Welcome! The Calgary Heritage Initiative presents a series of articles throughout 2025 commemorating the 150th anniversary of the construction of Fort Calgary at the confluence of the Bow and Elbow Rivers, an important meeting place for people for millennia. Each month we’ll present one era in Calgary’s history.

Sign up to CHI’s newsletter and join us to explore the history and heritage of our region.

Booms and Busts

1967 to 1987

Calgary’s rapid growth has erased plenty of its past. In the 1960s and into the 1970s, downtown was transformed into a who’s who of skyscrapers linked by the +15 network. Gone were many of the original office buildings, railroad hotels and Calgary’s first homes.

Meanwhile, the city expanded into the surrounding prairies and foothills as it grew from roughly 350,000 people in 1967 to 625,000 in 1985.

Oil Sands

Development in Calgary after the Canadian centennial celebrations responded to the business of oil and gas. Previous booms and busts had left their mark, and the turmoil of the 1970s and the 1980s would be no different.

The petroleum industry in Alberta evolved from oil wells to oil sands. In northern Alberta can be found in the form of bitumen, a heavy, viscous form of petroleum. The area known as the Athabasca oil sands, named for the river which cuts through the deposit, is one of the largest sources of unconventional oil in the world.

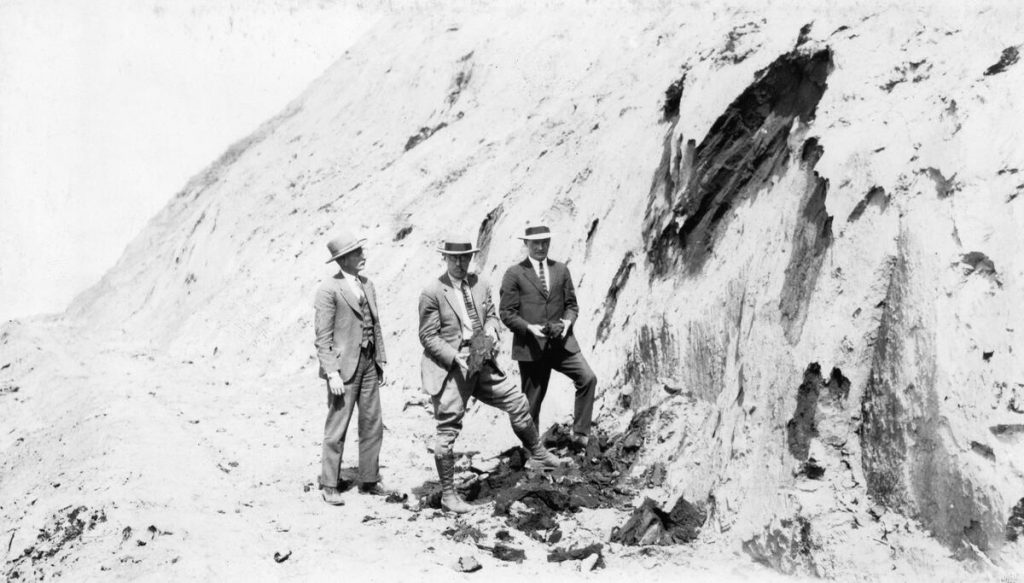

In history, surface bitumen deposits were used by the Cree and Dene peoples to waterproof their canoes. Fur traders and surveyors observed these deposits too. The government in Ottawa sponsored a survey of the area in 1875 and 1883. In 1888, the Geological Survey reported that North America’s, possibly the world’s, most extensive petroleum field may lie in the Athabasca and Mackenzie river valleys.

During WWII, the Alberta and federal governments sought to extract the oil sands deposits for the war effort, with mixed results. Premier Manning was undeterred given the potential of the deposit to bring prosperity to the province. His government supported development of the field after the war with experimental extraction and separation technology.

It took until 1962 for Sun Oil’s (today’s Suncor) subsidiary, Great Canadian Oil Sands (GCOS), to file an application for commercial operations in the oil sands. When the facility opened in 1967 in Fort McMurray, Manning performed the official opening for the largest private investment in Canadian history.

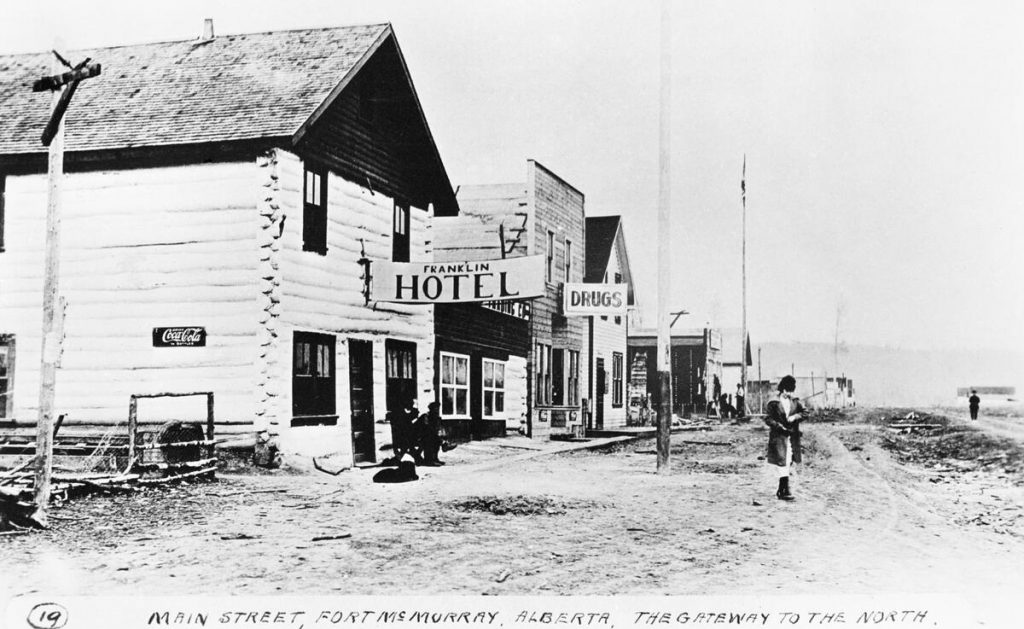

Fort McMurray was a HBC post in 1870 near an important junction on the fur trade route between Athabasca Country and the east. It was named after chief factor William McMurray. Several early efforts to separate the oil and refine it were established in the town, but these operations remained small until GCOS.

Geopolitics

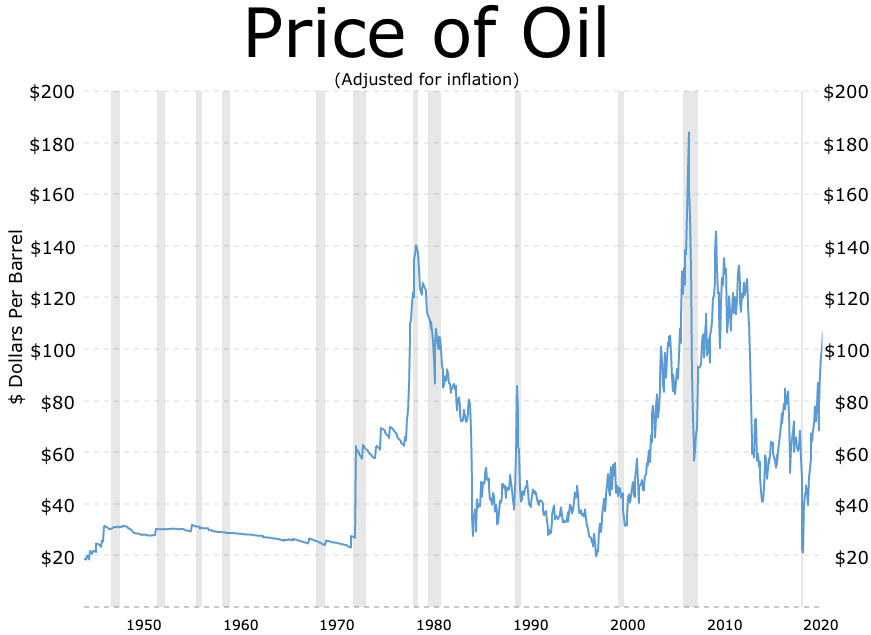

In 1978, Syncrude’s facility at Mildred Lake began operations. It had gone through many delays and financial uncertainty, which threatened its viability, that is, until the OPEC crisis in 1973.

On 6 October 1973, Israel was attacked by Egypt and Syria. Oil exporting countries, mostly Arab states, responded to the situation by preventing oil from being sold to Israel’s supporters in the West, including the United States and Canada. Oil prices rose by 300% in response to the embargo.

Western countries faced an energy and national security crisis. Their response was to develop as rapidly as possible their own sources of energy. In Canada, the federal government and the provinces of Alberta and Ontario agreed to rescue the Syncrude project by taking financial stakes in it. The plant initially produced 5 million barrels of oil within a year.

A second shock to oil prices occurred in 1979, perpetuating another energy crisis in Western countries. The Iranian Revolution caused the oil price to double over the course of the year, with further instability caused by the Iran-Iraq war. Fuel shortages were experienced just like in 1973.

National Politics

The commodity price cycle has its benefits and also its risks, which Calgarians faced directly.

The energy crisis in the 1970s ed to further development in Calgary. By 1981, 45% of the labour force in Calgary was manager and office staff, which was above the national average of 35%. When the oil price glut hit in the 1980s, the local economy took a nosedive. Energy policy disputes within Canada also had their consequences.

When oil prices skyrocketed in the 1970s, the benefits to Canada were heavily regionalized. Alberta benefited from high oil prices and more investment while consumers and industries in central and eastern Canada paid higher costs.

The government in Ottawa sought to correct these imbalances. When price volatility and inflation reemerged during the second energy crisis, the federal government developed the National Energy Program (NEP).

The NEP was created by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau to price energy within Canada and provide for energy self-sufficiency, which included Canadian ownership in the energy sector, more exploration, and promoting energy alternatives. Ottawa relied on its power to regulate trade and commerce in the oil and gas industry. Setting a Canadian energy price different from the price on world markets meant using price controls.

The federal program kicked off a constitutional crisis.

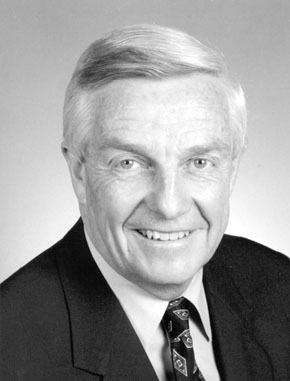

Alberta Premier Peter Lougheed was an active opponent of the NEP. He argued it infringed on provincial jurisdiction to develop resources and enjoy the royalties derived from sales of natural resources.

Lougheed was also a proponent of conserving natural resources for the future benefit of Albertans. He sought better management and environmental policies along with sustainable development. He also used the inflow of royalties to improve public institutions, including social services and the province’s heritage and culture.

The imposition of the NEP against Lougheed’s wishes led him to announce a cut to oil production in the province. The NEP’s goal of lowering prices within Canada was nullified by the production cut. These moves forced critical federal-provincial negotiations.

In 1981, a revenue-sharing agreement was struck. Then in 1982, constitutional changes were agreed, with section 92A clarifying and elaborating on provincial control over non-renewable resources. The NEP ended after Brian Mulroney’s Conservative government was elected in 1984.

Part of the federal government’s effort to deal with the 1973 energy crisis led to the creation of Petro-Canada. In 1975, the Crown corporation was established to invest in energy projects, including Hibernia oil off the coast of Newfoundland and it partnered on the Syncrude project. It also invested in a new office tower in downtown Calgary.

Petro Canada Centre (today’s Suncor Energy Centre) is composed of two Finnish granite and glass office towers, of 52 and 32 floors each, which opened in 1984. The taller west tower was the first to overtake the Calgary Tower, becoming the tallest building in the city at the time. Because of the controversy regarding federal energy policy, it was infamously called “Red Square”, referencing the famous central square of Moscow, which was then under Communist rule.

The moniker was associated with a major downturn in development in Calgary at the time. In 1979, more office space in Calgary than in New York City and Chicago combined. By 1984, when the towers opened, the recession was palpable. Unemployment in Alberta had reached 12.4% and bankruptcies jumped 150%.

The City of Calgary laid off 400 people, with the city’s unemployment peaking at 15%. The slump was so swift, Calgary’s population decreased for the first time in its history. There were 3331 home foreclosures in 1983. The economy remained sluggish into the 1990s. Nevertheless, Alberta was a changed place. By 1986, there were half as many farms on the prairies than in 1941.

The Core

The downtown core added many other towers before the 1980s’ bust. These developments put Calgary on a path to having the highest concentration of skyscrapers in CAnada outside downtown Toronto.

One Palliser Square was completed in 1970, a 27-storey office tower and part of Tower Centre linked to the Husky Tower. It houses two theatres and is being refurbished to include residential units. The Tower was renamed to the Calgary Tower in 1971 when Husky Oil sold its share in the complex. The rename was and remains a tribute to the residents and history of Calgary.

In 1976, the 41-storey Scotia Tower was built for the Bank of Nova Scotia’s offices. Today it’s called Stephen Avenue Place and houses a restaurant on its 40th floor (the view with dinner is fantastic!).

In 1977, Toronto-Dominion Square was erected, originally called Oxford Square. It’s a complex with a 5-storey base and two 35-storey towers. The south tower was named for Home Oil and the north for Dome Petroleum. Anyone visiting St. Paul, MN will see a familiar set of towers at Tower Square.

Inside the complex is Devonian Gardens, a large indoor park with skylight and botanical garden. It holds a living wall, koi fish ponds, a play area and 550 trees. The park was donated to the city and cost $9 million ($41.5 million today).

Devonian Gardens occupies the top floor of The Core Shopping Centre. Formerly called TD Square, it’s the largest shopping mall in the downtown core. It spans three city blocks and connects to six office towers, with the +15 system linking it to 5 other centres. In 2011, the Core underwent major redevelopment, which included the installation of the world’s largest point-supported glass skylight at 200 metres long.

Across the street from the TD Square towers, the same designer worked on First Canadian Centre. This project was intended to have 41-storey and 64-storey towers. But because of the 1980s recession, the taller tower was never built. The tower that was completed in 1982 is in the International/Late Modernist style, with Italian white-grey marble cladding. At night, police stopped traffic to facilitate North America’s largest continuous concrete pour at the time.

Another modern building to mention is the NOVA Building (today’s Nexen Building). It’s a 37-storey building in the late Modernist style, which is most evident since it’s the proverbial glass office tower. It was completed in 1982 and is one of the few buildings in downtown Calgary to stand diagonally, so neither facing north-south or east-west.

It housed the headquarters of NOVA (today part of TC Energy), formerly the Alberta Gas Trunk Line Company. Premier Manning established the company in 1954 to link up the province’s cities and towns with natural gas, one of the largest pipeline infrastructure projects in history. After sitting mostly empty for a time, it will now house the UofC’s School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape.

Calgary’s downtown became the backdrop for Superman III starring the late Christopher Reeves. In 1982, several exterior scenes were filmed in Calgary, which doubles as Metropolis. Superman is shown drinking, which was filmed at the St. Louis Hotel in East Village. High River, AB doubled as Clark Kent’s hometown, Smallville, KS.

Downtown’s expansion upward meant that the areas immediately around it were also up for change.

In 1972, Bow Valley College received a new location for students and teachers. The College began in a basement at SAIT in 1963 when adult students attended upgrading classes, which at the time was referred to as vocational training. These classes enabled them to fill gaps in their education and go on to fulfill their career or learning goals.

In 1965, the Alberta Vocational Centre was officially founded. It expanded to offer English education courses and certificates in all kinds of career fields. By 1990, the College was serving 6500 full-time and 15,000 part-time students. In 1998, it changed its name to Bow Valley College to reflect the region it serves and expanded its campus in recent years, becoming an anchor for downtown’s east side.

Nearby was built a new City Hall. In 1985, the Calgary Municipal Building was completed just behind the Old City Hall. A proposal for a new municipal complex with hotels and parks was voted down by Calgarians in 1979. The next mayor, Ralph Klein, garnered public support by proposing a new city hall as a cheaper alternative to renting private office space across 10 different buildings.

The design of the building was controversial, called a monstrosity by some. The glass, tiered building was designed to contrast the Old City Hall and use it as a backdrop for the national historic site. Limestone panelling on the lower walls reflects the older building’s design. City Council itself is housed in a blue cube on the main floor. A time capsule was installed in the building, to be opened in 2084.

Speaking of government buildings, in 1978, the federal government’s new office block was completed along the Bow River. Demolition of residences in the area began in 1974, relocating 180 from Calgary’s Chinese community. During excavation for the site, over 1000 bison bones were uncovered.

The building holds offices and a public service mall and atrium. It was designed with setbacks on the upper floors to transition from the Bow River to the high rises next to it. It was named in honour of Harry Hays, unusual since he was still living at the time.

Hays was from Carstairs, AB though his family originated in Missouri. He was a successful farmer and led a WWII effort to increase food production, a campaign called “Bacon for Britain”. He served as mayor of Calgary after two elections in 1959 and 1961. He went on to federal politics and served as Minister of Agriculture and then as a Senator. The dairy farm he sold to fund his first campaign was located on what is today known as the community of Haysboro. He died in 1982.

Just to the west of the Harry Hays Building is Eau Claire. Calgary Transit’s bus barns at Eau Claire opened in 1947, replacing the streetcar barn in Victoria Park. They were then closed in 1984 and moved out of the core. The area next to Prince’s Island Park was envisioned as a festival market, akin to Vancouver’s Granville Island, with restaurants, public market and shops. Edmonton had a lesson for Calgary, since it converted its old bus barn into the popular Old Strathcona Farmers’ Market.

Yet Eau Claire failed to grab the attention, and feet, of Calgarians.

Eau Claire presents a lesson in heritage preservation. Granville Island and Edmonton’s market kept and integrated their older buildings into new uses.

Calgary’s direction for Eau Claire was to construct an entirely new building on the site. The building had its back to the downtown, cutting it off from the river. Meanwhile, the market itself was imposing and bland, with its open outdoor square built away from the river pathways. The heritage buildings that did remain on site, the transit barn’s smokestack ca.1947 and the saw mill’s office building, were afterthoughts.

All this meant Eau Claire Market never captured the imagination of Calgarians. Development was also curtailed because of the recession, with the bus burns sitting empty for 4 years until they were demolished in 1988. Unlike what most Calgarians did, we’ll revisit Eau Claire Market in next month’s article.

Speaking of heritage preservation, Calgary’s rapid development in the middle of the 20th century created some difficult situations.

The old Calgary General Hospital #2 from 1895 had served as Rundle Lodge, a seniors’ residence run by the United Church, when its last remaining hospital service ended in the 1950s. In the early 1970s, the city condemned the building as no longer usable and scheduled it for demolition.

A preservation society formed to try to save the building. However, the province was not forthcoming with heritage protection or funds to restore it, and it was demolished in 1973. Some of the sandstone ruins on the site were preserved however, and turned into a park, called Rundle Ruins.

The hospital complex in Bridgeland-Riverside also changed in the 1970s. The School of Nursing closed its doors and transferred to the University of Calgary. It ran for 79 years and graduated almost 3000 nurses. The University of Calgary’s Faculty of Medicine has gone on to facilitate medical education, including establishing the first family medicine program west of Toronto. The Gertrude M. Hall Education Wing was built in 1970 to accommodate this program.

Hall had been recruited by the head doctor at the CGH for her renowned work as CEO of Manitoba’s Nurses. In taking up the position of CGH’s Director of Nursing, she turned down the post of Chief Nurse for the World Health Organization. Hall later resigned her position in support of quality healthcare during a budget cut dispute with City Hall. She died of a heart attack on stage during the graduation ceremony of her last nursing class on 14 October 1960.

Despite the loss of the nursing school, CGH #4 attracted many other healthcare facilities, further transforming its surrounding neighbourhood. These included the Canadian Institute for the Blind, Bow Valley Seniors Housing (now the Silvera Bow Valley, Aspen, Spruce, and Willow Park Communities), the Rehabilitation Society of Calgary, the Bridgeland Seniors Health Centre, and the Crossbow Auxiliary Hospital (which opened in 1961 and closed in 2004).

Another centre opened in 1969, the Carewest George Boyack, where I went as a child to visit my grandparents during their last years. A new Bridgeland Riverside Continuing Care Centre is currently under construction, maintaining the neighbourhood’s proud tradition of hosting lifegiving healthcare.

Connections

A larger downtown meant infrastructure was needed even though the grand plans from the 1960s did not come to fruition.

With Chinatown and Inglewood fighting against the Downtown Penetrator, a portion of the north side of the Bow River was saddled with the new corridor into downtown. Calgary’s longest bridge opened in 1982 when the 4th Avenue Flyover was built to get traffic into downtown. It connects the downtown to the part of Memorial Drive that was built into a freeway heading toward Deerfoot Trail. Its construction meant cutting into the Bow River embankment that is today’s Tom Campbell’s Hill Natural Park.

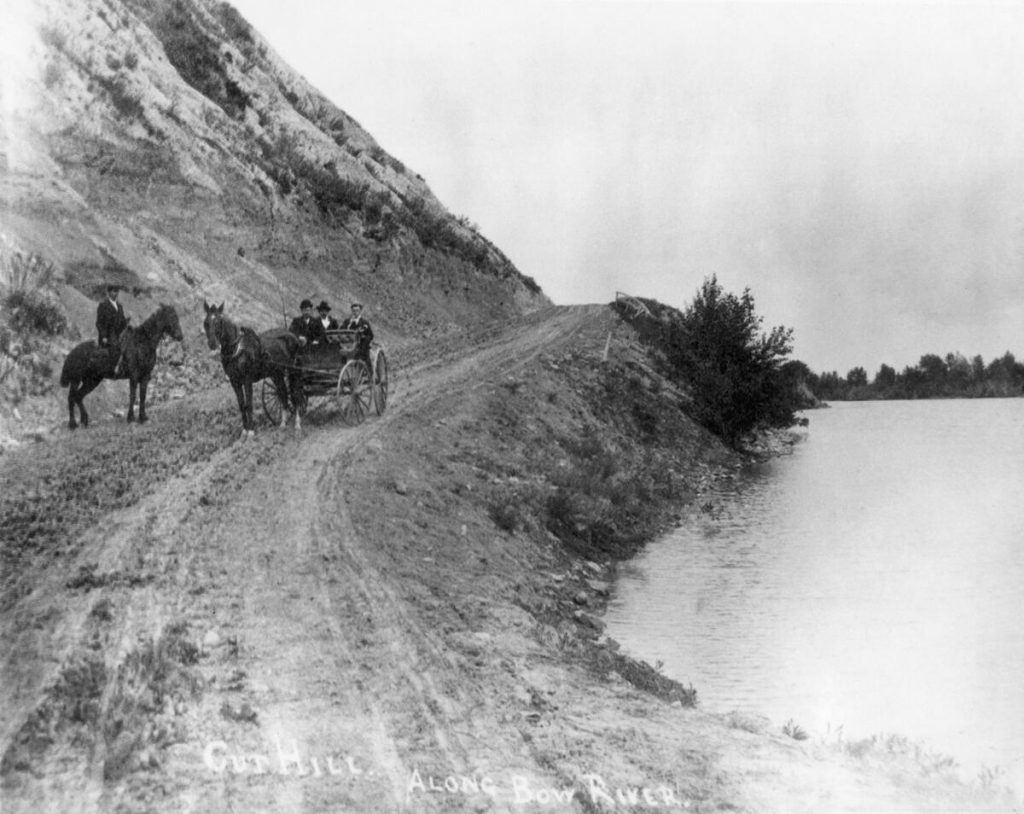

Tom Campbell’s Hill is the end point of the embankment that follows both the Bow River and Nose Creek along their courses through Calgary. It became ranchland and then for a couple decades the Calgary Zoo kept hoofed animals up there.

At one point it was slated for development, but local residents fought for a park instead, which was established in 1991.

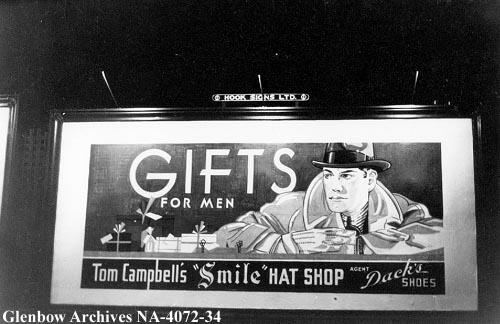

It received its name from a sign that used to stand on the hill and advertise for Tom Campbell’s Hats, a men’s hat shop dating back to 1910. It’s now a natural area, with rough fescue, Alberta’s official grass, found throughout it along with native flowers, including avens and moss phlox.

It wasn’t the first time Bridgeland-Riverside underwent changes to accommodate access to downtown.

Today’s Edmonton Trail was created in the 1970s when 4th St NE was made into a one-way street southbound into the core. 5th Street was then widened to create a northbound road that connects to the 5th Avenue Flyover leading out of downtown.

In between the two streets is an area called the Couplet, which is a bit of a misnomer since the thoroughfare cuts a part of western Riverside off from the rest of the neighbourhood. The area west of the 4th St is today part of Crescent Heights.

Let’s finally get to Deerfoot Trail, that wonderful, efficient, pleasant (not!) expressway that winds its way parallel to Nose Creek and then the Bow River. It’s Calgary’s first freeway, meaning there are no traffic lights on it, though there certainly are lights at its various interchanges.

Prior to its completion, Highway #2 ran south along Macleod Trail and north along Edmonton and Barlow Trails. The north section was realigned to follow Macleod until Glenmore eastbound and then proceeding on Blackfoot Trail. The winding nature of these thoroughfares through Calgary, with so many traffic lights, meant it was increasingly insufficient as a transport route through the city, especially after the post-war boom.

Plans for a major freeway system across the city and into downtown were rejected yet the north-south leg of the planned system, today’s Deerfoot Trail, was actually built. The first section was completed in 1971 and stretched between 16th Ave NE and the north city limit at Beddington Trail. It was originally called the Blackfoot Trail Freeway.

There was opposition from Premier Lougheed about the southern leg, which would originally cut through Fish Creek Park. A revised alignment was developed that moved the freeway 1 km east along the present-day communities of Douglasdale, McKenzie Towne and Lake.

Douglasdale was developed from 1986 and borders the Bow River as it courses through Fish Creek Provincial Park (see below). Its development has proceeded northward over the years, most recently at Quarry Park.

This area used to be a gravel extraction site until 2005, when it was slated for development as a mixed-use neighbourhood with residences, green space and corporate offices. Engineers studied low-lying areas in the Netherlands when designing the berm that can withstand a one-in-100 year flood event. They also installed overland canals to divert and filter water.

McKenzie Lake community was developed in 1982. It’s named for John McKenzie, who arrived from Montreal and homesteaded the area in 1882. It includes a manmade lake, which was added to the original community given the popularity of nearby Bonavista Lake. This community was started in 1967 and was the first in Canada to be built around a manmade water feature.

Nearby McKenzie Towne is a master planned area, built starting in 1995. Referred to as a neo-traditional community, it was meant to reflect a small town, complete with high street, everyday services, and mix of residential and apartment buildings in various styles. It was based on the designs of the new urbanist movement, which are best characterized by the layout of Seaside, FL, where The Truman Show was filmed.

The southern half of Deerfoot opened in segments between 1975 and 1982. In 1980, it went as far south as Glenmore, finally replacing Blackfoot Trail as Highway #2.

This section includes the Calf Robe Bridge over the Bow River. The Bridge was named in honour of Ben Calf Robe and his role in founding the Stampede (see June’s article). The bridge is notorious for accidents since its curvature over the river and proximity to Bonnybrook wastewater treatment plant generates slippery conditions. The problem was so common that Indigenous elders were asked to tend to the bridge with ritual song and dance to remove any “curses”.

Deerfoot’s last segment was extended in 1982 to Highway 22X, formerly Marquis of Lorne Trail and now part of Stoney Trail. Because it avoids Fish Creek, part of the old alignment became Bow Bottom Trail, which ends at Fish Creek. Highway # 2 was now Macleod Trail to Anderson Road to Deerfoot.

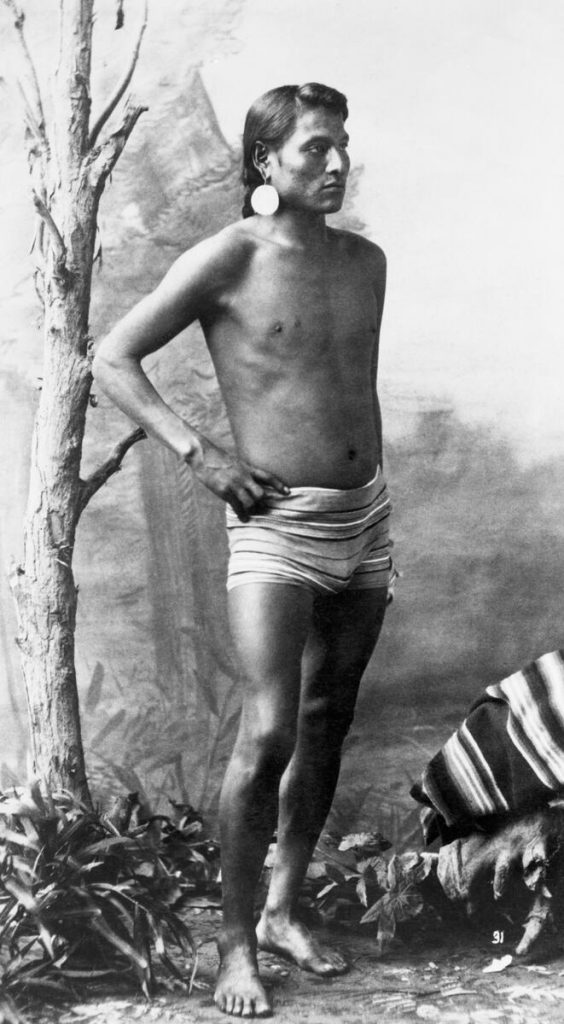

In 1974, the freeway was renamed in honour of a Siksika Nation man. In 1884, Api-kai-ees (“Scabby-Bad Meat”), the nephew of Chief Crowfoot, became famous for winning the 1886 Dominion Day 1 mile race. He was within one second of breaking the world record for that distance.

Deerfoot was a messenger for the Blackfoot Confederacy, running between camps in Alberta and Montana. He also competed in local races, where he gained a following. When the Star-Rink indoor track in Calgary was built, it hosted championship foot races. Calgarians at the time enjoyed betting on these races, and many cheered their local hero, called Deerfoot in English.

In one match, he won but his European opponent was declared the winner on a supposed technicality. A rematch was held and Deerfoot won. Nevertheless, he became disillusioned with competing because it was associated with gambling and corruption. He spent time in and out of jail in his later life and died of tuberculosis at the age of 33. His athletic prowess and travels across Alberta are remembered in the name of Calgary’s first freeway.

Not only the highway system but the airport too continued to expand during this time. Another terminal building opened in 1977, meaning Calgary could now handle jumbo jets, such as the Boeing 747. The terminal was delayed by several years because of redesigns to meet the demand of increasing air traffic. Calgary received non-stop 747 flights with service to London in 1973, with many more international routes added since.

The celebration to open the new terminal was attended by the arrival of British Airways’ newly-introduced Concorde aircraft, the first commercial jet to travel faster than the speed of sound. The Canadian Air Force Snowbirds also did a flyover. The terminal today handles most domestic air travel.

Back on the ground, the city was contemplating a rail transit system to accompany the new downtown freeways. Even though the freeway plans were drastically altered, the plan to turn 7th Avenue into a dedicated rail transit corridor continued, though with light rail rather than heavy rail. It had been thirty years since the city operated a rail system. The last streetcar stopped service in 1950, replaced first by electric trolleybuses and then with diesel buses.

The C-Train system opened in May 1981, with construction beginning in 1978. The original line ran from Anderson Station in the south to 8th St SW in the downtown core – this was the first version of the Red Line. Oliver Bowen, a descendant of Black settlers from Amber Valley, AB, managed the design and construction of the original C-Train. The Oliver Bowen Light Rail Vehicle Maintenance Facility is named in his honour.

In 1985, a northeastern line was completed, running from 10th St SW along 7th Avenue to Whitehorn Station – this was the original Blue Line. The next phase of the C-Train was completed two years later when the northwestern line was completed to the University of Calgary (just in time for the Olympics – see next month’s article).

Flames

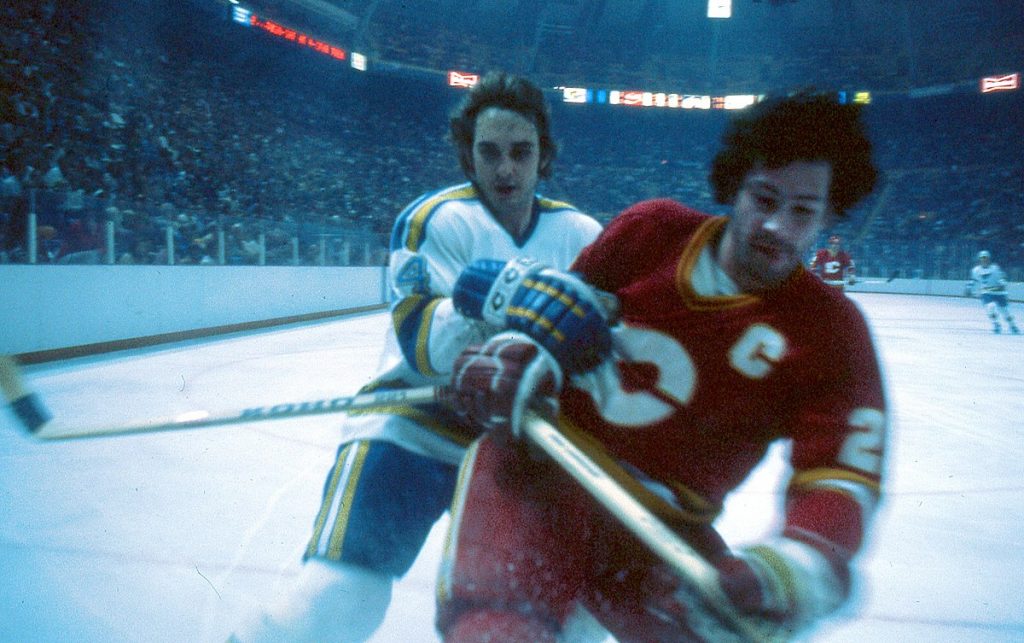

One reason to have a C-Train, besides the daily commute to downtown, was to get people to the new Saddledome to see a hockey game.

One era of the NHL begins with the Original Six teams – Boston, Chicago, Detroit, Montreal, New York, Toronto. They played between 1942 and 1967. In that year, six more teams were added to the league, in L.A., Minnesota, Oakland, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis.

Canadians were irate at the lack of additional Canadian teams. A new league was established, the World Hockey Association. It was established in 1971 specifically to serve the demand for hockey in markets not served by the NHL. The two leagues competed for the best talent, which the WHA succeeded when it brought over star forward Bobby Hull. It also attracted European players to North American for the first time.

In reaction to the WHA, more teams were added to the NHL in 1972 and ‘74. In ‘72, the Atlanta Flames were added along with the New York Islanders. The team name “Flames” was chosen by the franchise owner to honour the burning of Atlanta’s infrastructure in 1864 during the U.S. Civil War.

In ‘79, the NHL and WHA merged, which brought Edmonton, Winnipeg and Quebec City into the NHL.

Atlanta had its best season in ‘78-’79, with 41 wins to 31 losses. However, they never made it past the first round of the playoffs. Attendance suffered as a result, peaking at 14,161 fans on average in ‘74, falling to 10,000 in ‘80. With the owner also in financial difficulty, the team was put up for sale. Houston or Dallas were potential destinations, but Calgary led the pack.

A consortium of oil men and real estate magnates led by Nelson Skalbania put together an offer. The consortium included the Seaman brothers (Doc was a former RCAF pilot, and my father worked at his company, Bow Valley Resource Services), Harley Hotchkiss (who later donated to the Brain Institute), Ralph T. Scurfield, Norman Green, and Norman L. Kwong (a former Calgary Stampeder who went on to become Lt.-Governor of Alberta).

They paid US$16 million ($61 million US today) for the franchise, a record price at the time, with the city preparing for the construction of a new stadium. And they kept the Flames name, since the consortium thought it also made sense for an Oil Capital (think of all the well blowouts that occurred in the early days of oil and gas exploration).

In the meantime, the Flames played at the Stampede Corral. They were instantly successful, with 10,000 ticket packages sold for the 7,000 seat Corral. The team entered the playoffs from the get go, beginning a playoff attendance streak that lasted until 1991.

Their success kicked off one of the deepest-felt rivalries in professional sports.

In 1984, Calgary took Edmonton to game 7 in their playoff round, but lost. Between 1984 and 1991, the Flames roster reached 90 points every season but one. But the Cup was out of reach mostly because of Edmonton. Between 1983 and 1990, either the Flames or the Oilers represented their conference in the Stanley Cup finals.

The 1985-6 season saw the coming together of Lanny McDonald, Al Macinnis and Mike Vernon, among others, including Gary Suter and Joel Otto. They took Winnipeg down in the first round of the playoffs and Edmonton in the second. They barely defeated St. Louis, advancing to their first Stanley Cup finals. However, they lost to the Montreal Canadiens and the goaltending genius of Patrick Roy.

In 1987-88, the Flames had their best regular season yet, topping 100 points for the first time. This earned them the Presidents’ Trophy and the added benefit of dethroning Edmonton’s six-year reign. Joe Nieuwendyk became the second rookie in NHL history to score at least 50 goals in a season that year. A run for the Cup was all but guaranteed, but Calgary lost to Edmonton in four straight games. Would they ever win the Stanley Cup? Find out next month.

The Flames moved into the Saddledome in 1983. It originally held 17,000 seats and cost almost $100 million ($285 million today). The Corral had been deemed insufficient for an NHL team in 1977, prompting the WHA’s Calgary Cowboys to fold. The purchase of the Atlanta Flames and Calgary’s bid for an Olympic Games helped get support for the city to construct a larger arena.

The location was chosen by City Council after considering a site near Airdrie and on the west side of downtown. Its current location wasn’t without controversy, since Victoria Park Community Association opposed the development. In the end, the planning regulations were overruled by the province and construction began. It also was not lost on officials that getting shovels in the ground could help with Calgary’s bid to host an Olympic Games.

The building is iconic in terms of stadium designs and is instantly recognized, particularly after being shown to the world during the 1988 Winter Olympic Games. However, a western theme was not part of the designers’ intention. Rather, they wanted to build a reverse hyperbolic paraboloid roof for the building (think about the shape of a Pringles potato chip). The shape allowed for a view of the ice rink free of any pillars, and it was capable of being flexible, something necessary given Calgary’s fast fluctuating weather patterns.

Despite the technical reasons for the roof’s shape, Calgarians were quick to see a horse saddle in the design, and the name Saddledome has stayed with it ever since. It’s a fitting name for both our Stampede City and the Stampede grounds on which it was built. Some noted at the time that the arena isn’t even a dome, but nevertheless, the Olympic Saddledome gained notoriety. The designers were honoured by the Royal Architecture Institute of Canada and the ‘Dome featured on the cover to Time magazine on 27 September 1987.

The Saddledome’s opening on 15 October 1983 boosted the morale of a city still experiencing a recession caused by the oil price glut. Its first event was a hockey game between Calgary and Edmonton, which Calgary lost.

The Saddledome retains the record of the world’s largest concrete reverse dome, and it was the first rink in North America designed to accommodate the larger ice surface for international hockey, which are 15 feet wider than NHL regulation rinks.

The Saddledome is currently scheduled for demolition to make way for a new arena. It’ll mark a drastic change to the city’s skyline. If you’ll allow me to take a personal moment, I will greatly miss the Saddledome as an iconic representation of our city. There are currently no plans to remember the aesthetics of this unique arena, and the new facility will be modern and free of any western themes, at least to my eyes.

I predict we will miss the ‘Dome when it’s gone, and so I hope Calgarians find a way to remember its role in shaping Calgary into an international city, an issue I’ll discuss in greater length in December’s article.

Leave a Reply