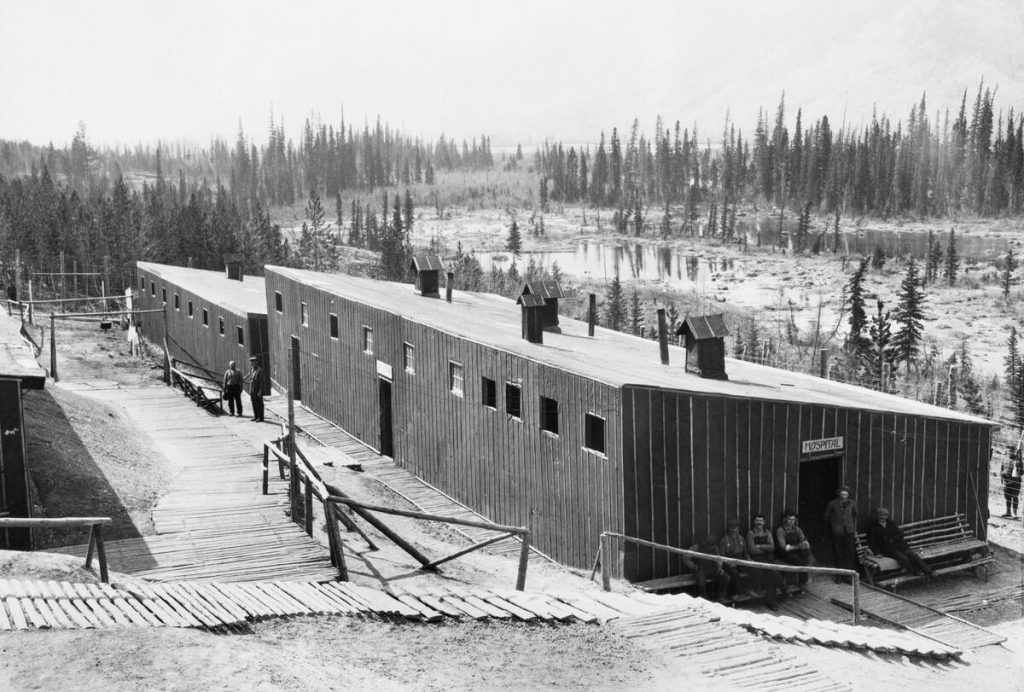

There was also strong suspicion of immigrants from the countries the British were fighting, which led authorities to establish internment camps at Castle Mountain, which was moved to Cave and Basin due to poor winter living conditions .

Ukrainians, Germans, Austrians and Hungarians were kept away from society to alleviate national security concerns, despite many having been in Canada for some time and part of Canadian society. They were guarded by soldiers from the Calgary Rifles regiment and were used as labourers to build roads in the park. Racial tensions sometimes broke out in Riverside, formerly Germantown, with brawls at Riverside Hotel reported by police.

Returning soldiers required care. A sanatorium was built in the Bowness area in 1918 to treat patients with diseases, which were being brought from overseas, including TB and Spanish flu. Today, Baker Park is named after the doctor who ran the facility, and it holds 1800 trees planted by the sanatorium’s gardeners (the building was demolished in 1989). Meanwhile, Stanley Jones School was turned into an emergency hospital from 1918-19 because of the influenza.

A residence of brickmaker Edward Crandell was used by the Red Cross from 1920-22 as the “soldiers’ children’s home”, which was for orphaned children and those convalescing after medical treatment. Crandell House was built in 1905 as a country retreat for Crandell and his wife Harriet. It’s an Arts and Crafts style cottage with wide verandahs because of its purpose and not surprisingly was built with red brick. Between 1951 and 1998, it was the home of renowned Stampede wrestler, Stu Hart.

A hospital for returning veterans was opened in 1919 in a renovated warehouse on 8th Ave SW. It was named after Lt. Colonel Robert Belcher, a charter member of the NWMP who died in the war along with his son.

In 1941, the federal government purchased the former mansion of Senator Patrick Burns as a convalescent hospital, with a new Colonel Belcher military hospital built by 1943. The mansion was demolished in 1956, with some of its sandstone used at Senator Patrick Burns Memorial Garden in Riley Park. In 1991 the Colonel Belcher was designated a long-term care facility exclusively for veterans of WWI, WWII and the Korean War. The facility moved in 2003 to 1939 Veterans’ Way NW. 3000 veterans are honoured on a wall at the facility.

Lest We Forget

The war’s toll was met with commemorations and remembrance in the years afterward.

In 1916 was formed a veterans mutual aid society, which joined with the national Great War Veterans Association and renamed the Royal Canadian Legion in 1961. In 1922 was built Memorial Hall, the headquarters of Calgary’s first branch of the Legion to house its meetings, community activities and to serve as a war memorial. It’s a Classical Revival style building with a restrained, symmetrical facade but has the flourish of round Roman arches. The Legion helped establish November 11th as a national day of remembrance in 1932, with its accompanying Poppy Campaign to raise funds for veterans in need.

In 1922, Memorial Drive was created as a “Road of Remembrance” to honour the soldiers who fell during WWI. Roads of this type were also created in Victoria, B.C., Saskatoon, SK, Thunder Bay, ON, and Montreal, QC as well as in the US, England and Australia. Their purpose is to memorialize soldiers with living trees rather than statues, symbolizing the triumph of life over death. Each tree along the drive was originally assigned to a fallen soldier, with 1699 trees planted by 1927.

Calgary Parks chose the location as it provides for a promenade that takes advantage of beautiful views of the city. Native poplar trees were planted in a way to give a natural feel to the parkway rather than in straight lines. Memorial Drive is Calgary’s only parkway. In 1990, a cairn was placed at 10th St NW to memorialize the veterans of past wars. Cuttings from the original trees were taken in 2001 to begin the process of replacement as they approach their end of life. The first new tree was planted in 2007.

In 1924, a statue of a soldier was erected by the Order of the Daughters of the Empire in front of Memorial Park Library to honour the soldiers of WWI. Then in 1928, a Cenotaph containing an empty tomb, dedicated to the memory of those who did not return to Canada from WWI, was erected near the South African Memorial in Central Park. 10,000 Calgarians attended the ceremony. At that time, the park received a new name, Central Memorial Park, in honour of its role for Calgary (a preexisting bandstand was subsequently removed). Then in 1930, a fountain was built in the park to honour the 50th Battalion’s role in the Battle of Vimy Ridge.

The Park played host to Remembrance Day ceremonies between 1928 and 1970, with the Cenotaph also remembering those who served in WWII, the Korean War, UN Peacekeeping missions, and the War in Afghanistan. Granite benches near the Cenotaph hold the inscriptions “May we live as nobly as they died”, and “Pass not in sorrow, but with pride”.

Leave a Reply