Oil Capital

1945-1967

Parks and Recreation

Calgary’s natural beauty is an integral part of the city, though not without some effort on the part of Calgarians to secure park and natural spaces as the city expanded during the boom times.

To commemorate Senator Patrick Burns, a memorial rock garden was landscaped in 1956 on the slope south of SAIT campus. The garden was designed by Alex Munro, Parks Superintendent from 1949 to 1960. Like Reader, Munro had a gardening column in the Herald and sought to share information about Calgary horticulture.

Rock gardens became popular in England in the early 1900s as a move away from the highly sculptured landscapes of Victorian gardens to more naturalistic styles. The Burns garden uses over 20,000 sandstone blocks from the Burns mansion, which was demolished in 1955 to make way for the Colonel Belcher Hospital expansion. It also uses local alpine plants, such as highbush cranberry, juniper, pine and snowy mountain ash. The slope on which the garden is laid is perfect for this kind of landscaping, providing the contouring for its naturalistic style when the slope would otherwise be difficult to use.

The Zoo received a hallmark building in 1962. The Conservatory, later renamed the Tropical Aviary, is a steel-glass structure built at the central point of St. George’s Island. It contains three interconnected greenhouses, which allows for each area to portray a different climatic zone. Personally, I love looking at all the different cacti in this exhibit.

Recreation development also took place along Calgary’s edges at the time. In the mid-1950s, residents in Calgary’s north sought the creation of a sports facility in their area. In 1957, land was purchased on 14 St NW along the incline up to Nose Hill. It was used to build a sports complex, to which memberships are sold for $500 ($5400 today). In 1960, the Winter Club opened with 8000 members and includes all sorts of indoor sports.

On the other side of Calgary, River Park on the west side of the Elbow River, and Riverdale Park on the east side, developed. A bridge to connect them was sought in 1928 and again in 1945. River Park hosted YMCA day camps as well as Calgary’s first day camp for disabled persons. In 1955, the park was acquired by Eric Harvie, who sought to establish an area for rest and relaxation in a natural setting. Its former use as a ranch and agricultural lands was perfectly suited for this kind of park.

Around this time, Britannia neighbourhood was before the city’s planning department. It is Calgary’s first fully planned neighbourhood, with commercial plaza, residences and community institutions and parks laid out. Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation in 1952 inspired its naming, including royal-themed street names, which the Royal couple toured in 1959.

Britannia was also the location of Trend House, one of 11 innovative “Homes of Tomorrow” built across Canada between 1953 and 1954.

In Calgary, Trend House was a prototype for Prairie Modernism and showcased Canadian softwood lumber home building material. A public open house was held for several months in 1954, with interior design provided by Eaton’s and appliances by General Electric. It pioneered an open plan concept, with exposed Douglas Fir beams and Western Red Cedar panels. It became a provincial historic site in 2018.

Britannia Plaza was designed around a London town square layout, which inspired other outdoor promenades, including Cambrian Heights, Haysboro, Mayland Heights and the now-demolished Stadium Shopping Centre.

At Mayland Heights was constructed a Safeway (today’s Family Foods), which was built to serve the northeast’ growing communities.

The store is in Safeway’s Marina style, a corporate design built across Canada and the U.S. It incorporates the Expressionist style of the time, and is now rare today. It’s a rectangular building with an iconic gull-wing roof and white rubberstone walls on its front face.

Another neighbourhood landmark is the Firestone water tower. It’s representative of the industrial growth of the city during this Oil Capital era. Firestone was expanding internationally because of the automobile craze and chose Calgary for the site of a tire factory.

Another important example of Calgary’s manufacturing economy is the Inland Cement Industries Office Building. It’s an Expressionist style building constructed in 1963. Its theatrical saddle-style roof dominates over a glass curtain wall and is anchored by large concrete piers. It was the first major development in the Foothills Industrial Estate, with the company operating four concrete plants across the prairies.

The neighbourhood of Altadore was also being planned at the time, so connecting them via a pedestrian bridge finally won the day.

Eric Harvie worked with the city to set aside parkland along the river and up the escapement, calling it River Park, which includes Sandy Beach Park. He also donated $100,000 for the park’s infrastructure. Finally, in 1959, the River Park Suspension Bridge was built, only one of four suspension bridges in the city. The original bridge did not survive the 2013 flood and was replaced one year later.

Calgary also received a new park to celebrate Canada’s centennial. In 1965, the coulee along a creek that runs off Nose Hill was proposed for a park. The Centennial Ravine Park Society formed to advocate for its development, with funds raised from Calgarians. This was during a time where civic activism and environmental awareness had caught the public imagination.

Harry Boothman, Parks Superintendent, embraced the effort and passion of Calgarians with this planning theme “Parks are for People”. Confederation Park emerged from these plans. Every year, a garden is planted in the form of the centennial symbol, and the flags of Canada and all provinces and territories are proudly displayed on 10th Street.

The park was formed around the coulee and intermittent creek and integrated them with the surrounding communities. Its design reflects the trend away from ornamental, decorative parks and toward a more natural, unstructured park experience. It incorporates concepts from the picturesque, landscape style that originated in England in the 1700s as well as the need for storm water management, a unique innovation at the time. The coulee is designed to flood during major rainfall, and thus control the amount of water entering Nose Creek.

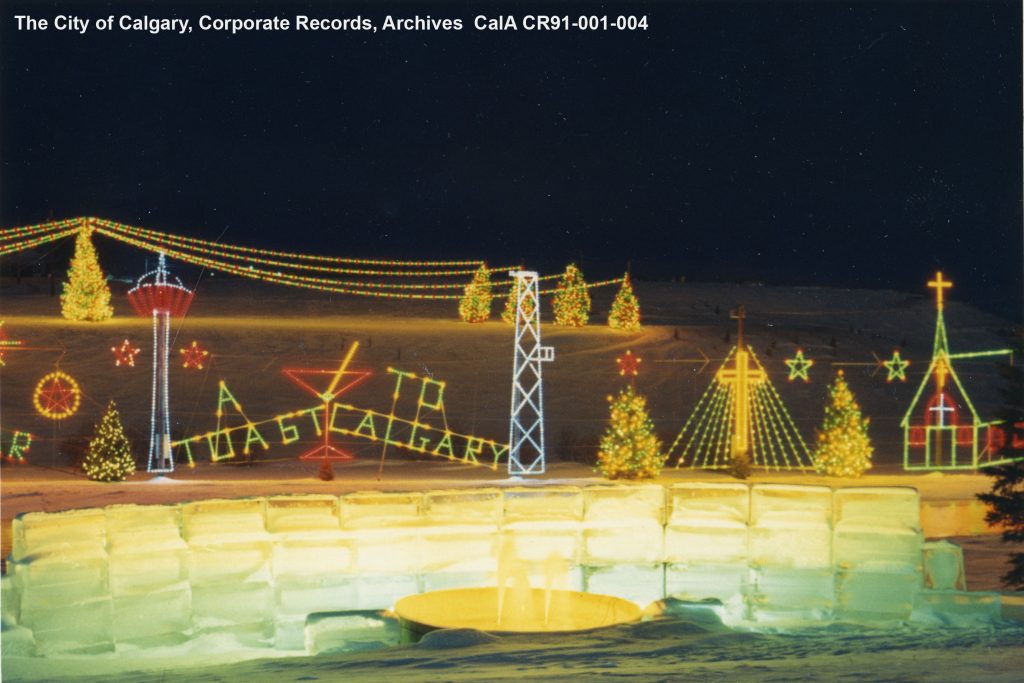

The park also contains Calgary’s first pathway as well as a beloved yearly Christmas lights display.

Suburbs

Calgary’s rapid growth from town to city, and the abundance of land surrounding the urban landscape, meant what was new could be built quickly. Sometimes this meant Calgary’s first communities experienced periods of decline.

Victoria Park represents perhaps the best example of this kind of inner city decline. After WWII, its infrastructure was aged and sometimes was not replaced on site.

The Calgary Transit Bus Barns moved to Eau Claire in 1947 and the former streetcar barn in Victoria Park burned down in 1950. The power plant in the neighbourhood was declared out-of-date in 1954, and its offices moved in 1957. Enrolment at Haultain School dropped to 135 out of a capacity of 500. The school closed in 1962 and burnt down in 1964.

Despite its proximity to downtown and the Stampede grounds, Victoria Park was over 70 years old and could not keep up with the new suburbs appearing all around the city.

One area was North Glenmore. The area was the location of a stone quarry in the early 1900s. It was established in 1957 upon its annexation to Calgary. Houses were quickly constructed followed by community and institutional buildings to serve the residents.

In 1966, St. James Catholic Church was completed. It’s not like most other churches, having been built in the Modern Expressionist style under the new guidance of the Second Vatican Council.

In the early 1960s, the Vatican opened participation in services to the congregation. In doing so, it enabled new church designs, with sanctuary offices, hall and rectory all in one building. Traditionally, these were all separate structures. Congregations were also brought closer to the altar, sometimes via circular designed buildings.

The Expressionist style is more geared toward expressing emotional content through form. This is evident in the sweeping concrete steeple and copper-clad circular opening that rise above a rigid geometric brick base. The interior is fan-shaped with 12 exposed beams, representing the 12 apostles.

Other Expressionist churches were built in Acadia, Chinook Park, University Heights, and Collingwood.

Next to the church in Collingwood is located St. Francis High School, which opened in 1962 on a farm site. My Dad, Uncle Sam, brother and I attended the school, where my Dad played on the Browns football team and won several championships. The school was supposed to be named after Bishop Francis Carroll, but he wanted it named after his favourite Saint, Francis of Assisi. Bishop Carroll High School opened in 1971, four years after his death.

The neighbourhood of Acadia was built after 1960. In 1968, St. Cecilia’s was built. It’s influenced by the Hungarian National Church in Rome, called San Stefano Rotondo, itself built in the 5th century. Its concrete dome construction is unique in Calgary.

In Chinook Park, also built after 1960, you’ll find St. Andrew’s United Church. The sanctuary of the church is an unusual sculptural form, with walls that interlock and skylights in between.

Another dramatic form was built in University Heights in 1967.

It’s another Expressionist style church, with a dramatic, projecting, curved roofline feature that is crowned at its pinnacle. This symbolizes the Virgin Mary’s crown, which is apt for Our Lady Queen of Peace Roman Catholic Church. The church served a mostly Polish congregation, who had raised the money for a new church in 1962.

In Shawnessy, a rare example of an Expressionist style home was built in 1963.

Shawnessy is near the village of Midnapore and Shaw’s ranch. It was the location of John McInnes’ homestead where his brother built a Vernacular style barn in 1915. It was refurbished in the 1970s as a community centre and is one of Calgary’s last usable barns. The area was annexed to Calgary in 1961. Major development took place in 1980 and continued into the 2000s.

The Blum Residence was designed by its owner, Gerhard Blum. It features a curved sculptural massing with four circular pods arranged in a shamrock. Its features are influenced by the rolling hills of the Foothills contrasted against the rigid Rocky Mountains. Such curved structures were possible due to advances in concrete technology, with a thin shell of concrete enabling a variety of sculptural forms.

Speaking of community centres, Bowness received a new town hall in 1956. Previously, town councils were held in various existing buildings. When it was incorporated as a town in 1952, it was time for its own building. It’s a Modern style building, which favours maximization and efficiency of space with minimal ornamentation.

Between 1946 to 1956, Bowness grew from 650 to 6000 people. Along with the new town hall, a police station, jail and library were included, very similar to Calgary’s own first town hall. It became a community service precinct in 1981 and a health centre in the 2000s.

Along with the town hall, fire departments, schools, churches and news businesses were established. In 1953, a drive-in theatre opened on Bowness Road called Cinema Park Drive. It had stalls for 1036 cars. It closed in 1976 and was replaced by Point McKay condos. In honour of Queen Elizabeth’s coronation in 1952, Bowview School was renamed Queen Elizabeth High School. Bowness was annexed to Calgary in 1964.

Residents need entertainment and by this time in history, large, indoor shopping malls replaced the outdoor promenades, such as Stephen Avenue.

Calgary’s first mall was Calgary Centre, today called North Hill Centre. It opened in 1958 on the northern edge of Hounsfield Heights/Briar Hill.

North HIll mall was originally part indoor, part outdoor. The original freestanding anchor of the mall was Simpson-Sears. This store was one of Sears’ A-class stores across Canada. Its Modernist design is seen in its square, functional shape.

When North Hill opened, it was billed as the largest shopping centre in Western Canada, with 30 stores and services in one place, including grocery store and bowling alley. In 1973, the strip mall feel was changed when the anchor stores were enclosed with the other shops into one building.

This type of design evolved for other malls too. Chinook Centre opened in 1960 as an open air complex anchored by Woodward’s department store. In 1972, Chinook merged with Southridge Mall to form one large indoor shopping complex. By 1974, Market Mall, Northland Village and Southcentre Mall were all operating.

Consumer preferences have changed over the decades, meaning malls have had to keep up.

In the mid-1990s, North Hill’s grocery store, bowling alley and theatre were demolished and replaced with more retail spaces and restaurants. I remember in 2000 when my first job as a grocery clerk at Safeway transferred to the other side of the mall, where a brand new store was constructed. In 2004, twin 8-storey condo towers were completed. This ushered in a new era for North Hill as a mixed-use residential and services hub. Other malls have since followed suit.

Institutions

The expansion of the city necessitated additions to the city’s institutions and infrastructure.

In 1952, the Junior Red Cross Children’s hospital (ca. 1922, the first children’s hospital in Canada) was moved to a new facility on Richmond Road and was renamed the Alberta Crippled Children’s Hospital. The move expanded the number of available beds from 35 to 156 beds. In 1960 it was renamed again to the Alberta Children’s Hospital.

In 1953, the fourth iteration of the Calgary General Hospital (CGH) was constructed next to the building that was CGH #3 in Bridgeland-Riverside. It was a 626-bed hospital that eventually incorporated 7 buildings, all linked, to comprise a modern, urban hospital. This is the hospital where my brother and I were born.

The completion of CGH #4 enabled patients at the isolation ward in the former CGH #2, located in Victoria Park, to move to the main hospital (referred to as Operation Measles). The CGH #2 building then served as a senior’s home, called Rundle Lodge.

CGH #4 continued expanding after its first building was completed. On 12 May 1956, the 136th anniversary of Florence Nightingale’s birth, the School of Nursing & Residence opened in Bridgeland-Riverside. About 110 nursing students housed in other wings of the hospital moved in. Calgarians donated the furniture for the common rooms, including grand piano and a collection of Ronald Gissing paintings (an English-born painter renowned for relocating to Alberta to paint Western Canadian landscapes).

In 1958, a patient received Calgary’s first artificial kidney. Also that year, two wings were opened, a north wing for radiology and administration and a south wing for the pediatric unit. CGH #4 also opened the first dental operating room in Canada. To make way for new wings, the CGH #3 building from 1910 was demolished.

A short decade later, in 1966, Foothills Hospital was built. It’s Calgary’s lead trauma centre and a research and training hospital associated with the University of Calgary. When it was built, it was North America’s largest new hospital, with 766 beds and a 166-capacity nursery.

Next to the hospital is the community of St. Andrew’s Heights. It began as a golf course located on the top of the hill, which opened in 1912 and was named after St. Andrews Links in Scotland, the “Home of Golf”.

The course closed in 1945 and the subdivision began in 1953. Chief Crowfoot School opened in 1955, which was attended by Norman Macloed, son of Col. Macleod, and Chief Joe Crowfoot, Crowfoot’s grandson.

In 1967, the Kalbfleisch Residence was built in the area, another expression of Modern style in Calgary. The architect, John Hondema, also worked for the Calgary Board of Education, while Ray Kalbfleisch was a Board administrator. Because it’s exposed to the elements up on the bluff overlooking the Bow River valley, it’s built with strong, tapered concrete walls that support a sweeping wood roof, with its living spaces recessed back.

The Girl Guides and Boy Scouts Centre was built in 1967, when the Scouts had 10,000 members and the Guides had over 5000. It served as headquarters for the movement for over 45 years.

The building was another element of the country’s centennial celebrations (860 buildings across Canada were completed), and it was built in the Expressionist style. It has a geometric structure, with sections that look like boxes stacked on top of one another. Its wooden beam, gabled roof is meant to represent a camping tent.

In 1966, Calgary finally joined Edmonton by having its very own university. The University of Alberta was founded in 1906 when its charter was passed during the first legislative session of the new province. The legislation was sponsored by Premier Alexander C. Rutherford and was modelled on the American state university system, which emphasized applied research.

The origins of Calgary’s university date to the Normal School in 1905, which trained teachers. The School was absorbed by the U of A’s Faculty of Education in 1945, becoming a satellite campus.

The idea of a separate university for Calgary was floated at this time, but it took time to find fruition. In 1957, the U of A signed a lease for one dollar with the City of Calgary for land in the northwest quadrant.

By 1960, the University of Alberta in Calgary opened its first buildings on the new campus, the Arts and Education Building (today’s Administration Building), and the Science and Engineering Building (now called Science A). The Science A building was where I took a class on international relations, and received the worst grade of my undergraduate studies in politics. I’ll never forget that lecture hall.

The MacKimmie library was built in 1963, with science buildings and residences to follow in the next decade. After some student advocacy and moves to increase the campus’ financial control, the Alberta government passed legislation to grant full autonomy to the Calgary campus, calling it the University of Calgary.

The Provincial Institute of Technology and Art (PITA) also received attention after the war. In the 1950s, the Thomas Riley and John Ware buildings were built, followed by the Crandell and Senator Burns Buildings in the 1960s. PITA was renamed the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology (SAIT) in 1960.

The Alberta College of Art (ACA) was created as part of SAIT. Art student Joni Anderson entertained students with her guitar playing. She spent one year at SAIT before moving to Toronto to pursue folk singing, becoming the one and only Joni Mitchell.

Another artist that called Calgary home for a time was W.O. Mitchell. He’s best remembered as the author of the 1947 novel Who Has Seen the Wind? and the 1961 radio show and short story collection, Jake and the Kid. Both portray life on the Canadian prairie, which was part of his upbringing in Saskatchewan.

He’s often referred to as the Mark Twain of Canada for his tales of young boys’ adventures. He was also editor of Maclean’s magazine and the director of the Banff Centre’s writing division.

In his later years, he lived in Roxboro in a 1946 Georgian Revival style home. Roxboro was prone to flooding and began experiencing development after the topography was raised to fill in an oxbow lake. Half the homes were built in the late 1920s, with building resuming after the war.

The 1946 W.O. Mitchell Residence is a stately home with copper-clad canopy, brick columns and octagonal accent window. Mitchell later added a large atrium where he grew tropical plants. A school in Silver Springs was named after him.

One more cultural institution to mention is, of course, Heritage Park. In 1963, the city donated 60 acres of land on the southwest shore of Glenmore Reservoir for a pioneer history attraction for children.

In 1964, Heritage Park opened. It’s designed as a living museum to showcase life on the prairies around the turn of the last century. Many heritage buildings and artefacts have moved to the site over the years, protecting them from demolition when they no longer had a purpose on their original site, or could not or would not be protected in situ.

One major draw is a vintage steam locomotive with cars, which was restored and operates around the Park. Another is a former streetcar from Calgary Transit, which now shuttles visitors to and from the parking lot. In 1965, a replica paddle steamer arrived, called the S.S. Moyie. The original steamer operated on Kootenay Lake, B.C. until 1957. The Park also houses Gasoline Alley Museum, which showcases an exquisite collection of antique cars and memorabilia.

Another institution preserving Calgary’s history is the Southern Alberta Pioneers’ and their Descendants (SAPD) Foundation. It held its first annual dinner in 1901. In 1923, the Old Timers as they were first known constructed Pioneer Shack on the grounds of the Stampede. The Women’s Association added a kitchen and tea room in the 1930s. In 1955, the Shack was replaced with a modern log building called Rotary House, which was dedicated to the pioneers of Southern Alberta.

For Alberta’s Golden Jubilee, a new building was constructed for the SAPD. It’s called the Southern Alberta Memorial Building and was located on a high promontory overlooking the Elbow River at Rideau Park. The building is in the Rustic style and is made with hand-hewn round logs with saddle-notch joints, which was typical of mountain architecture.

In 1967, Centennial Gate was added to the site. Its stone piers hold brass plaques bearing the names of pioneers and iron arch depicting scenes from the pioneer days.

Infrastructure

More people means more infrastructure to keep us all alive and productive.

In 1953, a new dam was built in the northwest between the city and Cochrane. It was named Bearspaw Dam after Chief Masgwaahsid (“Bear’s Paw”), one of the signatories to Treaty 7. The dam was meant to control winter flooding by stopping ice jams on the Bow River. In 1945, an ice jam on the Louise Bridge flooded 200 homes in Hillhurst. The dam also generates electricity and is a reservoir for drinking water.

In terms of transportation, the Canadian headquarters for Greyhound Lines was built in 1946 on Riverfront Ave. It was one of the few national corporate headquarters located in Calgary that was not in the energy sector. The building itself was a low brick building in the Moderne style, with Tyndall stone, rounded corners and Art Deco ornamentation. It was demolished in 2007.

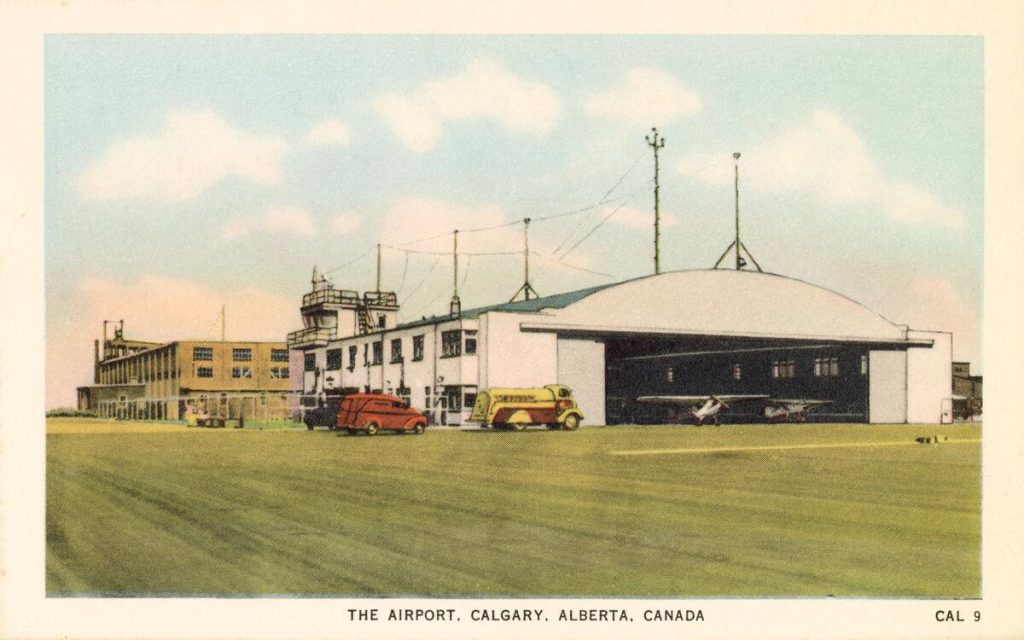

Air travel greatly expanded after the war, particularly with the arrival of jumbo jet commercial aircraft. At the end of WWII, the airport had been expanded to include four runways and more hangars and other buildings. When the air force vacated, the City resumed management of McCall Field. A hangar was repurposed as a passenger terminal and the runway was extended from 4125 feet to 6200 feet.

In 1956, a new passenger terminal was constructed based on a project from Ken Bond, a student at PITA. The building with an open public concourse and ticketing office was one of the most modern in Canada at the time. It handled 111,000 arrivals, 96,000 departures, and nearly 1 million pounds of cargo in 1957.

Calgary’s title as Oil Capital would not have been possible without international flights. The city began lobbying the federal transportation department to designate Calgary an international airport. Rather than make such a leap, Transport Canada approved a new name, Calgary International Airport, but it did not receive official international airport status until 1969.

The first non-stop transatlantic flights were scheduled by Canadian Pacific Airlines in 1961 between Calgary and Amsterdam Schiphol Airport, with more European cities added the next year.

Long haul flights needed a new runway, this time at 8000 feet and then again to the present length of 12,675 feet. The jet age needed a more sophisticated airport facility and management. In 1966, the city sold the airport to the federal government for $2 million (about $18 million today).

Besides the airport’s expansion, Calgary’s road network also underwent significant expansion due to the popularity of the automobile. Eventually, the streetcars were replaced by electric trolley buses. One of the city’s first park-and-ride’s was a bus loop in Tuxedo. The city retired its last streetcar in 1950. The Alberta government too spurred road construction, promising to finish asphalting Alberta’s three main highways (No.1, 16 and 3) by 1956.

One of the first bridges built to handle the traffic was Mewata Bridge on 14th Street. It opened in December 1954 and was meant to free up the Louise, Centre Street and Langevin Bridges and also accommodate suburban traffic, including to North Hill Centre when it opened.

It’s the best example of a Modernist style bridge, with sleek horizontality that accompanies the three elongated arches, an homage to the other two bridges downstream, and influenced by London, England’s Waterloo Bridge.

It had 5 traffic lanes, with one switching over to accommodate traffic into or out of downtown. Cloverleaf interchanges were built to accommodate traffic flow and the city introduced one way streets for the first time to more facilitate the flow. The Financial Post called it a “milestone in the city’s vast post-war development”.

If this was a milestone, the next developments were revolutionary.

The airport’s increased traffic required better road access. Edmonton Trail used to continue into the northeast after 48th Ave N. In the 1960s, the Trail was ended at 48th Ave, which had been renamed McKnight Boulevard in 1950. It’s a four lane arterial road that moves traffic east-west between North Haven, past the southern end of the airport, and to today’s Stoney Trail.

It was named for William Lidstone McKnight, a WWII flying ace in the Royal Air Force with 17 victories. He was born in Edmonton and grew up in Calgary. At medical school at the U of A, he was recruited into the air force. During the war, he provided air cover during the Battle of France and the evacuation of Allied troops. During the Battle of Britain on an offensive run over Calais, France, McKnight’s plane disappeared. His body was never recovered.

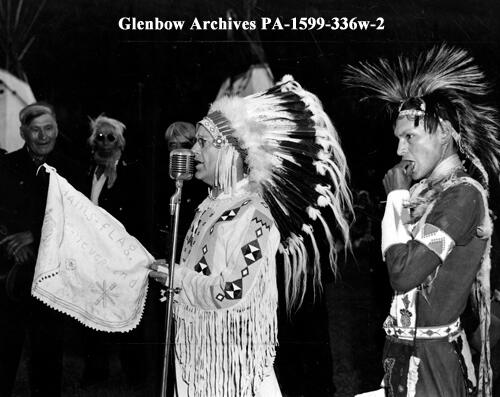

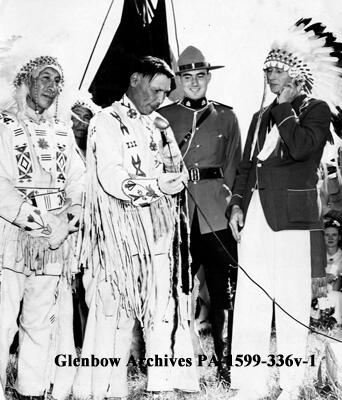

At North Haven, McKnight Boulevard turns into John Laurie Boulevard. It continues east-west past the southern end of Nose Hill Park and continues into Arbour Lake community.

It’s named after John Lee Laurie, a prominent high school teacher. He also volunteered for a decade with the Indian Association of Alberta advocating for First Nations. In 1955, he worked for the Glenbow Foundation and researched the Stoney nation. At the request of the Stoney Nakoda, Mount Yamnuska (“flat-faced mountain”) also holds the name of Mount John Laurie.

Let’s keep going with Calgary’s road system. Barlow Trail was named for WWII soldier Noel Barlow, a Welsh immigrant to Carseland, AB who served as a ground crewman to Douglas Bader, a WWII flying ace with no legs.

Barlow was part of the great evacuation from France in 1940 and went on to serve with the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan in B.C. Bader was offered by the city to name a road after him, but he turned them down and instead suggested his ground crewman Barlow receive the honour.

In South Calgary, Barlow runs from the deep south into Peigan Trail, which extends eastward. Barlow’s northern section used to run from the city limits to Blackfoot Trail, with access to the airport’s passenger terminal. It was the main route into Calgary from the north until Deerfoot Trail was built. Expansion of the airport cut Barlow off for passenger access to the airport (use Airport Trail instead).

Of course Macleod Trail has been a major route into and out of downtown Calgary toward Fort Macleod since its founding. Today it remains a major artery and commercial corridor. In 1967 it was moved out of Ramsay along 8 St SE to today’s 2nd Street. It intersects Glenbow Trail, which was built out in the 1960s over where the Elbow River leaves the Reservoir and connects Sarcee Trail in the west to Blackfoot Trail in the east.

Another road into and out of downtown is Bow Trail, named for the river it parallels. It was known as Banff Coach Road for hopefully obvious reasons. When constructed, Bow Trail was built on a more southerly route to connect downtown to Sarcee Trail. The remainder of the old road is not surprisingly called Old Banff Coach Road.

Both Sarcee and Blackfoot Trails run north-south and are named for the First Nations that are on either side of the city. Sarcee Trail was never fully connected north to south otherwise Bowness would have to be demolished.

Blackfoot Trail’s construction began in 1957 and was the original Highway 2 through Calgary. Prior to Deerfoot’s construction in the 1970s, Highway 2 then ran along 17th Ave, over the Bow River on Cushing Bridge (Calgary’s first steel beam bridge when built in 1956), and continued north on Barlow.

In 1973, Crowchild Trail was named after David Crowchild, chief of the Tsuu T’ina. When the road was named for him he said, “May this be a symbol of cutting all barriers between all peoples for all times to come.”

It was originally called Morley Trail for it connected Calgary to the mission and village. It was then paved and extended to Banff. In the 1960s, interchanges were constructed at Memorial Drive, 16th Ave NW and Bow Trail. It wasn’t until 1969 that the city purposefully planned a freeway system, of which Crowchild Trail formed an important part.

In 1961, the Trans-Canada highway was completed. It’s a 7476 km route across Canada from ocean to ocean. Between Banff and Calgary, it replaced Morley Trail (now Highway 1A) and also replaced the first crossing over the Central Canadian Rockies, the Banff-Windermere Parkway (now Highway 93). The T-Can was officially complete when it crossed Rogers Pass between Golden and Revelstoke, making it the longest uninterrupted highway in the world at the time (today that designation belongs to the Pan-American Highway, of which Alberta Highway No.2 is a part).

Calgary’s portion runs along 16th Ave N. Before it was designated Canada’s Highway No.1, the highway between Calgary and Edmonton was referred to as Highway No.1. After the T-Can, the north-south road was renamed Highway No.2.

Plenty of infrastructure ideas were floated and cancelled around this time. One of them, the Downtown Penetrator, would have bulldozed Chinatown to connect the core to Sarcee Trail. It began as an idea to move the CPR tracks away from 9th Ave S to the south shore of the Bow River. Some were appalled at the idea, and worked to protect parkland along the river, birthing what would become the Bow River Pathways.

The idea of the freeway lasted, and to it were added new bridges. But Chinatown’s residents knew how to fight for their community and the idea was axed in 1971. Instead, 4th and 5th Avenues became one-way streets.

Calgary kept growing into the 1970s, until an economic shockwave arrived, which we’ll recall next month.

Where to See this Era

Leduc-Woodbend Oilfield National Historic Site and Canadian Energy Museum, 50339 Highway 60 South, Leduc County, AB T9G 0B2

Elveden Centre, 707 7 Ave SW, Calgary, AB T2P 0Z5

Ramada Plaza, 708 8 Ave SW, Calgary, AB T2P 1H2

Calgary Tower (Husky Tower), 101 9 Ave SW, Calgary, AB T2P 1K1

Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 National Historic Site, 1055 Marginal Road, Halifax NS B3H 4P7

Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary Ukrainian Catholic Church, 704 6 St NE, Calgary, AB T2E 3Y7

Crescent Road NW, between 10 St and 3 St, Calgary, AB

Rosedale walking tour, https://myrosedale.info/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Walking-Tour.pdf

Richmond walking tour, https://www.richmondknobhill.ca/walking-tours-maps

Glenbow Museum, 130 9 Ave SE, Calgary, AB T2G 0P3

Southern Alberta Jubilee Auditorium, 1415 14 Ave NW, Calgary, AB T2N 1M4

Louse Riley Library, 1904 14 Ave NW, Calgary, AB T2N 1M5

Contemporary Calgary (formerly the Centennial Planetarium), 701 11 St SW, Calgary, AB T2P 2C4

Senator Patrick Burns Memorial Rock Garden, 1103 10 St NW, Calgary, AB T2N 1W4

Brittania Plaza, 803 49 Ave SW, Calgary, AB T2S 1G8

Mayland Shopping Centre, 817 19 St NE, Calgary, AB T2E 4X5

Sandy Beach Park, 4500 14a St SW, Calgary, AB T2T 3Y4

Confederation Park, 905 30 Ave NW, Calgary, AB T2K 0A2

North Hill Centre, 1632 14 Ave NW, Calgary, AB T2N 1M7

Foothills Medical Centre, 1403 29 St NW, Calgary, AB T2N 2T9

University of Calgary, 2500 University Dr NW, Calgary, AB T2N 1N4

Further Reading

For a deep dive into Moderne architecture in Calgary, visit https://www.calgarymodern.com/

Adriana A. Davies, From Sojourners to Citizens: Alberta’s Italian History, Guernica Editions, 2021.

CBC Calgary, “How a Calgary architectural gem went from celebrated to abandoned, graffitied and torched”

Calgary Citizen, “How the JB Barron building anchored downtown Calgary — and what’s next for the iconic structure”

What is a Skid Shack?, Canadian Energy Museum

The Leduc Era, Alberta Culture and Tourism

Calgary Herald, “Husky Tower puts Calgary on top”

Calgary Herald, “Stampede Corral: An unforgettable piece of Calgary’s history”

CBC Calgary, “That freeway once planned for downtown Calgary”

RETROactive, “Violet King Henry: trailblazing Alberta lawyer”

A History of St. Andrew’s Heights

Historic Calgary: McInnes Barn

Celebrate 110 years of Calgary Public Library by travelling into our past

Calgary Herald, “The new Glenbow museum ‘won’t be the Louvre, but it’ll be close'”

A Brief History of Jewish Life in Southern Alberta

Calgary Herald, “Italian Cultural Centre marking 70 years of rich history in Calgary”

excellent info