Welcome! The Calgary Heritage Initiative presents a series of articles throughout 2025 commemorating the 150th anniversary of the construction of Fort Calgary at the confluence of the Bow and Elbow Rivers, an important meeting place for people for millennia. Each month we’ll present one era in Calgary’s history.

Sign up to CHI’s newsletter and join us to explore the history and heritage of our region.

Oil Town

1914 to 1947

At the turn of the 20th century, Calgary was booming. The establishment of farming had led to a rush of immigration and Calgary was a key stop along Canada’s transcontinental railway, with more destinations to the north and south.

Growing City

Fort Calgary changed as the surrounding town and then city expanded. From only 4 constables present in 1880, the site was made a district post in 1882 in preparation for the arrival of the railway. Then in 1914, the railway arrived again, this time with the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway purchasing the site for $250,000 ($6.6 million today).

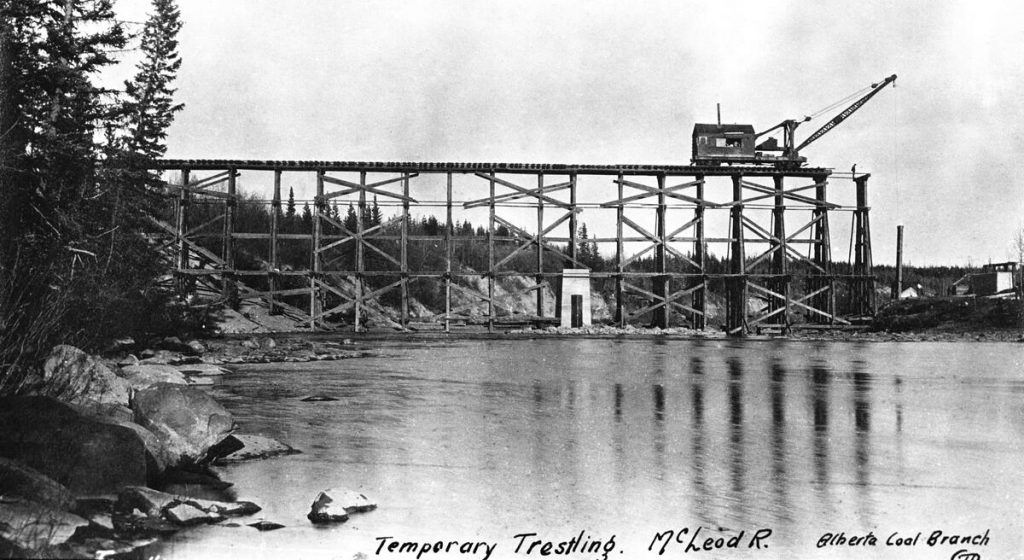

The Grand Trunk ran from Thunder Bay, ON to the Pacific coast at Prince Rupert, B.C. It went through Winnipeg and then veered northward away from the CPR line towards Saskatoon and arrived in Edmonton in 1910. This was the original route preferred by Sanford Fleming when he was surveying for the first transcontinental railway.

The Grand Trunk route then crossed the Rockies through Jasper at Yellowhead Pass and was completed in 1914. A branch to Calgary was finished the next year and Fort Calgary’s buildings were demolished to make way for a rail terminal.

The railway operated independently until it was nationalized as Canadian National Railway (CNR) in 1920. The Government intervened because the Grand Trunk ran into financial difficulties and defaulted on its construction loans.

Because of these difficulties, the Calgary terminal was never constructed, which saved the site of Fort Calgary from modern development. On 15 May 1925, the site was designated a National Historic Site.

Even though this particular development didn’t occur, Calgary did experience the construction of what we consider today to be iconic buildings. One is the Palliser Hotel.

To entice travellers, the railways constructed hotels across Canada, including in the Rocky Mountains. They were seeking to turn Canada’s natural beauty into a tourism industry.

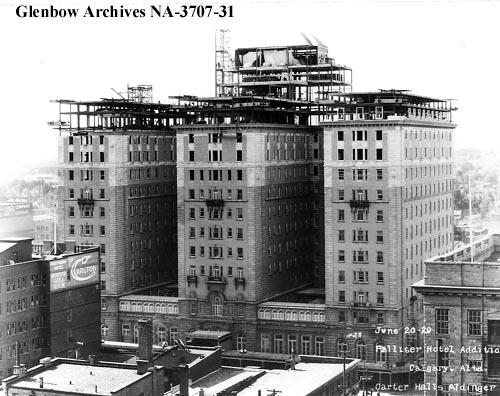

Calgary’s grand hotel was built in 1907 next to the CPR’s railway station on 9th Avenue. It featured finely cut stone and a great hall. CPR attached the hotel to the station on the location of the station’s garden and bandstand. The hotel was completed in 1914 at a cost of $1.5 million (about $40 million today).

In contrast to the Chateau style of the Banff Springs, the Palliser Hotel was built in the Chicago Commercial style, similar to New York’s Plaza Hotel. It has an E-shaped floor plan formed by three 8-storey towers, which were inspired by the grain elevators being built all across the prairies. The building has a flat roof, substantial cornices and radiating wedge-shaped stones over the round-headed windows that flank its entrance.

On its inside, visitors were dazzled with Tennessee marble floors, Botticino marble columns, oak woodwork, stained glass windows, and hand made rugs and tapestries. The Palliser was known popularly by locals as the “Castle by the Tracks”. It employed 190 people when it opened. In 1929, three more floors and a penthouse were added, making it the tallest building in Calgary at the time.

The hotel was instantly popular and a centre of Calgary’s social scene for decades. The Kings Arm Tavern was a colourful spot for locals and travellers, and was known by Calgary’s gay men in the 1930s as “The Pitt”. It was also Calgary’s last men-only club. After it was renovated and reopened in July 1970, its first woman employee set fire to the “Men Only” door signs.

Famous guests at the Palliser over the decades have included future Prime Minister R.B. Bennett, the Prince of Wales (who later abdicated the throne), King George VI, Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Cary Grant, Sophia Loren, Mikhail Gorbachev, and explorer Roald Amundsen, the first person to reach both the North and South Poles and the first to navigate the Northwest Passage.

The hotel provided vital employment to many locals, including my grandmother, who washed dishes upon arriving in Canada from Italy in 1958. It also was a first job for my father and some of his mates, who attended school during the day and waited on the in-crowd at night.

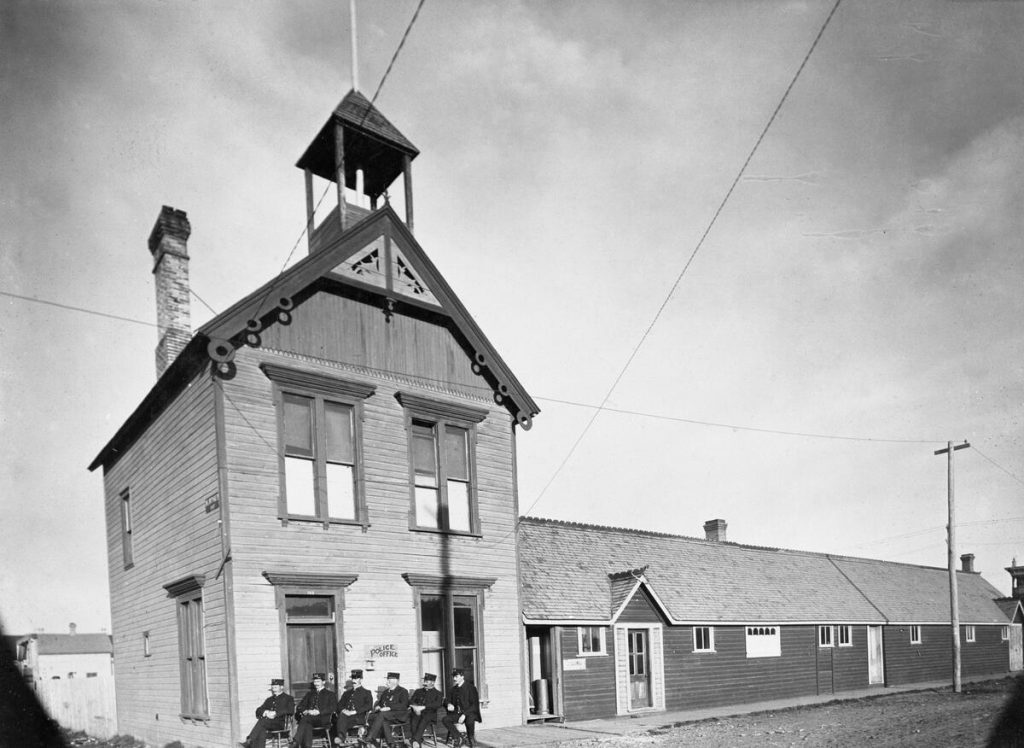

Calgary also received a splendid civic building in 1911, which reflected the growing prominence and bright future of the city. The land for the original city hall was donated by a private citizen in 1885, the tenth anniversary of the establishment of Fort Calgary and the year after Calgary was incorporated as a town.

In 1904, City Council tried to buy some land for a new city hall, but the purchase failed when put to a plebiscite. Council then went back to the site of the wood-framed town hall and police office and decided to demolish it for a larger and grander building.

Architect William M. Dodd was brought in to design the new hall since he was known for his work on Regina’s City Hall (demolished in 1965). He had previously designed Alexandra School in Inglewood.

Construction of the steel framework and Paskapoo sandstone exterior began in 1907, but it was fraught with problems. In 1909, another plebiscite denied additional funds for the project, so work stopped for almost a year. The total cost was double the expected budget, topping out at $300,000 (approx. $8 million today).

The Richardsonian Romanesque Revival style building has a symmetrical form with elevated main floor and single clock tower. It was designated a National Historic Site in 1984 as the only surviving example of the civic halls built in prairie cities at the turn of the last century, and is also the last one of its kind constructed in Western Canada.

Another public building in Calgary is Heritage Hall at the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology. It was completed in 1922 and designated a National Historic Site in 1987.

The 3-storey steel and concrete building with red brick and sandstone was designed in the Collegiate Gothic style, with twin square towers, parapets and distinctive windows. It’s the only one of its kind in Calgary.

The building housed the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art (PITA) and the Normal School.

PITA was founded in 1916 to address the need for a skilled workforce, with Alberta the first province in Western Canada to launch a public post-secondary education institute. It also helped retrain veterans after WWI. The institute had been housed temporarily in Col. James Walker School. The Alberta Normal School was a college for training teachers. An art school was added in 1929 and the first aeronautical engineering courses in Canada began in 1934.

Calgary had earlier become the home of another college, founded in 1910. United Church Reverend George Kerby sought to set up a school to benefit young people from rural areas. He wanted to name it Calgary College, but the name was being reserved for a new university. He chose at the last minute the name of Calgary’s tony neighbourhood, Mount Royal. The college became affiliated with the University of Alberta in 1931 so it could offer undergraduate courses.

Today, the Kerby Memorial Building is the last remaining building from the historic campus of Mount Royal College. It was built in 1948 as a new addition to the campus and named after the school’s founder. In 1966, MRC severed its connection to the United Church of Canada and became a public institution, moving in 1972 to its present-day Lincoln Park campus. The Kerby Building became the Kerby Centre for senior citizens.

One last iconic building to mention is Hudson’s Bay Company’s new department store. Completed in 1913, it’s a 6-storey steel and concrete frame with a terra-cotta cladding in the Chicago Commercial style. It’s also wrapped by an intricate arcade of granite columns and arches, similar to the ones along the Rue de Rivoli in Paris. It’s thought to be the only one of its kind in North America.

In the 1910s, HBC was facing an entirely different economy in Western Canada, with retail trade now more significant than fur or land sales. To remain relevant, HBC embarked on a construction program, building 6 department stores across the west.

The first of these new stores opened in Calgary and the last was in Winnipeg in 1926. The store was Calgary’s largest for some decades thanks to expansions in 1929 and 1956. The 6th floor dining room with Elizabethan furnishing was one of the most attractive in the city and helped anchor the store as a destination for Calgarians.

Calgary’s growth was also evident in its residential expansion.

The Nose Creek valley was crossed with plans to develop Albert Park. Albert Smyth and his business partner promoted a new subdivision in 1908. With sales of plots lagging over the next 4 years, they designed a scam to lure buyers. They laid railway ties to the village of Forest Lawn and spread the rumour that a streetcar was being built. The scam was quickly revealed and the ties were instead used for firewood. The scammers skipped town. Albert Park developed sporadically over the next several decades and was annexed by Calgary in 1960.

City Beautification

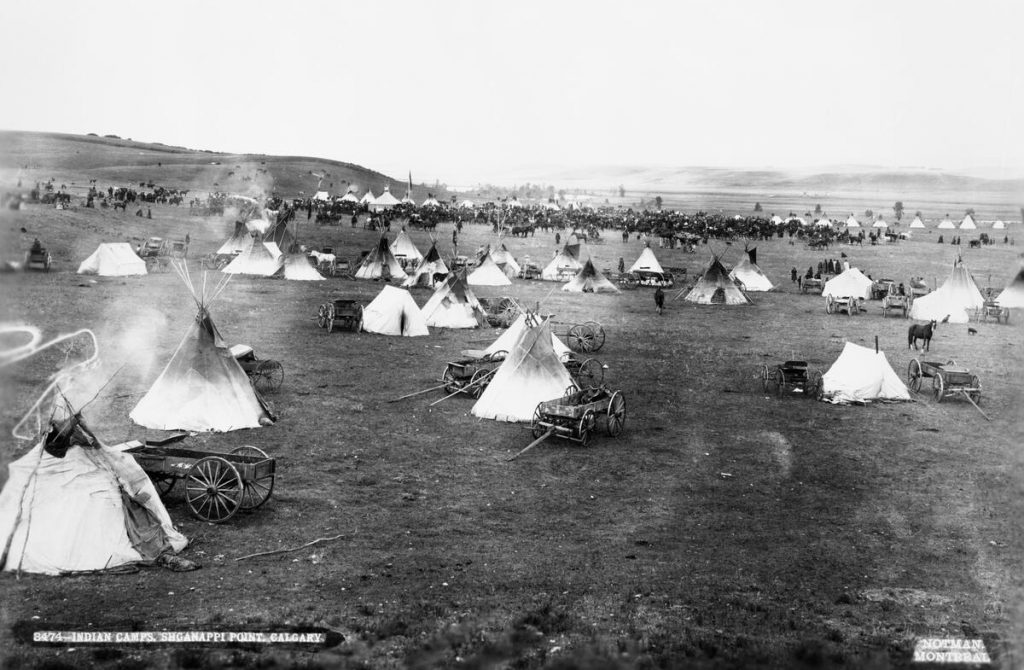

The city annexed more land on its western border in 1910, including Shaganappi. This is a Cree word meaning “rawhide lacing”.

The area was an Indigenous gathering place and the site of early Métis settlements. The hilltop was chosen by William Pearce as the location of Calgary’s first cemetery in 1885 (it closed in 1890 and the burials were transferred to Union Cemetery). It was a park until 1914, when Parks Superintendent William Reader proposed a golf course to increase use of the park as well as streetcar revenue.

Calgary’s first municipal course and its second oldest opened at Shaganappi Point in 1915. It’s an example of a Parkland style golf course and is known for its natural setting and panoramic views. The cost of a tee off was 25 cents (about $6.50 today). Bunkers and pot-hole features were added in 1917.

As the park was developing, so was the area then called West Calgary. Around two dozen homes were built in 1915 some years after a group of local farmers, ranchers and businessmen registered the subdivision. One member of the group, Charles Jackson, had started Calgary’s first milk delivery service. John S. Henry from PEI retired from farming to West Calgary and built Henry Residence, a Queen Anne Revival style home with a unique brick veneer.

Superintendent Reader made a mark all around Calgary. Born in Britain, Reader started out as the gardener for Pat Burns and was a founder of the Calgary Horticultural Society. At the time, members were influenced by the City Beautiful movement.

The movement started in the United States as a response to crowded cities, and it went on to shape urban planning across North America. The design of the National Mall in Washington, D.C. was one result of the movement.

In Canada, the designs were more muted but nonetheless the movement influenced local horticultural groups and their ideas about parks, city landscaping, gardening and recreation.

Reader was hired by the city as Superintendent of Parks, Cemeteries & Recreation in 1913. For the next 30 years, Calgary became his garden, with the city even providing a cottage for him and his family near Union Cemetery. He planted over 4500 kinds of plants and wrote about his gardening and experimenting in the Calgary Herald.

Today you can visit his personal legacy at Reader Rock Garden. Reader tested many alpine plant species for their adaptation to Calgary’s climate and laid out an Arts and Crafts style rockery. It was open to the public and offered inspiration and lessons to others.

After his death, the garden fell into disrepair and his cottage was demolished. Up to 95% of the plants were lost and the greenhouses were removed. Renovations begun in 2004 have helped to restore the garden. Today it is a municipal, provincial and national historic site.

Reader also left a legacy for all Calgarians to enjoy. He began skating and swimming on Calgary’s rivers and the Bowness lagoon. Elbow Park Pool and Gardens became Calgary’s first municipal swimming facility in 1914. In 1922 was built a dressing room structure, the only one of its kind left in the city.

Reader also advanced recreation opportunities with playgrounds, tennis courts and new parks, one of the first being Riley Park. He planted today’s historic boulevards with elm trees, poplars, willows, lilacs, honeysuckle and dogwood to foster civic pride and make the former bald prairie bloom.

At springtime, take a stroll down Garden Crescent SW, Calgary’s first historically designated streetscape, or along 5A Street SW in Cliff Bungalow to see the green ash trees. Hillhurst has lilac meridians along 11 St, 6 Ave, and Bowness Road NW. And Bridgeland has 8 St NE with its canopy of Elm trees.

Reader was also part of the Vacant Lot Gardens Club. In 1914, Calgary’s building boom had come to an end. Vacant lots blighted the city, filling with weeds and debris. The city began purchasing some of these for community gardens and beautification. They were also important resources of affordable food, especially for the working classes, who otherwise were left with expensive and poor quality imported supplies.

The Club was supported by Annie Gale, the first woman city councillor in the British Empire. She argued for self-sufficiency and also helped inaugurate a municipal market in Calgary. By 1937, 1900 members grew over $70,000 worth of produce.

These plots became Victory Gardens during WWII to support the war effort. You can still visit the last of these gardens in Bridgeland-Riverside, at the Vacant Lot Gardens municipal historic site.

Last but not least, Reader helped establish the Calgary Zoo on St. George’s Island. The island was Calgary’s first park owing to its location next to downtown. It was a place for picnics and socializing.

A collection of animals was brought to the park in 1917. A travelling animal show arrived in Calgary in 1922 and gifted a young mule deer to the City, which was housed on the island. These animals started drawing big crowds and generating revenue.

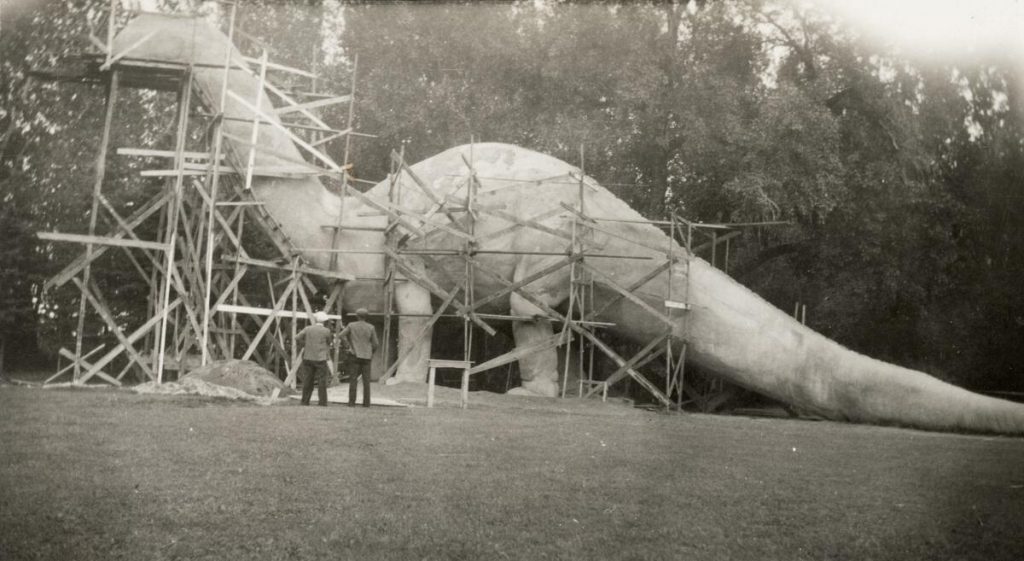

Dr. Omer Patrick from Ontario was interested in city beautification and became the founding president of the Calgary Zoological Society in 1928. In 1935, the Zoo expanded by including a natural history park, complete with concrete dinosaur sculptures. The only surviving sculpture is Dinny the Dinosaur, a provincial historic resource.

The boomtimes lasted until the start of the Great War in 1914. We’ll look at the war years next month, and continue now with the emergence of Alberta’s energy industry.

Energy Demand

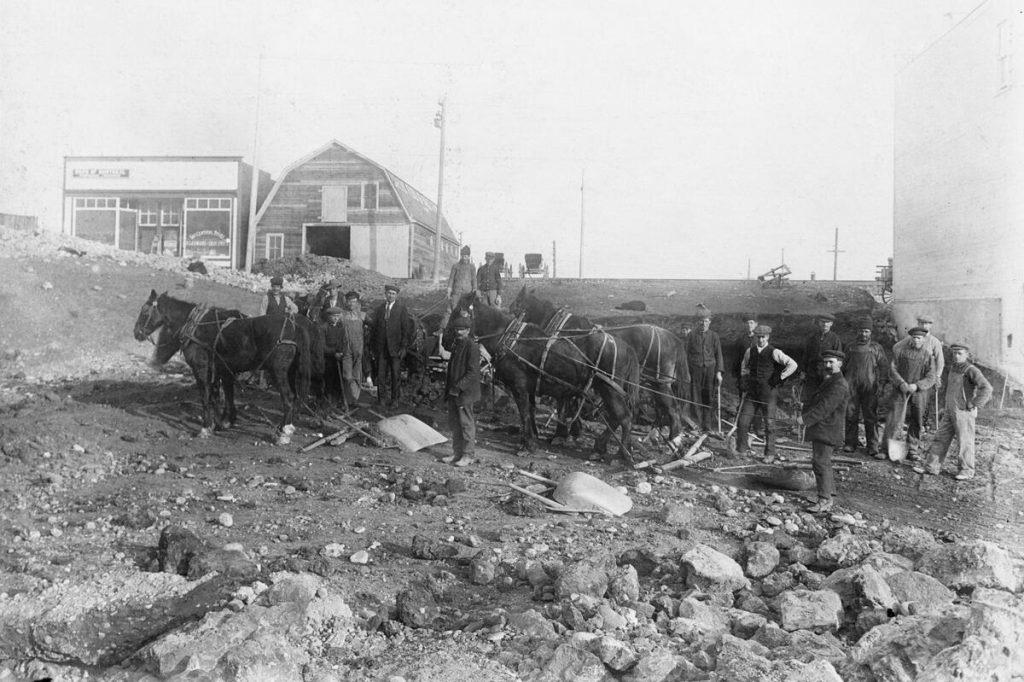

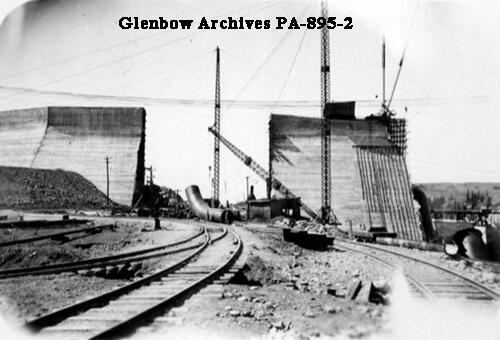

Calgary’s rapid growth required a corresponding increase in energy supply. Horseshoe Dam was built in 1911 to provide electricity to Calgary. It was supposed to be ready by 1909, but engineering complications, floods and accidents delayed it.

One year later, Lake Minnewanka Dam was built to partially regulate the seasonal flows and provide consistent water for hydroelectric generation. Plans were drawn up for additional dams, but their location within Rocky Mountain (later Banff) National Park led to significant opposition.

After WWI’s economic downturn, electricity consumption again surged and new power plants were needed. In 1929, Ghost River Dam and Reservoir was completed on land leased from Stoney Nakoda First Nation where the Ghost River reaches the Bow. The project doubled electricity production and high voltage lines were built to supply Edmonton. The Bow River watershed was powering the province.

But let’s face it, Alberta doesn’t have the hydroelectric resources of Ontario or Quebec, which have powered the development of their industries. It would take different kinds of energy to anchor Calgary and Alberta’s economic growth.

Coal

In our January article on Prehistory, we saw that the formation of fossil fuels over millions of years was a geographic blessing for Alberta.

As the Rocky Mountains formed, layers of rock were pushed upwards, including seams of coal. These are dark brown or black bands in the layers of rock. It’s estimated that 90% of Canada’s usable coal resources are contained in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin, a massive area stretching from NWT to southern B.C., Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Some of these coal seams are visible to passersby. To the Siksika and Kainai, the banks of the Oldman River are known as Sik-ooh-kotoki (“place of the black rocks”). In 1793, Peter Fidler reported a seam of coal along the Red Deer River that he used to produce heat.

The first commercial coal mine in Alberta opened on the west bank of the Oldman River in 1874 thanks to investment by New York City entrepreneur Nicholas Sheran. He was a whisky trader who was looking for gold but found coal instead, which he sold to traders at Fort Whoop-Up and shipped to Fort Benton, MT via bull train. The mine stayed open until his death in 1882.

Also in 1882, Sir Alexander Galt, one of the Fathers of Confederation, and his son Elliot, a government commissioner in southern Alberta, formed the North Western Coal and Navigation Company. The largest shareholder and president of the company was William Lethbridge.

The company opened a number of mines near Coalbanks, which was renamed Lethbridge in 1885. Because of these operations, the CPR built a line from Lethbridge through the Crowsnest Pass in 1898 to ship coal across the continent. Towns developed along this line, including Coaldale, Coalhurst and Black Diamond, AB.

Mines in the area followed. In 1903, McGillivrary mines fueled a boom in the Pass with their mine and processing plant at Coleman. The townsite was laid out to service the mine and received its name from the maiden name of the mine president’s mother. This made Coleman a “company town”, one of the features of early 20th-century development across North America. Much of Coleman’s downtown and existing mine buildings comprise a National Historic Site.

The town quickly surpassed nearby Blairmore in size to become the largest in the Pass. Blairmore started as a CPR siding and was settled mainly as a lumber town prior to supporting the local coal mining industry. It became the principal town in the Pass following the decline of Frank, AB.

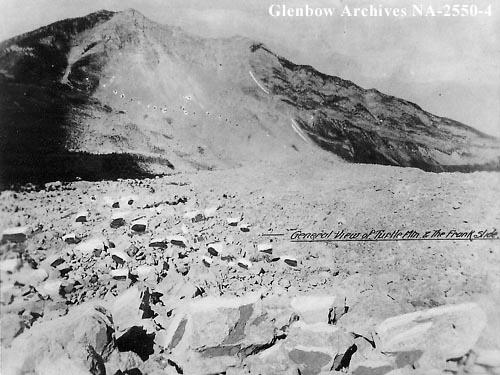

Frank was founded in 1901 by Americans Sam Gebo and Henry Frank, who developed coal mining at the base of Turtle Mountain. It was the first incorporated village in the Pass and its grand opening was attended by NWT Premier Haultain and federal minister Clifford Sifton. Two years later, on 29 April 1903, the Frank Slide destroyed the mine, rail tracks, several rural businesses and seven houses on the outskirts of town.

The Frank Slide was a massive rockslide that occurred at 4:10 am when an estimated 110 million tonnes of limestone slid down the mountain. Between 70 and 90 people were believed to have died in the rockslide, the deadliest in Canadian history. Because of the incredible amount of rock involved, the area remains a burial site.

The Rocky Mountains were formed by the slow uplift of rock over millions of years. The result is that some areas are more stable than others, with Turtle Mountain being known for its relative instability. Indeed, Indigenous peoples in the area, the Blackfoot and Ktunaxa, called it “the mountain that moves”. Even now, if you are walking in the Rockies on a quiet, clear day, you may hear cracks or booms as the mountains continue to shift.

Coal mining and its reverberations may have compounded the mountain’s instability. A wet winter and then a sudden cold snap that froze water and expanded cracks on the night of the disaster may also have been a factor.

Even though the mine eventually reopened and further development took place, the government feared another massive slide. It ordered the closure of the southern portion of the town in 1911. The town further declined when the coal mine closed in 1917.

The slide area was designated a provincial historic resource 1977 and an interpretive centre opened in 1985. The centre is also home to the Geological Survey’s monitoring system, which uses a sensor network to chart the movements of the mountain’s peak.

As for the rest of the Pass, mining’s decline throughout the area in the middle of the 20th century led to the amalgamation of the towns into the Municipality of Crowsnest Pass.

Before moving on, my own family has ties to the Blairmore area. My great-grandfather, Salvatore Imbrogno, was a coal miner in the Greenhill mine. He journeyed to Canada to find work and better his family’s life. This led my grandfather and grandmother to arrive in Alberta also in search of better opportunities compared to what was available in rural southern Italy.

Coal mining is dangerous however. Salvatore died in 1945 in an accident in the mine when he was trapped between coal cars and a building. Between 1900 and 1945, more than 1000 men died in the mines of the Crowsnest Pass.

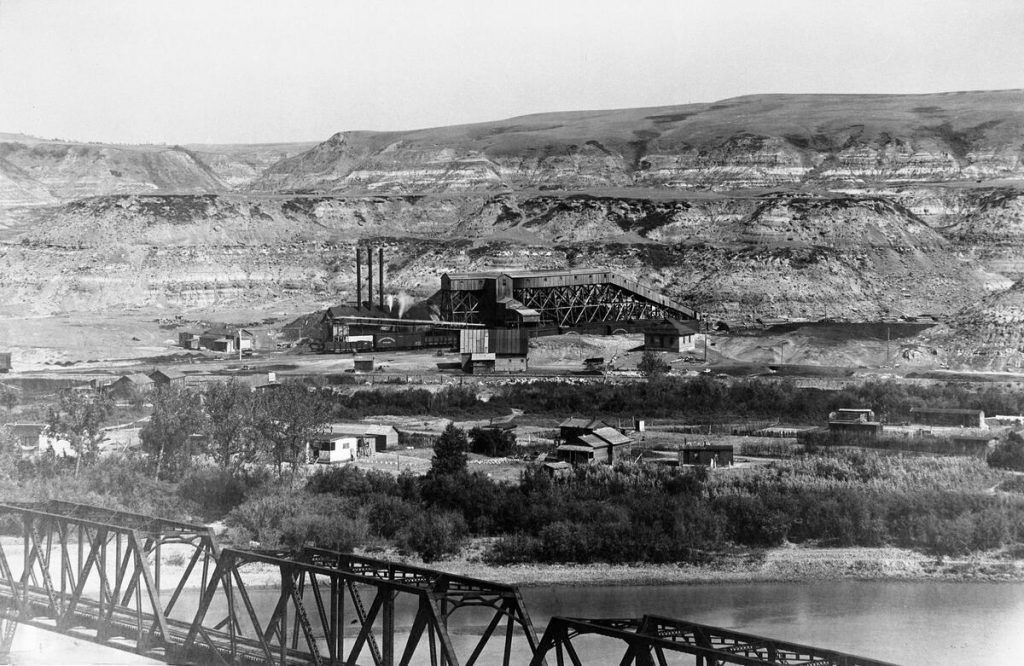

Coal mining occurred elsewhere in Alberta. Near Rocky Mountain House, Brazeau Collieries was established in 1909 by Martin Nordegg in partnership with CNR, which was looking for shipments on their line through Jasper.

The site started mining operations in 1911 and by 1913 the town of Nordegg had sprung up. The company went bankrupt in 1955. Restoration efforts by locals created a provincial and national historic site, with the site being one of the most complete examples of a coal-mining surface plant.

On Halloween day 1941, an explosion of flammable coal dust occurred at the mine, killing 29 men. An inquiry determined that gas testing did not occur prior to using explosives on the coal seams, contrary to the safety provisions in the Mines Act.

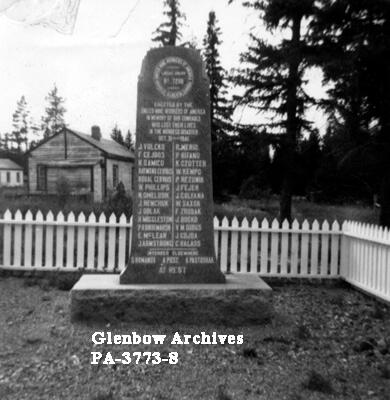

After the explosion’s fumes had cleared, fellow miners rushed to the rescue and brought out 30 workers. The mine was largely undamaged except for a cave in at the explosion site. A monument was erected dedicated to the workers who perished.

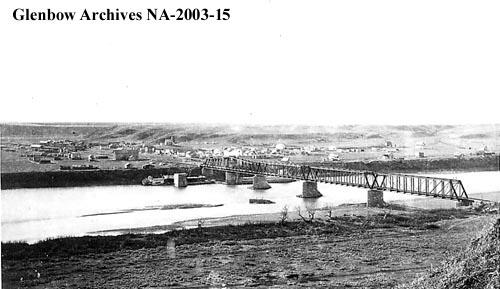

Elsewhere, Samuel Drumheller was hiking in the Red Deer River valley to examine potential ranchland, but instead came across coal seams. He purchased the land and started mining at several sites around today’s townsite. A post office was established in 1911 and the town’s name was determined by a coin flip between Drumheller and an area homesteader, Thomas Greentree.

The settlement grew rapidly and became a village in 1913, a town 3 years later, and then a city by 1930. The last coal mine in the area, Atlas, is today a National Historic Site that preserves Canada’s last wooden tipple (a coal sorting structure).

Of course Drumheller is also famous for dinosaur bones (see January’s article). For some decades, geologists and scientists dispatched to Western Canada to survey and explore had reported fossil sightings, with Joseph Tyrrell first reporting a dinosaur fossil in the Red Deer River valley in 1884. Yet this did not garner much attention outside the scientific realm.

Homesteaders and ranchers, particularly in the Drumheller area, started reporting that it was strewn with bones. When rancher John L. Wegener told this to Henry Osborn, curator of New York City’s Museum of Natural History, the Great Canadian Dinosaur Rush began, lasting about a decade from 1910.

Americans arrived to scour the banks of the Red Deer River for bones, which moved the Canadian government to hire Charles H. Sternberg, a private fossil hunter, to collect specimens for retention in Canada.

Today’s Dinosaur Provincial Park was the site of much of the action, which remained civil owing to the sheer amount of bones available for digging. Hundreds of fossils were uncovered during this time and are now displayed in museums throughout the world.

Oil and Gas

Other fossil fuels to make their mark on Calgary and area were crude oil and natural gas.

Natural gas was first recorded in Alberta in 1883 at a CPR siding, near today’s Medicine Hat. The CPR was in fact drilling for water to power its steam-driven locomotives. When it struck gas, the drilling rig was destroyed by fire from the unexpected flow. The Geological Survey of Canada noted that the rock formation here was common throughout Western Canada, and so predicted that natural gas would be found often.

What was once a tent city became a town, the first in Alberta to have natural gas service. The name of the city was chosen from the Blackfoot word Saamis (“medicine man’s hat”). Legend has it a Cree medicine man lost his headdress in the South Saskatchewan River during a battle with the Blackfoot.

Other small gas finds occurred elsewhere in Alberta. In 1908, Major Walker and Archibald Dingman struck gas east of Calgary, which was used for home fuel and street lighting.

Then Eugene Coste discovered gas at Bow Island in 1909. With a 275-km pipeline, the wells began servicing Calgary in 1912 and were the beginning of the Canadian Western Natural Gas Company (today’s ATCO Gas). This made Coste the father of natural gas in Canada.

With sufficient supply, the Calgary Brewing and Malting Co. became the first commercial user of natural gas in Western Canada. It continued to operate even during Prohibition in Alberta (1916-1924) by selling soft drinks for domestic consumption and shipping its beer elsewhere. During the Great Depression, it kept employees working with projects such as its gardens and fish pond, including the famous buffalo statue on its grounds. It closed its operations in 1994.

Meanwhile, exploration continued for oil wells. First Nations in the area of today’s Waterton Lakes National Park used oil seeps on the ground as medicinal salves. John George “Kootenai” Brown, a trader and scout in the area, began harvesting the oil for lubricant and lamp fuel. Other seepages were found, which were reported in the press.

John Lineham organized drilling in the area to reach the source of the seepages. A small well of thick crude oil was open for about a year until cave-ins forced its closure. Today it has the designation as First Oil Well in Western Canada National Historic Site.

Kootenai Brown began to worry about development in the area and petitioned the government to expand the forestry reserve around the lakes. He was a ranger in the park between 1910-1916.

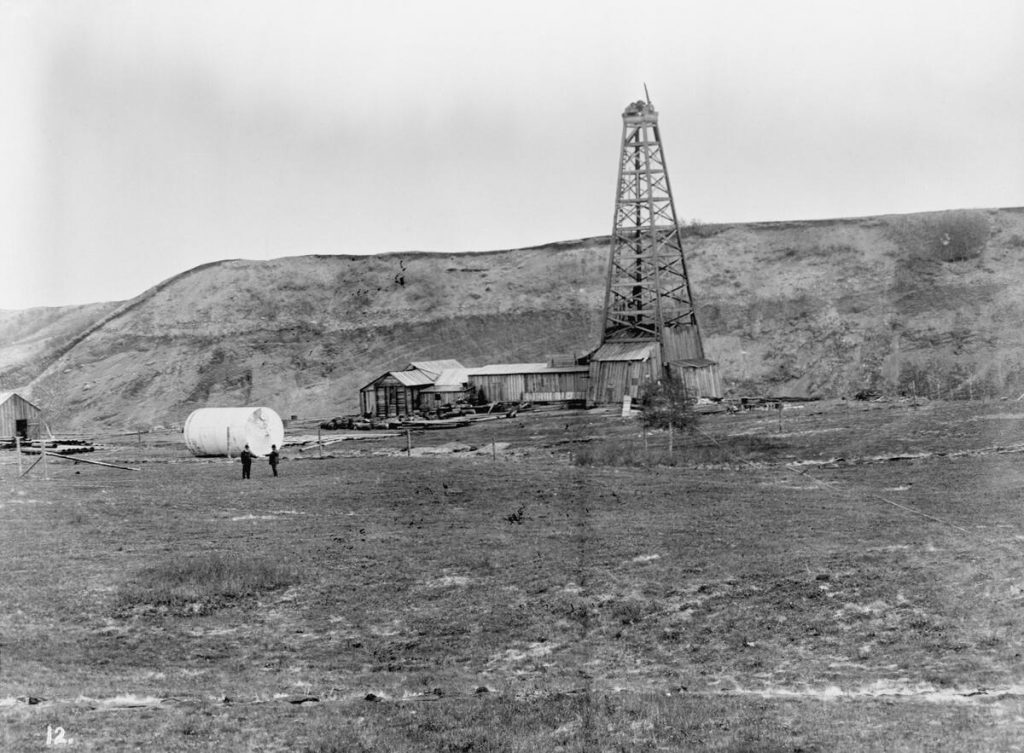

At Turner Valley, it was believed the area contained significant reserves owing to similarities with Pennsylvania’s oil fields. William S. Herron was hauling coal and noticed gas seepages along the Sheep River. He went on to form Calgary Petroleum Company with Archibald Dingman and William Elder.

The company drilled three wells starting in 1913. The next year, on May 14th, a significant reserve was struck at Dingman No.1 well, a “wet” natural gas product that looks like gasoline rather than crude oil.

Herron is today known as the father of Alberta’s petroleum industry. He also helped start Calgary’s tradition of gifting a white hat to visitors when he wore one at the 1947 Calgary Stampede.

The find generated considerable excitement and led to a rush in oil exploration. Over 500 companies formed within days in the hopes of finding and establishing more wells, though some of these were scams and others based on wild speculation. Herald writer Torchy Anderson wrote that “a lively but fairly sane cow town became a madhouse”.

To control the feverish trading, the Calgary Stock Exchange was established. It built the Stock Exchange Building by October. However, because the Dingman find was not crude oil, the fever broke. The CSE had to renegotiate its construction debts with Sir Lougheed and eventually closed in 1917, remaining dormant until 1926.

Investment did continue despite the relatively small volumes from the wells that did produce gas. Calgary’s first oil refinery opened in 1923 and Imperial Oil from Ontario purchased Calgary Petroleum Co. This acquisition ended an era of entrepreneurial oil and gas development.

Drilling continued around Turner Valley and Black Diamond, with another significant strike made in 1924.

Calgary Petroleum Co. had become Royalite Oil, a division of Imperial Oil. The Royalite No.4 well blew in with a huge fire that burned uncontrolled for almost a month. To stop it, well control experts from Oklahoma used dynamite to blow away the fire and then used steam to keep the well from lighting again. This find established Turner Valley as Canada’s first major oil field.

Crude oil was finally discovered in the area in 1936 after hundreds more wells were drilled. It was discovered in the deepest well dug so far in Alberta, and was recognized soon after as the largest oil field in the British Empire. Because of its size, it drew workers from Oklahoma and Texas. By 1942, production peaked at 10 million barrels because sufficient supply was needed for the war effort.

Overall, all these discoveries occurring so close to Calgary sealed its fate as an Oil Town.

Calgary and its environs has always been memorable for me since I arrived there in late winter of 1952 for service with PPCLI at Currie Barracks in South Calgary. Although I’ve travelled a good part of the world, the centre of my mental universe is 8th Avenue Calgary where I met my future wife in a little spot called the Pig ‘N Whistle Coffee shop, in April 1954. Articles like yours always has me rereading events that I’ve known about and loved of the Alberta of the past. Nordegg mine disaster was one of them that I had almost forgotten as one of my Army colleagues Father had been killed in that disaster. I look forward to future articles.

We’re very happy to hear you’re enjoying our articles. Thank you.

Construction on the Palliser Hotel began in 1911 (not 1907) and it was expanded by 4 floors in 1929 on top of the original 8. The article has good info. not normally covered in publications. Thank you.