Olympic City

1988 – Present Day

We’ve arrived at the last era in our tour of Calgary’s history. For our purposes, the Olympic City era will cover Calgary to the present day. Next month, we’ll examine heritage as an issue in Calgary, and take a peak at what new era may be emerging before us right now.

Winning Bid

The lead up to the 15th Winter Olympiad in Calgary spans a few decades prior to the opening ceremonies, held on 13 February 1988 at McMahon Stadium. It would be the first time Canada and Alberta hosted a winter Olympics games.

Calgary had previously bid three times to host the Winter Games, and Canada as a whole tried six other times. The first was for Montreal in 1956, but it lost to Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy, north of Venice. Vancouver tried two bids, losing to Denver on the first and withdrawing the second.

Calgary’s first bid was for the 1964 games, but it lost out to Innsbruck, Austria. It tired again in 1968, but Grenoble, France won by 3 votes. Then it tried once again in 1972 with Banff, but Sapporo, Japan won the day.

With the third try not being lucky, Calgary’s Winter Olympic dreams seemed out of reach. But a group of enterprising individuals revived the Calgary Olympic Development Association (CODA) in 1978 to give it another shot.

Frank King and Bob Niven were both involved in the oil patch and were members of Calgary’s Booster Club, an organization that supports local athletics. They thought the city was ready to host the Olympics.

The Canadian Olympic Association agreed in 1979, and so the race was on to win the rights to host the 1988 Olympic Winter Games.

Calgary’s fourth attempt pulled no punches. The cost was estimated to be $217 million ($836 million today) due to the construction of all new venues.

The reasons were twofold: 1) to grow Canada’s ability to train future athletes at state-of-the-art facilities, and 2) the prior host cities’ winter facilities were aging, not to mention they were smaller. As the millennia approached, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) was seeking newer, larger venues to host bigger crowds at Olympic Games, with TV and advertising rights to boot.

Backing the bid was the Heritage Savings Trust Fund. Throughout this series, we’ve seen the booms commodities can cause, and we’ve also seen the slow downs and busts. The Heritage Fund was created in 1976 with the goals of saving for the future, strengthening and diversifying the economy, and improving the quality of life of Albertans.

Despite the expense, CODA had a two-pronged approach to securing support. First, all three levels of government committed to the project. Canada put in $200M and Alberta pledged $70M, with $53M additional if needed. Mayor Ralph Klein demonstrated his famous politicking skills by meeting with IOC delegates to sell Calgary.

Second, CODA went about building local support for the games. It sold $5 memberships to Calgarians, with 80,000 contributing to the cause. It helped too that the Calgary Flames NHL team had arrived just after CODA re-launched. Plans for a new stadium were being drawn up, both for the team and for the Olympics. A new, spectacular centrepiece could therefore help showcase Calgary’s bid (and it provided plenty of seats for tickets sales too).

At the bid presentation, the cost for Calgary’s bid topped $331 million, with $84 million in reserve. The biggest cost was for a new 18,000 seat arena, dubbed the “Olympic Coliseum”. Preliminary competitions for hockey and figure skating would be hosted at the Stampede Corral and Max Bell Arena. $15 million was projected for a new speed skating track, the Olympic Oval at the University. Ski jumping, bobsleigh and luge would take place at Bragg Creek along with cross-country and biathlon. Spray Lakes above Canmore would receive a new $13 million alpine centre, and the University would host the athletes’ village.

As you may already know, some of these plans were altered over the years leading up to the Games. But before all that, Calgary had to win the bid.

To make sure it did, changes were made, and CODA laid it on thick. It committed to subsidizing travel for European athletes, who would have to endure grueling travel to the middle-of-nowhere North America for the games rather than take a quick jaunt to their local ski village. CODA also showcased Calgary’s modernity, mountain landscapes, and western hospitality and culture, including provided tours for IOC delegates.

It all came down to Calgary versus Falun, Sweden and Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy. The delegations arrived in Baden-Baden, West Germany for the IOC’s vote. Cortina never released its budget for the games, and Falun planned to host skiing events 400 km away from the city.

Calgary won in the second round of voting, by 17 votes.

Preparation

When Calgary’s win was announced, the city cheered. An airplane flew around town with a banner that read “Thank you CODA”.

The delegation tossed their white hats in the air at the announcement. Its members celebrated with champagne at nearby CFB Baden–Soellingen, a Cold War-era Canadian facility. Mayor Klein said he would run for reelection.

When back at home, the bid had to be turned into a plan and then executed successfully. CODA became the Calgary Olympic Committee (COC ‘88) and was headed by Bill Pratt, a former general contractor who was involved in Chinook Mall, the Stampede Grandstand and McMahon Stadium. He was also a volunteer and then general manager with the Stampede.

His was the exact experience needed to start building, on time and on budget, which is what happened more or less, though his managerial style was not always appreciated. There was also a scandal involving tickets, with over 50% going to the IOC rather than 10%. The result was high demand for tickets by Calgarians, along with many disappointments (the luge tickets were all my Dad could get) and swift backlash.

Mayor Klein had to threaten an inquiry to get COC to loosen up its control of the planning. One result was opening room for over 9000 volunteers to have more duties. More seats were added to the Saddledome, capacity was increased at several venues, and the closing ceremonies were moved from the Saddledome to McMahon Stadium, which had 2x the capacity. In all, 80% of tickets were allocated to Calgarians.

The bid had promised new facilities and Calgary was ready to build after its worst economic slump in 40 years. In last month’s article we saw the construction of the Flames’ home ice, which was christened the Olympic Saddledome in 1983.

The next major venue was the Olympic Oval, which sits next to the University of Calgary.

It was the first covered speed skating venue in North America, the only other being built in Salt Lake City, UT. It’s one of the fastest ice surfaces in the world, with over 300 world records being set there. Its climate controls are one reason why it’s fast, Calgary’s high altitude is another.

From its opening to 2019, the Oval produced 32 Canadian Olympic medalists, including Catriona Le May Doan and Ted-Jan Bloemen. Today, the Oval is showing its age and its future may be in doubt.

By the mid-1980s, one of the venues was at risk. I’m pretty sure my very first memory ever is my father taking me to see the luge run at Canada Olympic Park (COP). But I don’t remember going to Bragg Creek. What happened?

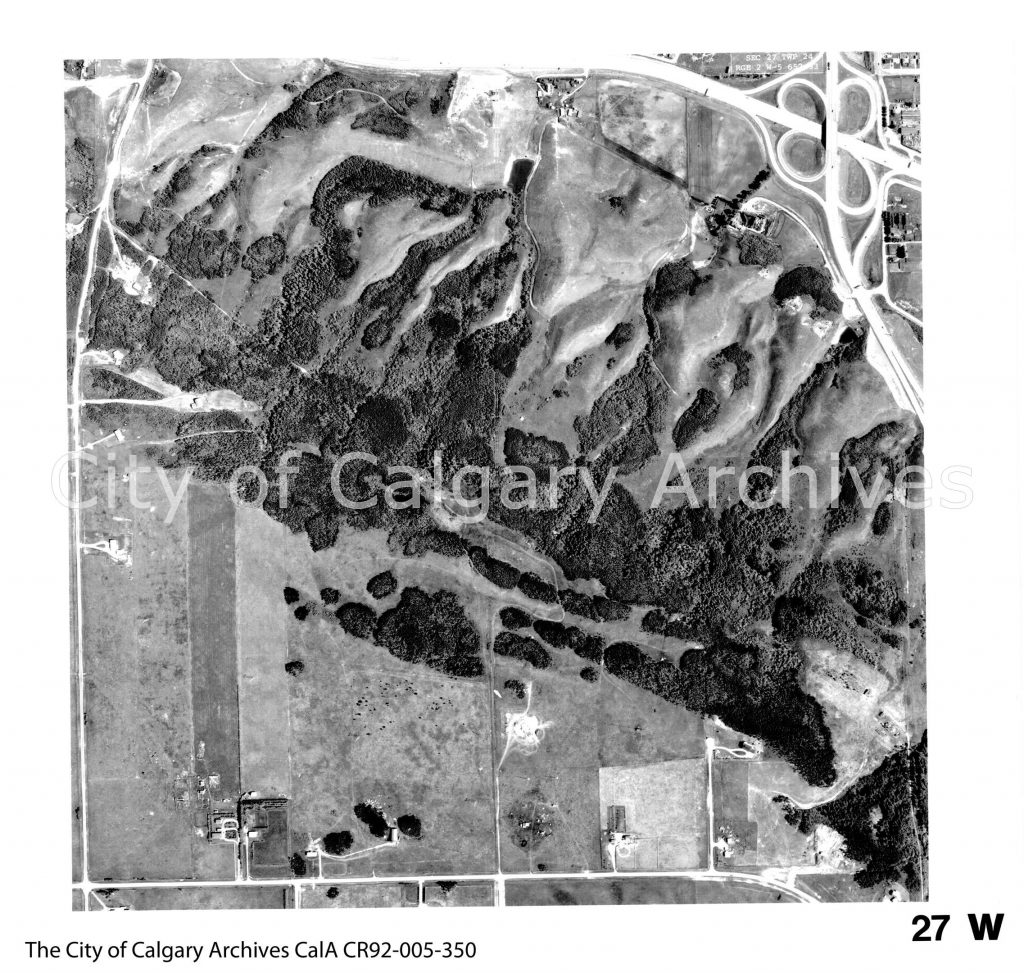

Well, locals were opposed to the scale of development. So instead, COP was conceived and built on Paskapoo Slopes.

The area is similar to Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump as it was used to kill and process buffalo herds. Sites dating back 8500 years ago have been identified. The area is composed of six forested benches that were formed by glacial lakes. Select areas towards Sarcee Trail have been preserved for future parkland.

In 1960, part of the slope was developed into a ski hill by Norwegian members of the UofA ski team. Snow making technology was in its infancy but it solved the problem of Calgary’s more moderate winter (the chinooks are a Godsend though).

By 1981, Paskapoo Ski Area included a Go-Kart track and driving range and it hosted the World Cup Freestyle Event. When the Olympic venues planned for Bragg Creek needed a new home, Paskapoo was ready. COP became the venue for bobsleigh, luge, freestyle skiing and ski jumping.

Today, COP sits next to Cougar Ridge community to the south, Patterson Heights to the east and Crestmont and Valley Ridge to the west.

Patterson was annexed in 1956 and built out in the 1980s. It was originally composed of residential acreages. On its eastern edge is Broadcast Hill, the home to CFCN’s radio and television facility since 1961. The Olympic’s Media Village was hosted by the community.

While parts of its northern end are preserved for parkland, extensive development was allowed at Trinity Hills on Medicine Hill despite the Save the Slopes effort by residents to create a regional park. Besides the Blackfoot name for the hill, several roads use Blackfoot words, such as Na’a (“Mother Earth”) Drive and Piita (“eagle”) Rise.

Coach Hill to the south is the southern extent of the Paskapoo Slopes. It was developed in 1979 and was named after Old Banff Coach Road, which runs through the area.

Extensive residential construction has also occurred on the other sides of COP. Cougar Ridge and West Springs were annexed in 1995 and built out in 2001. Extensive archaeological studies were completed before the installation of water and sewer infrastructure.

Crestmont was built in 2003 and continued to completion in 2024. About 30% of the area has been set aside to protect aspen forest and creek beds. The rest is homes, since no retail or commercial areas were included in this secluded area that boasts no traffic lights between it and Banff. A new community to the west was approved in April 2025, to be called West View.

Valley Ridge and its golf course occupies the former site of Happy Valley Campground. It closed in the 1980s but the economic downturn meant the area did not develop until a decade later.

Today, COP is both a winter and summer playground in the city. It hosts downhill skiing, snowboarding, a halfpipe, cross-country skiing as well as mountain biking and zip-lining. It relies on man made snow to create the proper terrain, mostly due to Calgary’s inconsistent weather conditions, thanks mostly due to chinooks.

In 2008, COP was chosen to host Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame. It opened for Canada Day in 2011. The hall of fame took inductees starting in 1955. It shared space with the Hockey Hall of Fame in Toronto until 1993. The building’s exterior was designed to mimic the elevated platform that athletes ascend to receive their medals, with its red and white colours taken from our national flag.

Today, the entire COP site is called the Canadian Winter Sport Institute, or WinSport. The entire facility hosts one million visitors per year. Its mandate remains the training and development of Olympic athletes and to keep Calgary’s 1988 Olympic legacy.

Another venue for the Olympics was the Canmore Nordic Centre. It hosted cross-country skiing, biathlon and other nordic events. Today, it’s part of a provincial park at the foot of Mount Rundle. Its extensive trails are used for cross-country skiing, mountain biking and hiking. There’s even a disc golf course, which might be an event at the 2028 Olympics in Los Angeles.

Canmore’s Olympic investment revived the local economy. In 1979, the local coal mine ceased operations. The town slumped, which wasn’t helped by the overall economic situation in Alberta. Then, it was announced that Canmore would host some of the events for the Olympic Games. Construction began on infrastructure and tourism facilities, the start of Canmore’s journey to today’s mountain playground.

The last venue to mention is Nakiska. It’s located on Mount Allan and was built specifically to host alpine ski events, including freestyle moguls. Other mountains in Kananaskis were investigated but Mt. Allan is close to Calgary, already had access roads, and could be used by the public after the Olympics. However, the Federation Internationale du Ski had major concerns with the runs and major changes were ordered.

The name Nakiska comes from the Cree word for “meeting place”. It opened in 1986 in preparation for the Olympics and hosted World Cup events. Today it’s a private ski hill and is also the training ground for Canada’s alpine ski team.

“Faster, Higher, Stronger”

Suffice it to say, Calgary’s hosting of the Olympic Games was a resounding, fantastic success. It was the first to make use of a veritable army of volunteers, which galvanized locals. It made money and its facilities became iconic and important aspects of the city’s infrastructure and Canada’s athletic training network (rather than falling into disrepair and becoming entries in various photographic exhibitions on modern Olympic ruins).

And let’s not forget, it was FUN!

To commemorate the Olympics’ ancient heritage, an Olympic torch is lit at Olympia, Greece to launch the torch relay. Each relay ends at the opening ceremonies, where it’s used to light a cauldron that burns throughout the games. It’s become a symbol of peace and competitive spirit.

Calgary’s torch relay arrived in St. John’s, NFLD from Greece 3 months before the opening ceremonies. For 88 days, the torch travelled across every province and territory, covering over 18,000 kms, the greatest distance ever for a torch relay until Sydney 2000.

The torch is shaped as a mini-version of the Calgary Tower. It’s made of maple wood, aluminum and steel, all collected in Canada, and weighs 1.7 kg (3.75 pounds). It was fueled by a mix of gasoline, kerosene and alcohol to ensure continuous burning in Canada’s unpredictable and cold winter.

Also completed for the Olympics was the Saamis Tepee, the tallest in the world. After the Olympics, a Medicine Hat entrepreneur purchased the 800 tonne, 215 foot tall sculpture. Today it marks the site of the Saamis Archeological Site and Tourism Visitor Centre where was once located a buffalo camp and meat processing site.

With preparations complete, the Olympics arrived in Calgary on a Saturday in February.

For the next 15 days (a first for the Winter Olympics), the city was showcased to the world. And that itself has had a lasting impact. Throughout my travels, whether in Europe, the USA or Australia, people I spoke to knew about Calgary because of the Olympics.

Calgary’s Winter Games had a record 57 countries participating, comprising 1424 athletes.

One of the more unusual attendees was Jamaica. Their bobsled team’s attempt to compete is immortalized in the 1993 movie Cool Runnings, starring the late, great John Candy. They competed in the 4-man and 2-man races, with their sled crashing on the third run, resulting in a last place finish. Of course, they were first in the hearts of the spectators for having finished the run by walking the rest of the way alongside their bobsleigh.

One more “triumph of effort” from Calgary 1988 was also made into a movie in 2016. Eddie the Eagle tells the story of the British ski jumper who placed last overall. He was so bad, the Olympics implemented the Eddie the Eagle rule, which requires competitors to take part in international events prior to an Olympics.

At an event marking the 20th anniversary of the games in 2008, both Eddie and a member of the Jamaican bobsled team rode the zipline at COP. Eddie also led a procession of skiers down the slopes with an Olympic torch in hand. It just goes to show, even if you fail, it’s the attempt that matters.

Calgary’s was also the last Olympics to be attended by the Soviet Union and East Germany, since major political changes were just around the corner in those countries.

The Opening Ceremonies were held at McMahon Stadium. The show made use of volunteers to perform country-western dancing, who were found by scouring western bars in the city. 1.5 billion people around the world watched.

As well, audience members were each given a coloured poncho to wear to make for stunning overhead visuals (but only after prison inmates ripped out the Coca-Cola patches on them, due to Olympic sponsorship rules). As the Olympic cauldron was lit, the RCAF Snowbirds flew overhead with coloured smoke representing the five colours of the Olympic rings. The Calgary Tower was also lit up with a natural-gas fueled flame.

And guess what? Calgary’s weather did not cooperate. The opening ceremonies were held in about -9 with a brisk wind.

Over the course of the next 15 days, temperatures ranged from -28 to 22 °C. For the first few days, freezing temperatures forced the cancellation of 8 outdoor competitions. Then chinook winds topping 160 km/hr forced the cancellation of downhill skiing at Nakiska and ski jumping at COP. Several days later, bobsleigh and luge were postponed due to high temperatures interfering with the cooling system. Good thing that, for the first time in Olympics history, tickets for events that were canceled could be refunded. It was also the first time that alpine events were held on artificial snow.

In terms of medal count, we can count the European way (number of gold medals) or the American way (total number of all medals). Either way, the Soviet Union was No.1. Their team won a combined 29 medals, 11 of which were gold. East Germany and Switzerland came in second and third, respectively.

Canada failed to win a gold medal on home soil, coming in 13th place with 2 silver and 3 bronze . Despite the failure, the effort by many Olympians was duly noted and cheered by Canadians.

Canada’s silver medals were in figure skating. Brian Orser and Elizabeth Manley became local heroes. Brian battled his American competition, Brian Boitano, in what was dubbed the “Battle of the Brians” (Boitano won gold by 1/10 of a point).

Manley skated the best performance of her career, which interrupted the “Battle of the Carmens”, between American Debi Thomas and East German Katarina Witt, both of whom elected to skate to a song titled Carmen. Manley was also a fraction away from winning (this can be the problem with sports competitions that are judged rather than timed).

Olympic Plaza was the venue for medal ceremonies. It was built to bring the games closer to locals and visitors, borrowed from the Sarajevo winter games. A public square had been identified in downtown redevelopment plans from the 1970s and thus the Plaza essentially completed the revitalization project. It contained a stage, gardens and wading pool that was the city’s only refrigerated outdoor ice rink in wintertime.

It was built with bricks that had the names of donors carved into them, which 22,000 Calgarians purchased for $19.88 in 1987. The plaza went on to be used for New Year’s Eve and Canada Day celebrations as well as all kinds of festivals.

It was also home to the Famous Five statue, unveiled in 1999. The Famous Five were a group of Albertan women who took a case to Canada’s highest court in 1929 to determine whether the word “persons” in Canada’s constitution included women. In the now-famous Persons Case, the court sided with the group, and the journey toward equality took a leap forward. A copy of the statue now sits on Parliament Hill in Ottawa.

The Plaza is currently undergoing revitalization work and the construction of a new auditorium. Originally, the bricks were going to be destroyed but public outcry convinced officials to save them and return as many as possible to Calgarians.

The outcry occurred, in my humble opinion, because of the personal investment by thousands of Calgarians in the Olympics Games. Indeed, one triumph of this time was the participation of Calgarians. This was our games!

After 80,000 Calgarisn purchased memberships to get the bid off the ground, a total of 22,000 people signed up for 9400 volunteer positions. All kinds of tasks were needed, from helping spectators to picking up garbage. Calgary already had a practice at mobilizing volunteers because of the Stampede, with the Olympics expanding the city’s spirit of western hospitality and community dedication.

The official mascots were also imbued with the city’s western roots. Hidy and Howdy were smiling polar bears dressed in cowboy attire, with their names chosen through a public contest. A team of 150 students from Bishop Carroll High School made up to 300 appearances per month leading up the games. The mascots became iconic and they graced the entry signs to the city on the major highways for two decades. They were even painted on the gym walls of my elementary school.

These Olympics also hosted several demonstration events, including curling, freestyle skiing and short track skating. No official medals were awarded for these events, but in a harbinger of things to come, Canada won gold in speed skating.

The Closing Ceremonies were held on 28 February at McMahon Stadium, the first closing ceremony for a Winter Olympic Games. Of the 60,000 attendees, 10,000 volunteers were granted free admission as thanks for their dedication and work. The Olympic flag was lowered and Mayor Klein handed it back to the IOC, who then passed it to the next host city of the winter games, Albertville, France. Calgary’s time in the international spotlight was over, but truly, this was just the beginning.

At the end of the day, the 1988 Winter Olympic Games cost $829 million (about $2 billion today). They were the most expensive games ever held up to that point, which offered a lesson in what happens when so many venues are built from scratch.

There were public improvements that went along with the venues. We saw Olympic Plaza next to Arts Commons. There were also upgrades to the Trans-Canada Highway between the University and COP, the extension of the LRT system to the University, more bike paths, and two new residence halls as the UofC (a model for athletes’ villages that was copied for Atlanta 1996 and Salt Lake City 2002) . Canmore too received many upgrades, including a new hospital, fire station, swimming pool and curling rink.

The games were an economic boost, with $450 million generated in salaries and wages, and almost $1 billion in economic activity for Alberta.

The Olympics owes Calgary a great debt as well. Prior to 1988, the winter games were considered second-rate compared to the summer games, to the point that the IOC was considering eliminating them altogether. Yet CODA convinced the IOC it not only could generate revenue from the games but also a legacy that would improve winter sports. Calgary’s games also experimented with several games familiar to many Canadians that are now part of the Olympic sports roster, most especially curing.

For these Olympic Games then, we could use the word investment, since every venue has been used successfully afterwards, in part thanks to endowments set up from the games’ surplus. Calgary is estimated to have hosted over 200 competitions in the 20 years following the games.

The games also helped Canada achieve enormous success in winter games competitions. The medal success Canada experienced at Vancouver 2010 with so many gold medals would not have been possible without Calgary 1988.

You’re welcome, Canada.

Lord Stanley’s Cup

We left off with the Flames’ playoff run during the 1987-88, which they lost to Edmonton.

The next season, the Flames won their second Presidents’ Trophy with a franchise record 117 points. Doug Gilmour was acquired on the roster and the Flames entered the playoffs by taking Vancouver in seven. Mike Vernon saved the day during that series and went on to win against the Los Angeles Kings in four straight games. Next up was Chicago, which the Flames took in five games.

Their playoff run set up a rematch of the 1986 Stanley Cup finals, which the Flames had lost to Montreal. They took it to six games and on 25 May 1989, Calgary won its first ever Stanley Cup. Lanny McDonald retired right after this, and just shortly after scoring his 500th goal, which had given the Flames the lead in the final game.

It was also the only time a winning team defeated the Canadiens to win the Cup at the Montreal Forum. The win also meant that Sonia Scurfield, wife of Ralph, became the first Canadian woman to have her name engraved on the Cup. And so far, it’s also the last finals to be contested between two Canadian teams (ouch!).

The Flames struggled to stay competitive over the ensuing 30-odd years.

The Flames were one of the first NHL teams to receive a player from the Soviet Union in the 1989-90 season. Sergei Makarov went on to win the Calder Memorial Trophy as NHL Rookie of the Year. It was a controversial choice because he was in his 30s, so the NHL changed the rules to limit nominees for the award to a maximum age of 26.

The Flames made the playoffs that year, which they did not see again until 1996. They did not win a playoff series until 2004. It was one of the longest playoff droughts in NHL history.

So when the Flames did win during the playoffs, the city was overjoyed.

The Flames’ run was the beginning of the Red Mile, a section of 17th Ave S stretching westward from the Stampede Grounds at Victoria Park C-Train Station. Crowds gathered in the bars to watch the game and paraded down the street to celebrate win after win.

When the Flames won game seven against Vancouver off an overtime goal from Martin Gelinas, tens of thousands spontaneously swarmed the street, shutting it down to traffic. 10,000 people were present for that first series win in 15 years, which grew to over 55,000 when the Flames played the Tampa Bay Lightning in the final round. For the duration of the playoff run, 17th Ave became a “C of Red” and the social place to be seen (or, like me, others watched at home with friends and family).

The Red Mile evoked memories when Flames fans jammed Electric Avenue (11 Ave SW) in the 1980s during playoff runs and Olympic celebrations. It was also the epicentre of Calgary’s nightlife, with Coconut Joe’s and other bars lining the street. The avenue was eventually disbanded by the city out of fear of low drink prices leading to a concentration of drinking and assorted behaviours. A drive-by shooting that rendered future MLA Kent Hehr bound to a wheelchair and other violence helped seal the fate of the avenue.

What else is there to say about that playoff run, except this: THE PUCK WAS IN THE NET! (more on the controversy here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iORumLN7K0Q )

Team Captain Jarome Iginla, Assistant Captains Craig Conroy and Robyn Regehr, wingers Chris Clark, Shean Donovan, Martin Gellinas, Chuck Kobasew, Oleg Saprykin and Chris Simon, defenseman Mike Commodore, Andrew Ference, Jordan Leopold and Steve Montador, and goalie Mikka Kiprusoff were household names and hometown heroes.

They had defeated the Western Conference’s top three seeded teams, Vancouver, Detroit and San Jose, to reach the finals, the first time a Canadian team made the Stanley Cup series since 1994.

Although the Flames did not win the Cup, the impact on Calgary was tremendous. And now a new generation awaits a fantastical run to the Stanley Cup.

Iginla would go on to become the all-time scoring leader for the Flames, surpassing the prior record set by Theoren Fleury. He left the team in 2013 for Pittsburgh, retired from hockey in 2018, and was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2020.

Earl Grey’s Cup

The Flames lack of success in the 1990s was the opposite of the tremendous success of the Calgary Stampeders CFL team.

Wally Buono took over as head coach and the team went private when Larry Ryckman purchased it. The success of the team was led by quarterback Doug Flutie, Jeff Garcia and Dave Dickenson, receivers Allen Pitts, Terry Vaughn and Dave Sapunjis, with defencemen Alondra Johnson, Stu Laird and Will Johnson. Their 13 year record was 153-79-2, reaching the Grey Cup six times and winning in 1992, 1998 and 2001.

It was a great time to be a Stamps fan!

Controversy did follow however. The team changed ownership after Ryckman was fined for stock manipulation. It was purchased by Michael Feterik, who put his son on as QB. Wally Buono then left for BC after the 2002 season, and the Stamps went through 3 coaches in 3 years. Grey Cup success didn’t return until 2008, the Stamps’ sixth trophy.

The Stamps appeared in the 100th Grey Cup Game in Toronto in 2012. I was there in the city, and watched the festivities at a bar surrounded by Argos fans. The Stamps lost, but the Torontonians were nice about it. I did get to see 2 CF-18 Hornet fighter jets perform a fly past between the downtown skyscrapers.

The Stamps won again in 2014 and 2018, with Bo Levi Mitchell winning Most Outstanding Player at the 2018 awards. Another interesting fact I have about the Stamps is that Bo Levi is from Katy, TX, where I lived for a time during the 1990s when my Dad’s job moved down south.

More Sports

Let’s round out Calgary’s sporting heritage.

The Calgary Hitmen is a junior ice hockey team currently playing in the Western Hockey League. The team is named after founding co-owner Bret “The Hitman” Hart, a member of the Hart wrestling family.

The team was founded in 1994 and qualified for the playoffs for 13 consecutive years between 1998 and 2010. In 1999, they were the first Calgary team to play for the Memorial Cup since 1926 (they lost to the Ottawa 67’s). They won a second championship in 2010 but lost the Memorial Cup to the Brandon Wheat Kings. Their popularity with Calgarians means the team regularly hits over 10,000 fans per game.

In the world of baseball, Calgary has had several lower league teams. The team that competed in the highest leagues was the Calgary Cannons, who played between 1985 and 2002 in the Triple A Pacific Coast League. The Calgary Vipers tried to carry on baseball in the city but they were not financially sustainable.

Baseball in Calgary was played at Foothills Stadium, a 6000 seat facility that is being demolished as I write this.

Unfortunately, they never won a title. But the city did see over 400 players who went on to play in the MLB, including Alex Rodriguez (“A-Rod”). Also unfortunately, Foothills Stadium (ca.1966) was showing its age and was one reason why the team moved to Albuquerque. A new multi-sport fieldhouse will replace the structure.

Calgary entered the world of North American soccer (“footy”) in 2018.

Cavalry Football Club plays in the Canadian Premier League at ATCO Field, located on the grounds of Spruce Meadows. It won its first CPL championship in 2024, earning a berth in the 2025 CONCACAF Champions Cup, which is a competition amongst North American, Caribbean and Central American soccer clubs.

A new 12,000 seat stadium is slated for future construction.

Leave a Reply